Memoirs of Gordie Bannerman

Going Home

Holland, December 1945. The great moment has finally arrived! WE ARE GOING HOME! We received the news that on or about December 20, 1945 we were to bid our Dutch friends farewell and leave the town of Winschoten. With many thoughts and emotions we cleaned up the school where our men were housed. Extra civilian things that we had acquired we either gave away or left for the Dutch. We left Winschoten about 5 a.m. on December 20, 1945. I, along with the rest of our troop, trudged along the street in the darkness to waiting lorries. Here we did a roll call making sure no one was left behind that had slept in or failed to show on such an important morning of our lives. The correct answer to the roll call as I made my report to Capt Forbes was, all present and correct sir. Let us get loaded and away. All of us were leaving Winschoten. The words parting was sweet sorrow. All the girls and friends were left behind.

In one sense the troop were rather sombre since we were leaving a place that had been home to us for eight months. The Dutch had been extremely kind to all of us and I must give them a tremendous amount of credit as they with took us to their hearts and homes as if we were their own family. Thank you, good folk, we loved you.

On the lorries, as we pulled away from Winschoten, the mood brightened a bit. As we travelled some caught some sleep, others wondered how much time would we spend in England before we finally were on board ship for home. Our first stop was the large staging camp at Nijmegen where all were assigned to huts and given orders when we would leave. Greeting us at Nijmegen were large signs warning us to turn in any small arms like Lugers, P38's, and any other firearms. If we did not turn these weapons in we would be sent to the army of occupation in Germany for a year. This was a very serious thing as most of us had Lugers and other non issue revolvers. Chuck Watson and I had a talk and said we were not going to throw away our revolvers and when the time came to board a ship or leave this camp we would stand together. So if one was caught with prohibited firearms the chance would be both would be caught and we then would go to Germany together.

We spent a day or so at Nijmegen and soon boarded a train to Ostend. All along this route the railway workers would have picked up hundreds of revolvers as the fellows really believed we would have a harsh inspection at Ostend and were throwing them out the windows. Chuck and I kept ours. We arrived at Ostend with no inspection, and finally on board the Dover Queen to cross the channel with a sigh of relief, and one of joy. We were on our way HOME. England then Canada and that cannot happen too soon.

On board the Dover Queen in December, 1945. We have left the continent and here we were on a channel ferry heading for England then we hope soon to be on our way home. Landing at Dover we were directed to get onboard the rail cars for our trip to Aldershot. The English countryside never looked better as we steamed through to our destination.

Arriving in Aldershot we marched from the station to almost the same barracks that we had marched to in 1941. Now we were almost five years older. Once settled in our barracks we had a medical and instructions on how to mark our kit bags. Any extra kit or trunks were painted with a mark that designated our destination. Here we were down to one officer in the battery, Capt Murray Forbes, who would be with us until we arrived back in Indian Head, Saskatchewan. After documentation we were off on Christmas leave.

I had said all my good-byes to all my Scottish relatives on my last leave so I decided to go to Nottingham with Staff Sgt. Ed Noseworthy. I had never been in Nottingham, the home of Robin Hood, Sherwood Forest. Ed and I went to an excellent hotel and acquired a room. Then out on the town for the evening. This city recently had thousands of American troops stationed here. But with the war against Japan still on the Americans were almost all gone except administrative staff. Ed and I stepped into the first likely looking pub. On entering we had the feeling we were being undressed. Nottingham was a large industrial centre and this centre was probably the largest textile manufacturing city in England. This industry employed thousands of women and in this pub must have been about one hundred women and no men.

I know what a girl or women must feel like to walk down a street where there is a couple of hundred soldiers all lined up all eyes on her. Ed took this all in stride and we bought a drink and even had a drink sent to our table from a couple of the ladies. Almost all the ladies had, while the Americans were here, bleached their hair so were blonds with their own color coming in. The ladies were all ages, young and old. Ed took a liking to one of the ladies who joined us at our table. She brought a friend. She said her folks would only be too glad to feed me Christmas dinner. [She stood me up.]

Looking back on the whole evening this girl lived out through Robin Hood Close and I think the offer that her folks would be glad to feed me Christmas dinner was a way of walking her home through the dark wood. Oh well, I had Christmas dinner at an American kitchen that fed any serviceman that came in. Turkey and all the trimmings and I had a massive drumstick. Ed and his lady friend could not enter as the girl friend was a civilian so Ed ate elsewhere. English girls were standing outside hoping to get a Christmas dinner, but the American troops would not let them in. Quite a few of these ladies were pregnant and their American boy friends long departed. This happened all over where ever troops had been stationed. Our leave over and back to Aldershot.

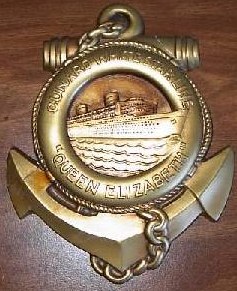

New Year came and went and we had not been notified when we were to leave England. We were finally notified no more leaves and to be packed and ready to catch the train. On January 9th, none of us missed that parade to the train, destination Southampton to board the liner the Queen Elizabeth. We still could not believe we were on our way.

I still have my boarding pass, and the ship is TA260, and our unit has been numbered E-57. L35064 Rank BSM. Bannerman G. We boarded the ship. We had been taken under control of people with Movement Control. All extremely well organized.

Captain Forbes, our officer commanding, went with other officers while myself and other sergeants were given instructions to go where directed. I was directed to a state room which was not very big, but it had six bunks and each of us were allotted a bunk bed. The other five in the room were WO2s from different units. I do not think any of the five were combatants. After getting settled in I went to find out where our battery personnel were located. They were in large rooms with bunks bed in rows ten high, so there was probably two hundred to the large room. We were all pinching ourselves. Were we really going home?

On board the Queen Elizabeth were 12,800 troops, male and female, most from the 5th Armoured Division. The female group from the CWAC. Some air force personnel and Sir Winston Churchill along with Mrs. Churchill, and their daughter Mary. We did not see the Churchill family and I believe the rank of Colonel and up were able to hob knob with them.

All went without a hitch down to the time you went for meals, the table and seating partners all laid out. Two meals a day and they were good meals, not the old Oronsay fare when we went over to England in 1941. The Queen Elizabeth made so many trips taking American troops home. The ship would have been provisioned in New York so there was good food, even ice-cream. I do not remember what time we felt the giant ship start to move out of Southampton, but we now knew no blackout, no submarine worry, and every turn of the massive propellers moved us closer to CANADA ...........and........ HOME.

I would say all service personnel would think about food so the two meals a day on board ship meant that you did not forget the time you were to attend your meal sitting, or your table that you shared with another eleven people. Six of my meal companions were air force flight sergeants who were home bound from being stationed in South Africa, and the other six, which included myself, had spent about five years overseas. They had been about two years in the air force, trained in Canada and just before the war ended had been sent to South Africa. With probable service in the far east the Japanese surrendered so they were no longer needed. They, like us, were on their way home. Now this group had never seen a shot fired or did any operational flying [lucky for them].

What we old timers found out at our meal time was there was exactly twelve portions on each platter so you had your portion no more, then passed the platter to the next person. The air force had manners like nothing I had seen. They had to be told to pass on the platters or one of them would pull a gravy laden chop over the side of the platter making a real mess. In five days, ten meals with these fellows they soon found out that we all shared, no hogs, and a little manners went a long way in this man's world.

Most of the trip the weather was pretty good with the wake of this large ship disappearing into the receding horizon. At night, if you wished to be alone with your thoughts, you could stand at the stern of the boat watching the fluorescent sparkles in the water. One day we had a bit of rough weather and one of the CWACs fell down the massive stairs that led to the ballroom breaking an arm. Winston Churchill came on the public address system and in his finest, stentorian voice he welcomed all that were sailing with him and his family. Then he went on to the Stout Ship, Stout Commodore then the Stout crew. His voice trailed away never to complete his Stout message.

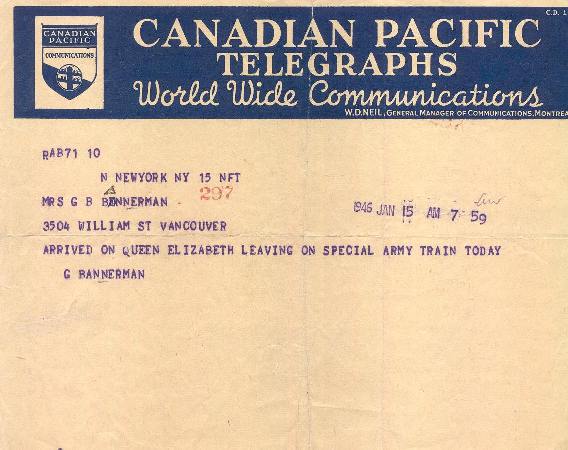

About the third or fourth day we were given some information on our disembarking procedure plus telegram forms that could be sent to our folks and anyone else informing them that we had landed. These cables were sent when we landed in the States. On the fifth day we sailed down the Hudson River towards New York. I did not see the statue of Liberty as it was my meal time and I was not to miss a meal. Soon we were tied up at the berth in New York. We knew we were nearly there and now the suspense of waiting to disembark. I remember our turn came in a late afternoon.

I have a copy of the Regina Leader Post January 19, 1946 and it details all the Saskatchewan Artillery units coming home to the small towns along the main line CPR. In this edition is a picture of we seven originals of the 76th Battery. This was the last crossing that the Queen Elizabeth carried troops.

Our battery had all been reunited and with full packs we waited for our turn to march off the Queen Elizabeth. It seemed quite a wait, but that did not bother us as in a few moments we were down a gang way and standing dockside. A number of American Red Cross ladies were handing out doughnuts and cardboard containers of milk, also coffee and maybe soft drinks. The first drink of milk any of us had in years. There was a band playing as the ship docked. All down the Hudson River banners stories high had WELCOME HOME BOYS. Not much time was spent on the dock and we were instructed to board a ferry to take us to Newark, New Jersey. We marched onto waiting trains to take us home. As we journeyed through the countryside we kept looking out and enjoying each minute of the trip

The area we were travelling through was well snow covered. We were going along all pretty quiet lost in our own thoughts when one of our fellows hollered, “Gordie come quickly.” I ran down the rail car to where this fellow stood and he was looking out the window of the train and said, “Look Gordie rabbit tracks!” A Canadian boy knew we were close to home when you saw rabbit tracks. The train rolled along, the wheels putting out the same noise as they did when we went overseas. Remember the next time you are on a train and the wheels go jacks and sixes, jacks and sixes. Think of the tens of thousands of servicemen and women who went to embarkation points with that jacks and sixes refrain in their memory.

While on the train we were able to send telegrams to folks along the way in hope they would meet our train. As we pulled into Kenora, Ontario quite a few of the old regiment were down at the station, but they were now civilians and there was that sense of distance. They had formed a great part in our lives, but now it was so strange to talk to these civilians and I even think they found that we were different too. That part of our stop I find it hard to explain.

I had sent a wire to Norma Ainlay who was working in Winnipeg to let her know would be coming through. Norma had wrote many letters to me overseas. Norma, in the year of 1938, was holidaying at Lac Pelletier with her mum and sisters, all from the small town of Pambrun. I was at a dance at the lake and after the dance was to walk Norma to her cabin. I was wearing my first felt hat large brimmed and when Norma and I went to kiss good night, the brim hit her on the forehead and rolled off down toward the lake with me in pursuit. I caught the hat in a flash, but Norma was gone into their cabin.

At about midnight I was already to step out on the platform as soon as the train stopped. Norma was there waiting along with an older woman who said, “Where is Orme?” This lady was Orme's aunt and she had found out from Norma that Orme and I were due in this night. Orme's aunt was able to get Norma up to the train side as she had worked during the war serving coffee to the troop trains. I went back on the train to shake Orme awake as his aunt was outside waiting. Orme and his aunt and Norma and I were all standing on the platform. Norma kept jumping up and down and would hug and kiss me then do the same for Orme. All the time exclaiming aren't you fellows excited to being almost home? I guess we were, but still could not believe we were so close to home.

As the train clicked the miles across the prairie we went through home towns of many of our fellows. Somewhere east of Indian Head on the CPR we were interviewed by a reporter from the Regina Leader Post who did a write up and a picture of the seven original battery members coming back to the 76th Bty Armoury at Indian Head where we would finally sever our connection with the battery. The seven members were RSM George Green, BSM Gordie Bannerman, Sergeants Orme Payne, Jack Parr, Bert Townsend, Chuck Watson, and Peter Powless.

Arriving at Indian Head we stepped off the train to a band playing and a great welcoming committee. I assembled the battery and turned the parade over to Capt Murray Forbes and we then marched off to the armoury for a dinner and a drink. BSM Bill Lloyd and I marched to the armoury for the speeches, drinks and food.

Murray Forbe's dad was a judge and had a car so he drove Orme, me and his son Murray into Regina, Saskatchewan. Either the 19th or 20th of January, 1946, Orme and I arrived in Regina in the late afternoon. We requested to be dropped off near a Saskatchewan Liquor store. Thanking Judge Forbes, saluting Capt. Forbes, and wishing him farewell, Orme and I complete with packs were on the snowy icy streets in Regina. The next step was almost fatal as I went to enter the liquor store and my steel shod boot slipped on the icy sidewalk and my head, hind end, and heels all struck the pavement with a terrific whack! Stars floated for a moment, but up I stood and seemed not too bad off. Then I slipped and fell again. Not a good start for someone who survived the war to almost crack his skull first day of his home coming.

L/Sgt.. Elmer Applegren had missed the battery draft in England, but came home the same time as us. Elmer was on the same mission that we were, to buy a Saskatchewan Mickey. He had joined with us and served the whole time. After two falls I entered the liquor store and we made our purchases. The next step was to phone Edith, and R.J. Wood who said, “Get a taxi and come and stay with us.” which we did. R. J. Wood was Orme's and my school teacher before the war and he was instrumental in us joining the 60th Bty as a militia unit. R.J. Wood was our attestation officer when we joined active service. He was a 2/ Lt. in July 1940, but rose to the rank of major and was second in command of the artillery holding unit Camp Borden, England.

He became a 2/Lt. in July, 1940 on active service with 60th Bty RCA, he rose in rank to Captain and was a troop commander. Capt. Wood was an excellent officer both in appearance and his knowledge of gunnery. He was a superb fall of shot observer and it looked like he had a great career ahead of him. Tragedy struck on the May 22, 1942. While riding a motorcycle, checking regimental road discipline, his motor cycle crashed into a bus or lorry. Near death, this man was pretty tough and survived the crash losing an eye and some terrific facial injury. He would have been slated to be sent home, but he had signed up for the long haul and an accident like this was not to send him home. He was, in time, promoted to major and served under Colonel Townsley at the artillery holding unit Camp Borden, England until war's end.

We had a warm welcome from Edith Wood as we arrived on her door step. Edith Wood always thought of Orme and I as the kids. Edith Wood knew Orme and I from the time we were little boys and more than likely her aunt was the midwife when we were born. Regina Saskatchewan looked cold, but the prairie welcome from the Wood family was the greatest. The heat and dryness of the prairie houses was hard to take especially after living out doors and unheated buildings as long as we had. We did not get much sleep the first night and were up early next morning, I must say a bit hung over. RJ said we needed a shot of ENO effervescent salts to clear the cobwebs. He then presented me with a bubbling glass with the recommendation to just swallow it down for the best effect. I did, but immediately rushed to the bathroom. The prankster RJ had mixed the ENO's with about three ounces of Gin and that is getting more than the one that bit you.

During our stay in Regina many old friends that were in the city came to visit and welcome us back. I was on the phone telling the ones that were girls how nice it was to hear Canadian girls voices once again. We were full of the joy of being alive.

Soon Orme and I caught the train to Swift Current, Saskatchewan where Orme's Dad was to take us to their home at Neville (also my old home town, my folks now at the coast). We pulled into the CPR station at Swift Current and I was first off the train. Here was Orme's dad waiting, also Frank Murphy. Cliff said, “Where is Orme?” I said, “He is putting on his jacket.” Finally Orme came out to be greeted by his Dad. Frank Murphy and Cliff Payne said seeing it is so late and the roads pretty icy and snow covered, we would stay in Swift Current that night. Cliff had booked a room in the nearby hotel. Gathering up our gear we went to the hotel room. The stories started and it went on and on.

We had just nicely turned in for the night when Gerry Payne, Jim Bedard and a whole group of Neville hockey players entered our room to welcome us back. These young men were mere kids when we had left for overseas and here they were grown men. The next day we went to Orme's Mum and Dad's place in Neville. We received a great welcome from young and old. You would think we were heroes when all we did was go through the whole war and get home safe. I stayed in Neville for a few days as the ladies of the district were to present Orme Payne, Floyd Donnelly and I with our regimental crests and a scroll thanking us for our war effort. It was a great evening and old friends never looked better.

I went back to Regina to get a trunk from MD 12 and shipped it to Vancouver, also picked up travel warrants to Vancouver. Returning from Regina to Swift Current I located Paul and Mary Wells from Neville who were in the city to pick up a couple of relations. Paul said I could ride with them to Neville. The trip from Swift Current to Neville on a snowy, wind blown stormy night was something else, almost our end. As we journeyed down the highway we ran into many drifts of snow that almost blocked the road. With five people in the car, Paul was able to crash through all the drifts, but about four miles west of Neville we hit a drift that finished our movement. STUCK!!

Try as we might with shovelling and pushing, we could not get out of the snow drift. It looked like we would be here for the rest of the night. Paul, Mary Wells and I were warm enough. Their Aunt was from Florida and the nephew was a Marine just returned from the Pacific. Neither of them were clothed for warmth, so the decision was to run the car motor at intervals to provide us with heat. We would take turns in digging out the exhaust pipe so we would not get carbon monoxide poisoning. I was not too worried and in my army great coat, battle dress, wool shirt and wool underwear was quite warm and would have curled up and went to sleep. Paul kept telling Mary not to let Gordie me sleep. Even with only running the car motor at intervals the gas tank went dry. This was a about 5 a.m. Outside temperature about -30 Fahrenheit and a strong west wind piling the snow deeper around us.

We just cuddled a little closer and waited for day light. When it was light Paul and his nephew walked to the nearest farm folk which was the Hamm family. Mr Hamm came to the rescue with a team of horses and a sled. Mary, the Aunt, and I clambered through the drifts to the sled and back to the Hamm farm house. Here hot coffee, a bowl of soup and we were ready to face the day. Thankful that we did not freeze in the drift. I thought I had one up on Orme so when we were taken back into Neville I saw Orme and told him we nearly had a tragic ending in a snow drift last night. His answer, “So did I!” Glenn Davis and Orme were coming from a dance at Pambrun on the east side of Neville and they were stuck in a drift as we were.

At last we drove in to the Payne's yard and into their new house (new location, they had lost the other home to a fire) to be welcomed by Orme's Mum, Beatrice, and of course the rest of the family, Gerry, Patsy, and Judy 6. Orme was now indeed home and the welcome was warm to us both. Another couple was Orme's uncle and aunt, Bud and Mamie Murphy and their family. I owe Mamie Murphy a great thank you as she was a neighbour to my folks when Dad, George and I were in the service. Mamie's stories, laughter and support was a tremendous boost for my Mum. Others in this small town that help shape my formative years were many and I could not begin to name or thank them all. Harry and Mary McNairn a great pair with Eunice and Buck as family. It was Harry that changed my name from being called Gordon to Gordie.

On the train to Swift Current I had the company of Bob Murphy a great story teller and a homesteader like my Dad. When overseas Orme and I used to tell the Bob Murphy stories and when we ran out of them we made them up. I stayed in Swift Current that night and the CPR transcontinental train would have been west bound about midnight and I was on it without any of the other battery members. I was on my way to my folks. I checked in with the sleeping car porter and it was into my bunk and soon asleep on my last leg of the journey that started almost six years ago. The circle was almost complete.

I remember when I awoke the first morning on the train we were pulling into Calgary. I had a great meal in the diner and on through Banff. I saw my first wolf running along on the lake ice, herds of elk both around the Banff station and all along the railroad for miles. It was not hard to strike up friends on the train. Quite a few service men and women going home like I was, plus others going to the coast to work. Through the mountains down along the Fraser river and into Vancouver passing along the trade mark building of Rogers Sugar refinery and slowly entered the Vancouver CPR rail Station. Excited probably, apprehensive maybe, just glad I survived and ready to get off the train and meet Mum and Dad. What a wonderful feeling came over me at this point.

At the end of January 1946 I was finally back within a flight of steps from meeting my folks once again. The last time I had seen them was September 1941 when I had been home on embarkation leave. I gathered up my pack, said good bye to fellow passengers that I had met along the way, went over to the stairway and walked up the stairs. There waiting was Mum and Dad. We were overjoyed to see each other and get and receive a hug or two. The feeling was, am I really here? I may have appeared a bit distant. Why? I do not know. It had been a long while with just hundreds of letters from home through all the intervening years. Had I left the boy behind or what?

Mum said I must be hungry. That was always like Mum, she fed everyone that ever crossed the threshold of their home. We crossed the street to Spencer's Department Store and had a snack then on to the street car and home to their new home at 3504 William St., East Vancouver. Mum of course wondered how I was? How was Orme? When I last was with him and questions about my coming back and spending some time in our old home town of Neville, Saskatchewan. My sister Marjorie was at the Vancouver General Hospital where she was a nurse in training and would not get off to come home I think until another day and my brother Don was at school, so was my youngest brother Arnold. Mum had just said to me that Arnold would soon be home from school. Arnold was almost six when I went overseas and now was now almost 11. Well as I looked out the window to see if Arnold was about to arrive and sure enough he came running down the street and into the yard and roared up the stairs hollering Gordie, you're home! That was a great welcome from Arnold.

When Don came in from Tech school he was not as exuberant as Arnold, but was mighty pleased to see me home. Don had grown from just a boy of 11 to a young man of 16 and a half. When Marjorie came home from the hospital it was a day or so later. Marjorie was glad to see me home and had grown into a fine looking young lady working at her nursing career. She had really been a stalwart to Mum when Dad, George and I were away in the forces for which we owe her a lot. Now the only one of the family I was yet to see was George as he was still in uniform at NDHQ Ottawa as a staff Captain. He hoped to be discharged soon, then enroll in the engineering faculty at the University of Saskatchewan. I was finally home. Quite a long route with some days when you thought maybe you would not survive, but my family must had some pull with higher powers because I made it home.

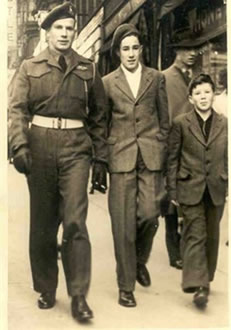

Mum Bannerman was a very unselfish wonderful person and this photo was a wish of Mum's. At long last all of her family were home and under Dad and Mum's roof once again. George and I from overseas, and now out of uniform, and Dad home out of uniform too. Mum very seldom ever said how she would wish for something, but rather took the actual happenings and dealt with it at the time. Going out for this photo was a very special day for all of us and the first time in five years that we were altogether. Mum and Dad took us all to Scott's cafe on Granville St. in Vancouver for a special family meal. With Mum seated with us, not up and down from her meal looking out for the rest of the family. I do not know if we had the photo taken before we ate or not, but whatever it was on to Jerome's studio for the photo.

During the war I thought that my early up bringing helped me retain my nerve. As a child I never came home without one or both parents at home. I never went to bed without one or both parents in the house. When a terrible blizzard blew for days on the prairie one or both parents stayed up to watch the fire so that we would not freeze, or the house burn down around us. When I bedded down in my slit trench and I pulled this invisible security blanket over me knowing that while asleep nothing would happen to me and it did not. When I awoke the next morning my nerves were rested and I was able to face another day.

The Battle of Otterloo happened on the night of April 16/17, 1945. On this night Fox Troop had quite an engagement with the enemy. This resulted in the deaths of two of our fellow gunners and the wounding of around twelve or so more. One of the gunners, Ken Nicolson, was badly wounded in the command post house and died before he could be evacuated. For fifty years I carried a load of guilt about Ken's death. I blamed myself for not getting him out of the house to an aid post. For all those years after I thought about this and every time I looked in the mirror I thought about it. I never told any one. Not Edith, our son Gordie, or Orme Payne, my best friend, until I think about fifty years after Otterloo. We were at a birthday gathering of Lloyd Fraser's at the Old Dutch Inn. I was seated across from Don Bulloch who at the time of Otterloo was with me in the command post. We must have mentioned Ken Nicolson and his death and it triggered the fact I had to tell someone how I felt all these years.

Don was very supportive and assured me in no uncertain terms that I was not to blame for Ken Nicolson's death and that Ken had not lived for long after being hit with Schmeiser fire in the abdomen. I felt some better and then in a day or so after this conversation with Don Bulloch I had a call from Don and he said he and Fred Lockhart were coming to talk to me the following day about Ken's death. This is when I told Edith and Gordie about the long time guilt that I felt. I must say they were very understanding. The following day Don and Fred arrived and we talked over all the events of that night. Don and Fred were with me at the command post and both had been in the room of the house when Ken was hit with the submachine gun fire.

Both men had made the trip to see me entirely on their own. We talked for over two hours on everything that happened that night so long ago. The load they lifted off my shoulders only I can tell you. The visit by these two comrades was something I will remember all my life. They were both in agreement that all had been done to help Ken Nicolson from the time he was hit, being bandaged by Vic Bennet, and his death soon after. When I said a load lifted, it certainly was.

Thanks to all after all these years, especially Edith for being there for me and our son Gordie, Don Bulloch and Fred Lockhart, and Orme Payne who looked out for each other for many years. Too many others to name I owe for their support during the war and after, THANKS.

- Date modified: