Canada Remembers Times - 2018 Edition - Page 2

A French-Canadian tragedy at Chérisy

Sketch of Major Georges Vanier by war artist Alfred Bastien and photo.

Images: Library and Archives Canada PA-166146 and PA-002777

By the onset of the Last Hundred Days of the First World War, the 22nd Battalion-Canada’s only frontline Francophone unit-had been through a lot. As was the case with other battalions after four long years of war, many of its members had become casualties and their replacements had little combat experience. This did not stop them from seeing heavy action at the French village of Chérisy on August 27 and 28, 1918.

Some 700 men of the battalion had been ordered to advance in broad daylight, into the heart of a fortified German line. Caught in the middle of heavy machine gun fire and exposed to a shower of shells, the 22nd Battalion suffered heavy losses. More than 100 of its men were killed and 200 wounded during the battle. All of the unit’s officers were killed or wounded, including Major Georges Vanier. He lost a leg but later went on to become Canada’s first Francophone Governor General. The battalion had little time to recuperate before returning again to the front lines in September to help the Allies to victory in the closing weeks of the First World War.

A brush with the Korean War

Freeze – Patrol Under Enemy Flare, painted by Ted Zuber.

Image: Beaverbrook Collection of War Art CWM 19890328-012

There is a long tradition of capturing war experiences through art. Although official war artists were commissioned by Canada in the First and Second World Wars, this was not the case in the Korean War. But that did not stop Private Ted Zuber from using his sketchbook to capture what he saw while serving with The Royal Canadian Regiment in Korea.

The sketches later inspired him to create paintings about the Canadians’ wartime experiences there. Zuber also talked to other Veterans and studied aerial photographs, maps, and war diaries to help him paint the Korean War. Many of his works are now at the Canadian War Museum.

Each painting tells a different story. Whether it is capturing the emotions on our soldiers’ faces during a battle, the rugged Korean landscape, or a quiet moment on the front lines, Zuber offers a vision of what life was like during the conflict.

The painting shown here depicts a tense moment where Canadian soldiers on patrol are caught in the open as an enemy flare lights up the sky. It was featured on special street banners in our nation’s capital this year to commemorate the 65th anniversary of the Korean War Armistice.

Flowers for freedom

The Price of Peace monument in Ortona.

Photo: Veterans Affairs Canada

During the Second World War, Canadian soldiers were involved in a grim battle that took place in Ortona, Italy. It began on December 20, 1943, and lasted for eight bloody days. The streets of the German-occupied town were a war zone. After a week of vicious fighting, the Canadians were victorious and Ortona was liberated, but sadly some 213 of our soldiers lost their lives.

Today, the town has been rebuilt and little evidence of the war remains, but the Italian people have never forgotten the Canadians who had helped them, including sisters Francesca and Maria LaSorda. In 1943, the girls were hiding with their family in a cramped, cold barn in Ortona when they met some of the Canadians. The girls offered to wash their clothes and our kind soldiers gave them some much-needed food in return.

Years later, the sisters found a lovely way to show their appreciation. In October 1999, a monument called the Price of Peace was unveiled in Ortona to honour the liberators. It depicts a wounded Canadian soldier being comforted by a comrade kneeling at his side. The LaSordas attended the ceremony and watched as flowers were placed on the memorial. When the flowers wilted, they volunteered to replace them with fresh ones. Together, they performed this tenderhearted gesture for approximately 15 years until one sister died. What an act of remembrance!

A silenced gun comes home

The King and Queen of the Belgians offered a unique gift of remembrance during their state visit to Canada in March 2018. This special delivery, a 4.5-inch howitzer, was one of the last Canadian artillery guns to fire during the Great War on November 11, 1918. The piece was donated to the city of Mons, Belgium, in August 1919 by the Commander of the Canadian Corps, Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie. This powerful reminder of the silencing of the guns is now on loan to the Canadian War Museum as a part of a special exhibit marking the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War.

Life and death on the high seas

The tough RCN warships known as corvettes escorted hundreds of convoys during the Second World War.

Photo: Library and Archives Canada PA-4950909

The Battle of the Atlantic lasted from the first day of the Second World War in September 1939 to the end of the fighting in Europe in May 1945. It pitted the Allies, who wanted to transport supplies and troops to Europe where they could be used in the fighting, against the Germans who wanted to sever this vital lifeline.

It was a hard fought struggle in which the German U-boats (submarines) came dangerously close to victory at sea as they torpedoed hundreds of Allied transport ships in the opening years of the war. With the adoption of new technology and tactics, however, 1943 saw the changing of the tide as the Allies finally gained the upper hand.

Members of the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), Canadian Merchant Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) played leading roles in the Allied war at sea. Indeed, more than 25,000 Allied merchant ships safely made it across the Atlantic Ocean during the war under Canadian escort, delivering approximately 165 million tons of valuable materials to Europe. The cost of helping the Allied convoys get through was high-some 2,000 RCN sailors died during the conflict, 750 RCAF airmen were lost over the Atlantic and more than 1,600 merchant seamen from Canada and Newfoundland were killed. But without victory in the Battle of the Atlantic, the Allies could not have triumphed in the Second World War.

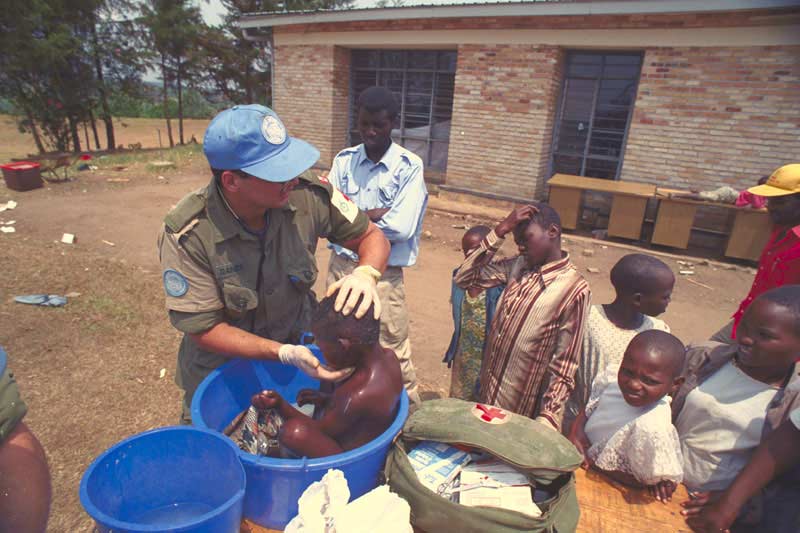

The Canadian Armed Forces in Rwanda

Canadian soldier offering aid to young children in Rwanda.

Photo: Department of National Defence

One of Canada’s most challenging international peace support efforts took place in the central African country of Rwanda from 1993 to 1996. The people of Rwanda predominately come from two tribes, the Hutus and the Tutsis. Their relations had been strained for centuries, but in the early 1990s tensions flared dramatically and the situation moved toward full-scale civil war. In response, the United Nations undertook peace missions there, the largest being the UN

Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) in which Canadian Armed Forces members played a leading role.

Even with these peacekeepers deployed, the bad situation in the country turned into a nightmare in April 1994. The Hutus began to massacre hundreds of thousands of Tutsis and moderate Hutus. The UN soldiers did what they could in this chaotic environment of widespread killing and mayhem, but they were too few in number and constrained by their limited mandate. They were able to save some people, but in the end they could not prevent the worst of the horrific violence. Canadian Armed Forces members remained in Rwanda after the genocide to help with humanitarian efforts, mine clearing and refugee resettlement before leaving the country in 1996.

The wounds of peacekeeping service are not always obvious physical ones. Witnessing human brutality of the most horrific kind can have a profound impact and this has been one of the harshest legacies of Canada’s efforts in Rwanda. Many of our Veterans who served there developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a psychological condition that can have serious and long-lasting impacts.

Did you know?

George Lawrence Price.

Photo: CVWM

The last Canadian to fall in combat during the First World War was 25-year-old Private George Price of Saskatchewan. Sadly, he was killed by a sniper’s bullet near Mons, Belgium, just two minutes before the Armistice went into effect at 11:00 a.m. on November 11, 1918.

- Date modified: