When I got to Stalag Luft 3 I was assigned a barrack called

Number 104, and it was a building which was quite long and had

perhaps as many as 120 to 150 men in it. It was broken up into

relatively small rooms, not much bigger than this one, and there

were two-tiered bunks in it. It turned out that it was almost all

New Zealanders, the whole of that hut. The senior officer,

in fact, was a Wing Commander Blake who had been shot down

several years before. He was in Fighter Command. The room

that I was actually assigned to, there were 12 of us in the room,

and they said, "You know, we're having a little trouble with our

senior officer here. He's getting very uppity. We have to play

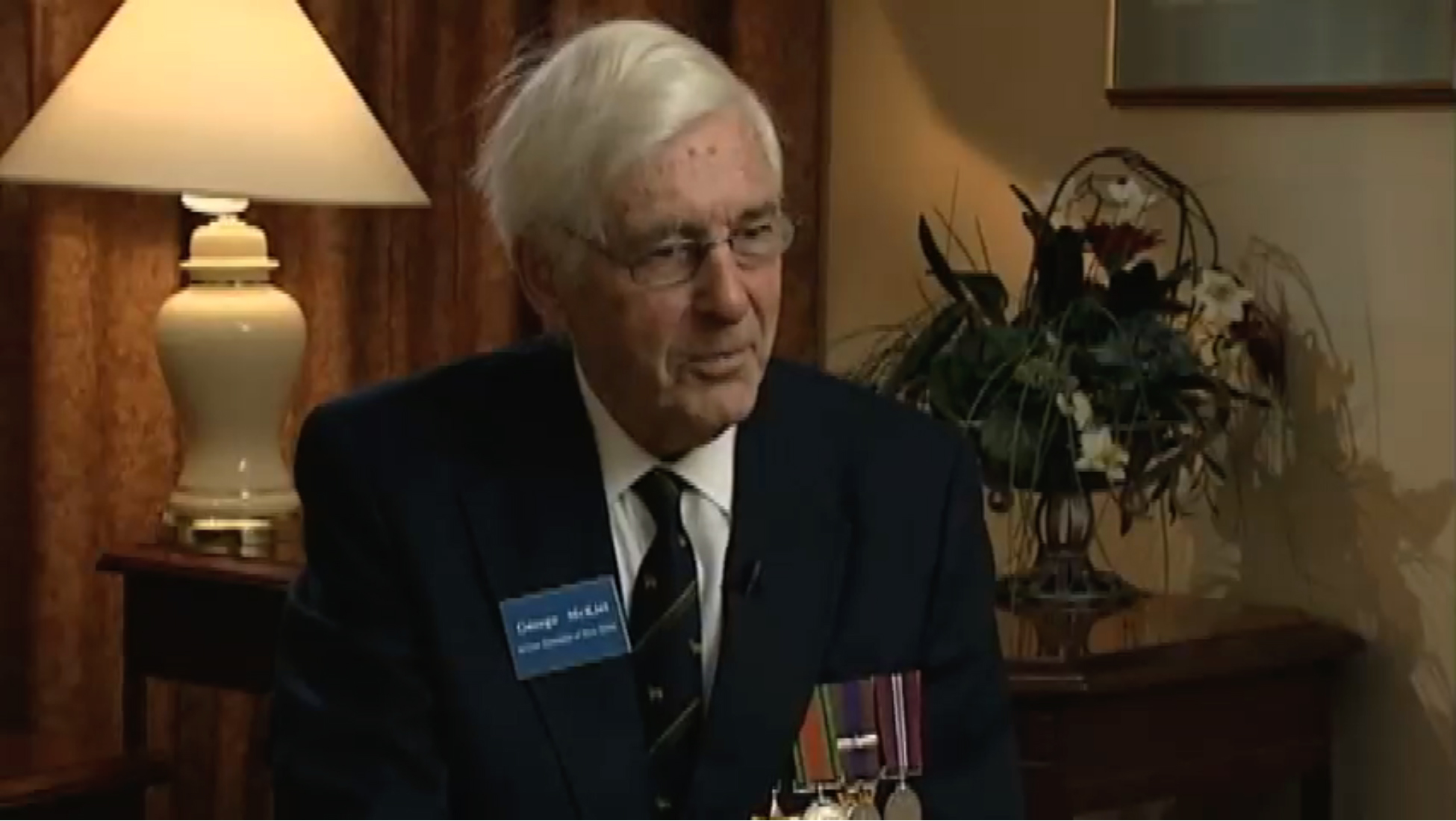

a little game. Would you, would you like to be part of it, George

as a newcomer, because he won't know you?" And I said,

"Be a part of what kind of a game?" He said, "Well, just to go

and, and see what he tells you and then maybe we'll have some

ammunition so he can mix in a little better with the rest of us."

Well, I went along with it and they came back and handed me

a group captain's jacket, battledress jacket, with DFC and bar

plus a DSO, and so I was outranking the New Zealand officer.

And he called me down, he had a little small room at the end

of the barrack lot, and said, "You know, McKiel, some of these

people have been here since 1939. Some of them are, are very

experienced, and you can learn a great deal from them.

I suggest the first thing you do is to take down your decorations

and your rank and try and mix in and learn through the basics

of the camp." And we chatted a bit more. I went back to our room

and told the New Zealanders what had happened, and they were

rolling on the floor. They were just delighted. "It worked!

It worked! We can humble this guy and get him to be one of us."

Anyway, we sort of overstepped the mark on that because he

invited me back a day or two later and said, "We need another

talk, McKiel." I said, "Good." And when we started chatting,

he said, "You know, there's a lot happening here in camp.

It looks as though there's not a great deal, but there's a lot

of secret work going on and I, I should really tell you a little

bit about this, so that you know that you're part of this now."

However, when I was chatting with the wing commander, he said,

"Now, one of the things you should recognize, McKiel, is that

we do have a tunnelling going on." I said, "Oh?" And he said,

"Yes. In fact, it's only 12 feet from your bunk, where the

entrance is." He said, "I'll just take you to that room and show

you what the trap is like, so that you can have some idea of the

ingenuity that went into designing it." Well, it was a small

stove, wood stove, coal stove, that was in this, on this block

of bricks and tile in the room, and they could lift the stove up

with a couple of two by fours off to one side, leave the chimney

connected so that if the fire was going it would still be okay,

and there was the entrance to the tunnel. And the hut was

supported on these brick pillars, and they had drilled a way down

through the bricks and then had a ladder which went down 30 feet

into the sand. The problem, apparently, was that the Germans had,

when they built the camps, said, "We're going to make this

totally impossible for anybody to escape from," and, so, amongst

other things, they planted monitors in the ground to detect any

sort of chance of tunnelling or digging. They were convinced

that there was some activity going on, because when you get

thirty feet down, the sand, it was all sand you saw, the soil was

totally different. It was a lighter colour, and there was a

particular smell which the German guard dogs could pick up on.

So, although we had the ability to dig with our spoons and

implements at the face of the tunnel, it meant that sand disposal

was a top priority. How to get rid of it without the Germans

realizing that we were doing it. And one of the ways of doing

that was we created people that we called "penguins", and the

penguins were equipped with bags that went down the inside of

the trousers with a drawstring at the end so you could pull on

the cord and then the sand would dump out. And then we could

scuff it into gardens, or sports field, or whatever, where it

wouldn't perhaps be picked up. They also tried putting some up

in the, up in the rafters of the huts, but after a fall-in that

brought the sand all crashing down, they abandoned that.