Order of events

1991

Violence erupts as communist government of Yugoslavia collapses

September 1991

Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) peacekeepers join European Community Monitoring Mission in the Balkans

Early 1992

United Nations Protection Force begin operations in the Balkans

15-16 September 1993

CAF members see heavy action in the Medak Pocket of Croatia

December 1995

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) launches its Implementation Force in Bosnia-Herzegovina

December 1996

NATO launches its Stabilization Force peace support efforts in Bosnia-Herzegovina

1999

Canadian pilots fly combat missions over Kosovo. Kosovo Force begins its mission there

2004

Last large CAF contingent leaves the Balkans but Canadian peacekeepers remain

Classroom materials

Canadians served in European Community, United Nations and North Atlantic Treaty Organization missions in Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia. These new countries arose from the ashes of the former country of Yugoslavia. As of 1991, tens of thousands of Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members joined these missions in the Balkans region of southeast Europe. They worked to restore peace and security to the people there.

A war-torn land

(June 1991 – July 1992)

After the breakup of Yugoslavia, the international community began peace support missions in the war-torn Balkans. Canada played a major role.

Yugoslavia

The nation of Yugoslavia emerged after the First World War which collapsed the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Some of the Slavic states in the Balkan Peninsula merged to form the new country of Yugoslavia. Its diverse population had various ethnic and religious groups with a long history of tense relationships. Yugoslavia faced hardships during the Second World War and battled occupation for years. After the Axis forces were finally forced out, Yugoslavia was reborn as a communist state.

Weakening of communism

In the 1980s, Yugoslavia's communist rule began to weaken. President-for-Life Josip Broz (better known as Tito) died in 1980. This was a serious blow to the country's unity. As economic conditions worsened, the strength of communism around the world weakened. Meanwhile, old rivalries between the different peoples of Yugoslavia were growing.

An elderly Serbian refugee couple search for a few personal effects in their destroyed home. Photo: Department of National Defence

Breakup of Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia's central government lost its ability to keep the country together. The states that made up Yugoslavia pushed to become their own countries. Tensions between ethnic and religious groups began to escalate. Slovenia and Croatia declared their independence in June 1991. Civil war soon spread across the Balkans.

The world responds

The outbreak of fighting brought an international reaction. Slovenia and military forces in the rest of Yugoslavia fought a brief war in the summer of 1991. To help enforce a ceasefire, the European Community Monitoring Mission was set up. CAF officers joined this multinational peace support effort in September 1991.

The United Nations Protection Force

Fighting erupted in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. In early 1992, the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) formed. It protected the civilians within three special “UN Protected Areas” in Croatia and kept other military forces out. By the time the original mandate of UNPROFOR came to an end in 1995, its mission had extended into the wider region. Peacekeepers from dozens of countries, including Canada, served in this effort.

Standing atop the Camp Normandy main entrance in Tomislavgrad, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Private Anthony Gruppuso of the Toronto Scottish Regiment takes the sunset watch. Photo: Department of National Defence

Canada's role

Canada played an important role in UNPROFOR efforts. Canadian soldiers went to the Balkans as a peacekeeping force. But they soon found out that there was often very little “peace” to “keep”. Many CAF members came under fire. This included intense action at the Medak Pocket in Croatia. Canadian troops saw their heaviest fighting since the Korean War during their time there.

Intense duties in Sarajevo

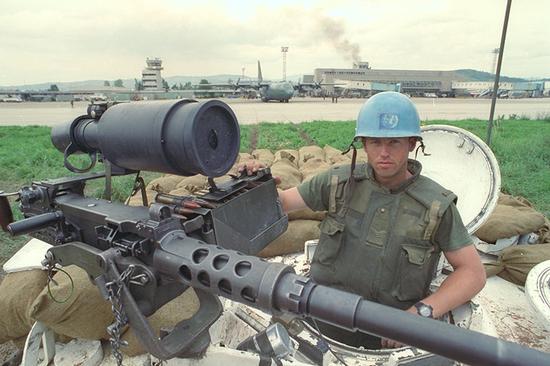

In the spring of 1992, fighting escalated in Bosnia-Herzegovina. UNPROFOR moved troops into that area. Their goal was to help the civilians trapped by the fighting and deliver humanitarian aid. A major part of the operation was to open the airport in Sarajevo so supplies could be flown in. In July 1992, as Canadian peacekeepers protected the airport and escorted relief convoys, they often came under fire.

Canada's Major-General Lewis MacKenzie commanded the United Nations (UN) forces in the Sarajevo Sector. He often made international news as he did his best to let the world know the harsh reality there. In the end, our peacekeeping efforts helped keep the vital flow of outside help coming in.

Sarajevo. A Canadian Armored Personnel Carrier drives through the well known "Sniper Alley." Photo: Department of National Defence

Further UNPROFOR contributions

Thousands of Canadian Armed Forces members would take part in UNPROFOR efforts. Almost every Canadian infantry battalion and armoured regiment spent time in the Balkans. CAF members played many other important roles during their time with the UNPROFOR. Our service members supplied military engineering, mine clearance, logistical support, electronic warfare and air control capabilities. Canadian warships patrolled the Adriatic Sea to help the UN block arms shipments to the region. Canadian aircraft enforced the UN's no-fly zones and prevented the warring sides from buying weapons.

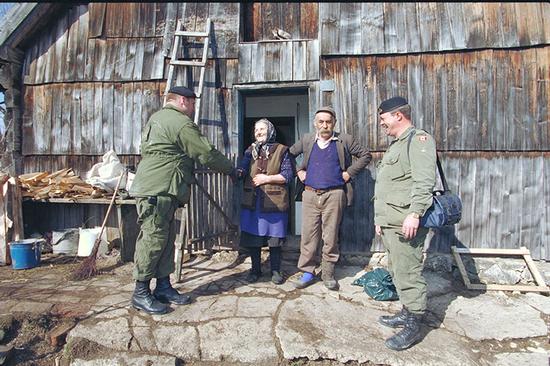

Through it all, Canadian peacekeepers helped the local people a lot in a variety of ways. For example, they protected humanitarian aid convoys and hospital patients. They also volunteered time and money to donate school supplies and fix damaged buildings.

The Medak Pocket

(15 – 16 September 1993)

Tasked with protecting civilians in Croatia, Canadian Armed Forces came under heavy fire.

Croatian offensive

In September 1993, Croatian and Serbian forces fought in the Lika region of southern Croatia. On September 9, Croatian troops attacked near the town of Medak and pushed the Serbian line back. This created the so-called “Medak Pocket,” Croatian-held territory populated by Serbian people.

Negotiating a ceasefire

Political and public pressure forced the Croatian forces to agree to a ceasefire with the Serbs. The terms of the agreement required both forces to return to their original positions and leave the Medak Pocket on September 15. It fell to UN peace support troops to enforce the fragile agreement.

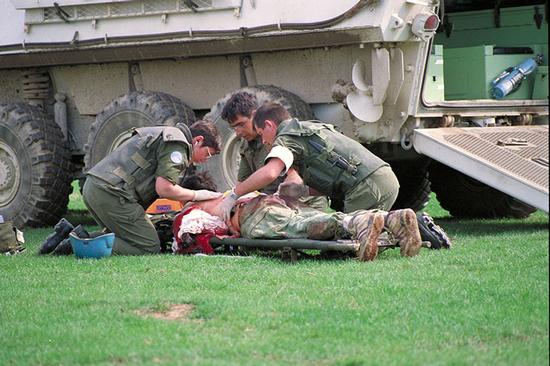

UN Duty in Bosnia. Photo: Department of National Defence

Canadian soldiers in the middle

The 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry were the best UN troops available for this mission. Supported by two companies of French soldiers, they were to enter the Medak Pocket and make sure both sides left. They were also to help refugees return to their homes in the area.

On September 15, as the Canadian and French troops advanced, Croatian forces began firing on them. The UN troops dug in and created a defensive line. Croatian artillery, rifle and machine gun fire poured in. The Canadians returned fire to defend themselves from the attack. They drove the Croatian forces back over the next 15 hours. It was the heaviest action that Canadian troops had experienced since the Korean War.

A standoff with the world watching

The Canadian commander Lieutenant-Colonel James Calvin negotiated with the Croatian forces. They agreed to withdraw at noon on September 16. But when the UN troops tried to enter the Medak Pocket, they still faced a Croatian roadblock and minefield.

Evidence suggested our troops were being kept out so the Croatians could complete ethnic cleansing there. So Lieutenant-Colonel Calvin held a news conference with international reporters at the scene. He said the Croatian forces were not holding up their end of the ceasefire agreement and hiding their attacks on Serbian civilians. The Croatian forces finally backed down and allowed the UN troops to pass.

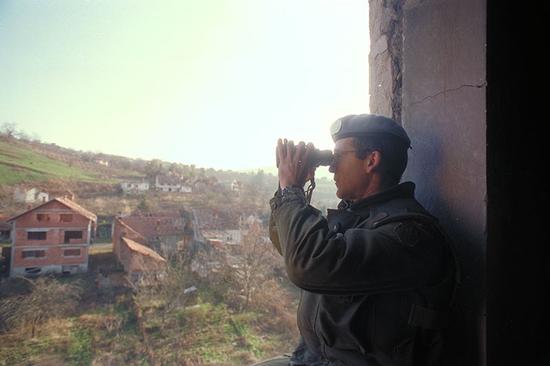

Members of PPCLI keep watch for any dangerous movement in the area. Photo: Department of National Defence

The aftermath in the Medak Pocket

The UN forces could finally enter the Medak Pocket. They discovered evidence of horrible violence against the local people. Many Serbian villagers were dead—victims of what looked to be ethnic cleansing by Croatian troops. The Canadians recorded in detail what they found in the villages. Their records were part of later war crimes investigations. Four Canadian soldiers were wounded during the fighting at the Medak Pocket. But the UN forces had persevered. They forced the Croatians to cut short their ethnic cleansing and prevented more civilian deaths.

A special commendation

In 2002, Governor General Adrienne Clarkson recognized Canadians who fought in the Medak Pocket. She awarded the Commander-in-Chief Unit Commendation to the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. This award goes to any unit or sub-unit “that has performed an extraordinary deed or activity of a rare high standard in extremely hazardous circumstances.”

NATO efforts in the Balkans

March 1999 – April 2004

Canadian Armed Forces warplanes took part in NATO air strikes in Kosovo. They saw some of their heaviest action since the Korean War.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization takes over

The original mandate for UNPROFOR ended in the spring of 1995. Three different multinational forces took over its roles in the Balkans. Two were in Macedonia and Croatia. A restructured UNPROFOR continued in Bosnia and Herzegovina. By December, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) had taken over most of the peace support duties in the region. CAF members continued to serve in the Balkans, but now it would be as part of a new NATO mission.

A CH-146 Griffon Helicopter from 408 Tactical Helicopter Squadron, CFB Edmonton, flies a mission carrying the Quick Reaction Force past the ruins of an old castle near Velika Kladusa, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photo: Department of National Defence

NATO Implementation Force

The Dayton Peace Accord of December 1995 laid out the terms to end the fighting in Bosnia and Herzegovina. A multinational peace Implementation Force patrolled the ceasefire lines and other borders. It helped keep citizens safe, assist local police forces and monitor elections. The Implementation Force also helped refugees return and rebuild the economy.

More than 1,000 CAF members served with the Implementation Force in many roles. This included a headquarters group, a reconnaissance squadron, a mechanized infantry company, an engineer squadron, and command and support elements.

NATO Stabilization Force

The Stabilization Force was the next phase of NATO peace support efforts in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Formed in December 1996, it saw multinational peace support troops patrol the country. It helped establish lasting peace in the war-torn land. Its goal was to help set up a democratic nation that would sustain the peace process without help from multinational peace support forces. Some 1,200 CAF members would serve with the Stabilization Force.

Canadian Armed Forces diver in Zgon, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photo: Department of National Defence

Unrest in Kosovo

In 1998, the Serbian military and the local Albanians began fighting in Kosovo. Despite attempts by NATO to enforce peace, the violence continued. The Serbian military repeatedly attacked civilian Albanian residents in Kosovo. NATO threatened military action against the Serbians if a lasting ceasefire was not signed. When negotiations failed, NATO forces began an air campaign.

Operation Allied Force

Operation Allied Force was the code name given to the NATO bombing campaign in Kosovo. Its goal was to drive the Serbian military out of Kosovo. In March 1999, Canada committed six CF-18 jets—a number that grew to 18 by the end of the mission. Canadian warplanes made up 10% of the missions flown in Kosovo. This was the first time Canadian pilots flew combat missions since the Korean War.

Operation Harmony, Sarajevo. Private Pierre Lévesque at the airport in Sarajevo. Photo: Department of National Defence

Ceasefire

The NATO bombing campaign did a lot of damage and took a toll on the Serbian forces in Kosovo. With its plans to end the bombing, NATO deployed ground forces to Kosovo and nearby Macedonia. In June, Serbian forces accepted a ceasefire agreement and NATO's Kosovo Force rolled in.

Canada's role in the Kosovo Force

Canada initially dedicated roughly 800 peace support troops to the Kosovo Force, and soon added 500. Canadians helped maintain the fragile peace, protected civilians and provided reconnaissance support. The CAF deployed an armoured reconnaissance squadron, a tactical helicopter squadron, a field engineer squadron, an infantry battle group, and command and logistical supports elements.

They led patrols and monitored activities. Our soldiers also carried out many humanitarian aid projects in Kosovo. They rebuilt damaged schools and medical facilities. They installed small bridges and put up playgrounds for local children.

In December 1999, the first Canadians to serve in the Kosovo Force rotated out. By June 2000, most of the Canadian military personnel had left.

Corporals Rob Serjeant (left) and Rob Majore (right) clear debris from the road near Kiseljak, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sergeant Pat Gear in the background supervises some work of the Drott excavator. Photo: Department of National Defence

On the road to peace

By December 2003, the situation in Bosnia had improved. NATO reduced the size of the Kosovo Force and the Canadian contingent dropped to about 650 people by April 2004. The European Union Force led the multinational peace support troops in late 2004. As the mission evolved into this new form, the number of CAF members in the country reduced to less than 85.

A Liaison and Observation Team led Canada's role with the European Union Force. These troops kept in close contact with local authorities, police departments, community leaders and army units. They helped develop a peaceful society, collect illegal weapons and prevent smuggling. As a lasting peace took root, the CAF withdrew its last troops from Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2007.

A handful of CAF members are still serving in the Balkans today. The region has recovered since the devastating civil wars that swept through the former country of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. Almost 40,000 Canadian peacekeepers served there over the years. They played a major role in helping achieve this hard-won security and stability.

Canadian Armed Forces military policemen preparing for patrols in Zgon, Bosnia-Herzegovina. (Photo: Master Corporal Bernie Tessier. Department of National Defence ZN2004-003-003)

Sacrifice

Canadians can be proud of our country's reputation around the world as a force for peace, but this comes at a price. About 130 Canadians have died in the course of international peace support operations. In the Balkans, 23 of our service members died and many more were injured.

The wounds of peacekeeping are not always caused by hostile fire, land mines or accidents. Sometimes the scars of service are psychological. Canada's military efforts in the Balkans were particularly difficult for our soldiers. The war crimes and atrocities committed against the civilian population there were horrific. Witnessing such human brutality often has a deep impact on those who see it.

- Date modified: