Kenneth Tooley Schubert - Four Months in Belgium

Evading Capture

The squadron was taken off the German targets and was detailed to rail busting after the Essen trip. By bombing rail targets in Belgium and France, we would help to isolate the beaches of Normandy for the invasion. The crews that flew the aircraft on alternate nights to us had a bad experience; 71 officers and men didn’t return from that trip. We got 13 new aircraft and hit St. Ghislain and then Haine St. Pierre in Belgium on the night of May 8, 1944. The trip to Haine St. Pierre was our eighth operational trip. We bombed the target from 2,000 feet to ensure absolute accuracy because the rail yards were in the centre of the city. We were then supposed to come home in industrial haze. We came out at 2,000 feet alright, but there was no haze, only a beautiful full moon lighting everything up like day.

A FW-190 (German fighter) attacked us and, when we went into our evasive action, we found that another Halifax was below us, so we had to break off the evasive action or collide with him. That was the chance the German was looking for. He came in from behind and raked our aircraft with cannon fire. He came around a second time and raked us again, knocking out our two port engines and starting fires in the fuselage. Our pilot gave the order to jump – by this time we were down to 1,000 feet. Al, Butch and I were supposed to leave the aircraft by the lower exit door under the flight engineer. Butch delayed while looking for a fire extinguisher, but then we were out. All of the crew got out except for Bill Wilson, the pilot. It appeared that he was trying to hold the aircraft steady to give the rest of us a chance to get clear. The aircraft was out of control and he was killed in the crash. That was a loss of one very fine young fellow.

After I had cleared the aircraft, I could see it peel off and dive into the ground. I could also see the other five parachutes spread out behind me. As I tried to adjust my descent, the uncertainty of my immediate future brought a prayer of thanksgiving from me for being able to get clear of the aircraft and of hope that I would survive what ever lay waiting below me and that I would be able to make it home to my family and son.

As I descended into the darkness and neared the ground, I could see a village and several groups of trees. I landed in a field behind a house and the chute snagged on one of the trees that lined the field. When I released the parachute, I fell and twisted my ankle – I was otherwise unharmed. On landing, I lost track of direction and had no idea where the rest of the crew were. This was a blessing in disguise as they were all captured except for the wireless air gunner, Al Casey, who eventually contacted the underground about 20 miles from where I had landed. I gathered my parachute and Mae West together and was burying them as we had been instructed when I heard movement. I hid behind a tree and waited. I saw a man in a white night dress coming toward me. As he got closer, he tried to communicate and indicated that he was not a Bosch. I assumed that he was friendly by his actions and his dress and, as he indicated that I should follow him, I gathered up the chute and he led me across the open field. We finally got to the edge of the field and to his home. He and his family were really excited, and I guess by now I was in a state of shock at the rapid change in my situation.

In this home, the family consisted of the father, mother, two daughters and a son – there was another daughter working away from home. They sent the older daughter to get a neighbor who could speak English. When they arrived, they turned out to be an elderly couple who had spent some time in the tobacco fields in Ontario years before and their English was very limited. They explained that the man I was with, Emiel Duyck, had been in the Belgian Army when it had surrendered, and the Germans had promised that all of the soldiers would be sent home. They had been, for a short time, when the Gestapo appeared in the village and had conscripted them all for forced labour on the railways (which we had been busy bombing). Emiel had been badly treated on the forced labour crew and soon became sick, so was once again sent home. When he had recovered from his illness, the Germans again grabbed him and sent him off to the railway where he was forced to work for several months before he got home again. He was very bitter toward the Germans. The neighbours were very nervous having me near them in the village, and wanted me to leave right away. Emiel, however, would have none of this and insisted that I stay until he could find out what the Germans were up to. By this time, it was morning and the family was thinking of breakfast.

The breakfast consisted of fried potatoes and bacon with black bread and coffee. The potatoes were long past their prime, the bacon was moldy and still had the bristles on it, and the bread was black and gooey and stuck to the teeth like glue. My stomach wasn’t quite ready for this fare but, within a few days, this food looked and tasted like it was fit for a king and I waited for it to be served. The children had all suffered with large boils from the lack of a proper diet. The boy had one large boil on his tongue and had nearly died before I got there. This was on May 9th, so the crops were not up in the fields yet and the food supply was practically exhausted.

In the first few days, I stayed in the attic of the house. I had my parachute with me, so I spent my time unstitching the whole thing. The panels of nylon were stuffed into pillows and later were used for wedding dresses for the girls. Emiel had gone to the farm where the aircraft had crashed and reported that there was very little of it or the pilot left. He also found out that four airmen had been taken prisoner and one of them, Butch MacStocker (the navigator) had a broken ankle; the rest had been unharmed. The Gestapo was searching the village for the other two members of the crew (me and Al Casey). The next day there was a loud banging on the door and much excited talking down below. A search was made of the house, but not the attic – so I was very lucky again. If I had been found, the family would most likely have been shot for harboring me. These were good people, and I came to appreciate and love them dearly – they were ready to lay down their lives for a friend. After that incident, I tried to convince Emiel that I should leave, but he was insistent that I stay put.

Things were quiet for several days, and I was able to go out at night and size up the lay of the land. It wasn’t long, however, before the crops were up and the German’s established night patrols to stop the farmers from selling their produce locally. I was then confined to the attic or the courtyard and shed behind the house. Fuel was in very short supply, as was everything else, so Emiel would go out and appropriate sections of the fence from the local graveyard which I would cut up for the stove in the shed during the daytime. They also had tobacco leaves drying in the shed that I was able to help shred and roll into cigarettes to sell on the black market.

One day, I was working in the shed and there was a commotion at the front of the house. Alida, Emiel’s wife, came running to the shed calling “police.” I immediately ran to the field at the back of the shed because I couldn’t get back into the attic, but there was no place to hide in the field. At the end of the shed was a small room about six feet square where the nanny goat was kept – she was tethered diagonally across the room from the door. I slipped in and squeezed into the corner of the room on the same wall as the door. All the time, the excited talking was coming through the house and out into the courtyard. All of a sudden, the door of the room was yanked open and a black boot came through. The goat got excited and came ahead on her chain toward the door and the boot was withdrawn – I have had a great respect for goats ever since. The Gestapo soon left and I was able to get back into the attic. That night, I told Emiel that I was leaving, but he said that he had heard on the Radio BBC broadcast to the continent that the allies were about to invade France and would be in Belgium soon. This was his main argument for me to stay until finally, on September 9th, the Polish Division of the Canadian Army did arrive.

After the close call in the goat shed, I had to find a more accessible hiding place. Under the shed was a cesspool that Emiel bailed out once a week to fertilize the garden. This appeared to be the answer, but it was only needed once before I left the place. One day, there was a commotion at the house next door – the Gestapo broke in and dragged the man away. He did not return while I was there.

After the Allies had landed in France, each day brought hope of our district being liberated. The German troops had been rushing back and forth in convoys for weeks. One night, the horizon to the west was lit up by a continuous series of flashes – we thought at last the Allies were advancing. After several hours, we finally realized that what we had been watching was lightning, not artillery fire.

Up until this time, no one knew where I was. The Underground had not located me and Emiel didn’t know that they existed. One day, a young woman came to the house and, after much discussion, Emiel came and got me. She was the Underground contact and spoke good English. The next day, she came back and took me to a large house. Here I met several American airmen who had been shot down in the area and had been picked up by the Underground. Boy, what a way to hide – good food, a tennis court, the works. The owner of the house also owned a large hardwood processing plant next door where they manufactured shovel handles, wagon stocks, etc. I didn’t want to stay with the Underground, so I returned to my friends. On another occasion, they took Emiel and me to a banquet at a castle. Evidently, the owner of the castle owned the land around the village and probably most of the village as well.

The next morning, the whole village was a bustle. People were draping stringers, flags and bunting all over the buildings. Great news, the allies were just a few miles away and the village would be liberated by nightfall. Late in the after-noon, German tanks lined up south of the village and convoys of German troops poured into the streets – they were going to make a stand in the village. It looked like a shaky-do but, by morning, the Germans had retreated and the Poles were rushing through the village after them.

The next day, units of the 7th Armoured Cars from Winnipeg were parked outside the village. This was our first chance to talk to any of the allied military force. It appeared that the armoured cars had liberated a monastery just to the north and had liberated the winery as well. Anyway, there was only one guy that was in shape to talk. We got some soap off him and went back home. The next day, the Underground came and got Emiel and me once again and took us to the Burghermaster’s office. He took us onto a balcony eventually and, before us, the whole village square was packed with people. It reminded me of pictures of the Pope and the crowds at the Vatican. The mayor introduced each of us to the crowd and, although the Americans got a good hand, when I was introduced as a Canadian flyer, the response was thunderous. After this introduction, I was taken to the local jail. I didn’t know whether I was going into the pokey or what; however, they had captured a couple of German soldiers the night before and wanted me to see their prize. The Germans were just young kids, maybe 16 or 17 years old (Hitler Youth) and looked pretty dirty and hungry to me. I couldn’t speak German and they knew no English so it wasn’t much of a contact.

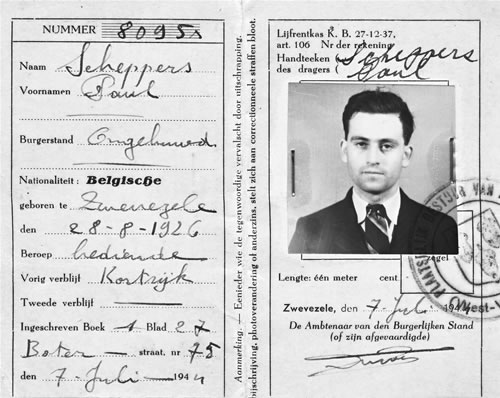

The mayor had a passport made out for me in case the Germans might overrun the area again before I could leave. My name was to be Paul Scheppers, this being the name of a local citizen they knew was dead.

Two days later, I was given transportation to join the Canadian Army at Brugge where a battle was in progress at a river crossing. A Colonel tried to recruit me into the Army but, knowing the likely fate of an untrained Lieutenant leading a squad, I respectfully declined. I stayed with them a day, and then got transportation back to a temporary runway behind the lines at St. Omar. On September 12, I was flown in an Anson to a base in the south of England. The next month was taken up with debriefings at RCAF headquarters in London, medicals, and trying to locate my gear which had been put into storage. I met up with Al Casey, who had also evaded capture; the other four members of our crew who had been taken prisoner would not return for another year. I got a pile of mail and learned that Kenny was doing fine. He had his operation and, other than some nerve damage, was doing well.

On our last flight, 13 Lancasters from 408 Squadron were joined by 59 Halifaxes from 420, 425, 426, 431, and 432 squadrons in our attack of the rail yards at Haine St. Pierre. According to the reports, the bombing was concentrated and the rail yards and locomotive shops were severely damaged. Six Halifaxes, including ours, and three Lancasters were shot down on this mission.

During its time in Europe, the 431 Squadron had taken heavy losses, especially in 1943 and 1944. We had lost 72 Halifaxes, and 313 men had died in action, 54 were missing, 104 were taken prisoner, and 18 had evaded capture after being shot down and had safely returned home. I was one of them.

On October 16, 1944, I was sent on survivor’s leave for 30 days, and that ended my part in the war. We had delivered 42,500 lbs of high explosive bombs, 19,000 lbs of incendiary bombs and 30 containers of leaflets to the enemy. Not too big a contribution after the hours of training.

We embarked at Southampton on the trooper Isle de France – this ship had been France’s pride and joy before the war as a luxury liner. On board, there were about 500 of us aircrew survivors on leave, several hundred English war brides with babies, and several hundred German prisoners of war. It was a relatively good crossing, taking six days to reach Halifax, where we boarded a troop train to Rockcliffe, near Ottawa.

In Rockcliffe, I came out of the shower and ran into an old friend, Len Rielly. Len had gone through all of his training with me and was pretty excited to see me as he knew that I had been missing and he thought that I was dead. Quite a few of the original flight had either been killed in action or listed as missing. Len’s reaction was sure spontaneous, and it was great to see.

At last, all the red tape was cut and we were off to home. I had never seen Kenny and was sure looking forward to meeting the little guy. He had gotten over his operation well, although it had left him with no control of his bladder, something that became more apparent as he got older. He was a beautiful baby. Helen and Kenny met me at Sicamous and, for the next month, we had a great leave, spending it between Armstrong and Ashcroft, visiting and trying to make plans for our future. While I was in Bomber Command in England, I was impressed with the teletype network that was the main communications between Group Headquarters and each of the squadrons. All of the orders were transmitted to the squadrons simultaneously by this means. I thought, surely this would be the field to get into after the war as companies would need to communicate the same way – head offices to branch offices, etc.

My leave was over far too soon when I received orders to report back to Rockcliffe en route to the United Kingdom. Most of the survivors were on base when I arrived, and the consensus of opinion was that it was a waste of time for us to go back to England and have to recrew and retrain because it looked like the war would be over before we could get back into action. The Pacific Theatre at that time was going hot and heavy, so we petitioned the Commanding Officer to route us to the Far East. The reply came back that we either go to England on the next draft or take our discharge from the service. Most of us decided to take our discharge. I was subsequently posted to Jericho Beach in Vancouver to be processed out.

- Date modified: