Canada Remembers Times - 2012 Edition - Page 2

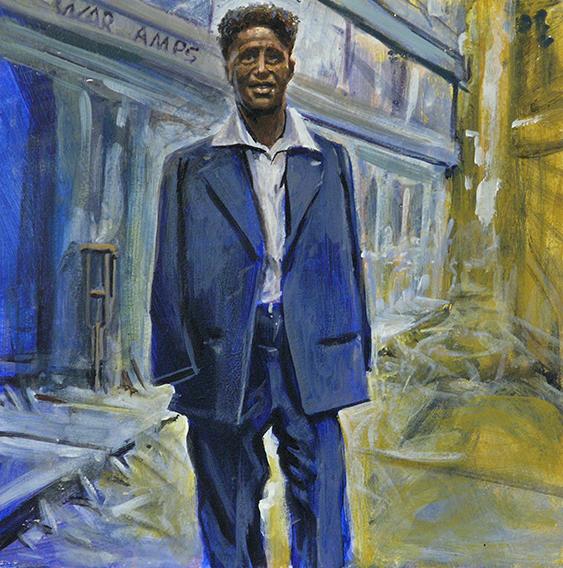

The Canadian Forces in the Congo

Canadian soldier at a Congolese defensive position in 1963.

Photo: DND UNC63-23-9

One of the most challenging missions ever faced by Canadian peacekeepers was the United Nations (UN) effort in the Congo from 1960 to 1964. This large African country had been a Belgian colony for 90 years before gaining its independence in 1960. Unfortunately, the new nation was immediately plunged into chaos as a result of the political in-fighting, inter-tribal tensions, famine, mutiny by the army, international interference and the widespread violence that ensued.

The UN soon sent in peacekeepers to try to restore order and stability. It was a major undertaking—eventually a UN force of more than 20,000 personnel would serve in the country, including more than 300 Canadians. The UN troops found themselves in a new kind of peace support mission. Violence and weapons were everywhere, but they were able to prevent break-away portions of the country from splitting off. They also helped push out foreign mercenaries who were contributing to the instability. In the end, however, the UN forces were not enough to stop the greater forces of upheaval rocking the Congo and they departed in 1964. Two Canadian soldiers died during that mission.

Sadly, the situation in the Congo has remained troubled and Canadian Forces members have again been serving in the country since the late 1990s to try to improve the situation.

Remembering the South African War

Canadians on the veldt in South Africa.

Photo: CWM 19820205-003. © Canadian War Museum

The year 2012 marks the 110th anniversary of the end of the South African War—the first time that large numbers of Canadian soldiers served overseas.

Our young country sent troops to South Africa in 1899 to help Britain put down an uprising by Dutch settlers and bring the entire region under its control. Fighting so far from home in such an unfamiliar setting was very challenging. The Canadians, however, soon earned a reputation for skill and tenacity in the Battle of Paardeberg and the Battle of Leliefontein. During the war, five Canadians earned the Victoria Cross, the highest award for military valour.

The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging on May 31, 1902. The Dutch settlers surrendered their independence in exchange for aid to those affected by the fighting and for eventual self-government. By the end of the conflict, more than 7,000 Canadians had volunteered for service with approximately 280 losing their lives (most from injury or disease caused by the harsh conditions) and more than 250 being wounded.

‘Hard-Over’ Harry

DeWolf on the bridge of HMCS Haida in 1944.

Photo: LAC PA-134298

Henry “Harry” DeWolf was born in Nova Scotia in 1903. He became the most decorated Canadian naval officer of the Second World War. Under his command, HMCS Haida earned the reputation as the “fightingest ship in the Canadian Navy.” It was responsible for sinking 14 enemy ships in just over a year. Many of the battles took place at night in the English Channel, when DeWolf secured his reputation as a fearless and skillful tactician. He was known to his crew as “Hard-Over Harry” for various bold maneuvers off the coast of France (the nautical term ‘hard over’ means to turn the ship’s wheel sharply).

During the post-war years, Captain DeWolf commanded the aircraft carriers HMCS Warrior and HMCS Magnificent. He died in 2000, at the age of 97, and was buried at sea. There is now a waterfront park named after DeWolf on the Bedford Basin in Nova Scotia.

The First Ukrainian-Canadian General

Brigadier-General Joseph Romanow.

Photo courtesy of Mary Romanow.

Joseph Romanow was born in Saskatoon in 1921. One of many Ukrainian-Canadians to volunteer during the Second World War, Romanow joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in 1940. He first saw action piloting in anti-submarine (U-boat) air patrols and escorting convoys. After a short stint in England, he was transferred to Burma where he flew Dakota DC-3 transport planes and dodged Japanese fighter aircraft. While in Asia, he helped train Gurkha soldiers and served with them.

After the war, Romanow played a role in helping bring more than 35,000 Ukrainian refugees to safety in Canada.

In the post-war years, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering. Romanow then rejoined the RCAF and earned a master’s in aeronautical engineering. He would later work on the Avro Arrow jet program and was the officer responsible for the final installation and operation of Canada’s first nuclear missile site in North Bay, Ontario.

In the early 1970s, Romanow spent three years in West Germany helping NATO reorganize its air command structure.

The first Ukrainian-Canadian to become a general in the Canadian Forces, he died in Ottawa, in 2011, at the age of 89.

The War of 1812

Tensions between the United States (U.S.) and Great Britain had been growing over economic and political issues for some time when the U.S. declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812. The fighting would primarily take place in the continental U.S. and in Upper and Lower Canada. Naval battles also occurred on the Great Lakes and the Atlantic coast.

Although preoccupied with their conflict with France in Europe, the British managed to repel several U.S. intrusions into Upper and Lower Canada with the help of their loyal Aboriginal allies and the Canadian militias. The battles of Queenston Heights, Lundy’s Lane, Crysler’s Farm and Chateauguay were some of the key events of the war. In April 1813, the Americans attacked York (present-day Toronto), where they burned the Parliament buildings.

After Napoleon’s fall in 1814, the British were able to focus their attention on the fighting in North America and send three large armies to the continent. British forces attacked Washington, D.C., and burned the White House in August 1814.

After years of fighting, both sides were tired of paying taxes to sustain a war that was going nowhere, and merchants clamoured for the resumption of trade. Peace negotiations began in late 1814 with the Treaty of Ghent ending the war on February 17, 1815. The results . . . almost 4,000 soldiers killed in action and both sides claiming victory.

The Will to Live

Curley Christian after the war.

Image: Military Museums Mural of Honour

(courtesy of the Military Museums).

Ethelbert “Curley” Christian was born in the United States in 1882 and he settled in Ontario as a young man. He volunteered for the army during the First World War, one of the many brave Black Canadians who did so.

On April 9, 1917, Curley Christian was serving with the Winnipeg Grenadiers during the Battle of Vimy Ridge when artillery fire buried him in a trench. All four limbs were crushed by debris and the wounded soldier was trapped for two days. Found barely alive, he cheated death again when two of his stretcher-bearers were killed by enemy fire while carrying him from the battlefield.

Curley Christian miraculously survived but unfortunately gangrene set in and doctors had to amputate his arms and legs. His positive demeanor remained, however, and he would go on to marry, become a father and live a long and active life until his death in 1954. He is the only Canadian quadruple amputee to survive the First World War.

- Date modified: