Canada Remembers Times - 2017 Edition - Page 4

Yukoners rush to serve

Yukoners posing with one of their machine guns.

Photo: Library and Archives Canada 3397590

The First World War began in August 1914 and many volunteers quickly flocked to recruiting stations across the country. It was a remarkable national response and Canadians in the north wanted to be part of the action too. Some 50 residents of the Yukon soon joined a unit that would become known as the Yukon Motor Machine Gun Battery. Its men left Dawson City in June 1915 and eventually proceeded overseas where they trained in England for some time while waiting to be fully equipped for service on the front lines. They were finally sent to the Western Front in the late summer of 1916.

The Yukon machine gunners would see heavy action throughout the rest of the conflict, including fighting at the Somme, Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele, Amiens and the Canal du Nord. Its original ranks greatly reduced by combat casualties, the survivors were eventually combined with other units to keep going. The men’s fortitude was unquestionable and it was said that, by the end of the war, every officer in the Yukon battery had received medals for their great courage.

Rosalie's incredible journey

Detail of the engravings on Henri Lecorre’s Lee-Enfield rifle Rosalie.

Photo: Vincent Royer, courtesy of the Musée Royal 22e Régiment

Rosalie was a unique First World War weapon. The rifle belonged to Henri-Paul Lecorre, who had volunteered with the 22nd French-Canadian Battalion in Montréal in April 1915.

Lecorre used a pocket knife to carve the names of the battles in which his battalion participated on “Rosalie,” the nickname he had affectionately given his rifle. As it was strictly forbidden to damage military equipment, Rosalie was confiscated and orders given to destroy it. To protect Rosalie, Lecorre quickly carved a second rifle and swapped it for his precious weapon.

In June 1918, Lecorre was fighting near Neuville-Vitasse, France, when he was wounded during a gas attack. He was evacuated to a military hospital and then sent home, but Rosalie was left behind on the muddy battlefield.

Rosalie was later recovered and sent back to the rifle factory in England to be inspected, where an employee decided to preserve the unique-looking weapon. A few years later, during the Second World War, a Canadian general was visiting the same factory and noticed the distinctive carvings. He arranged for Rosalie to be sent to the Royal 22e Régiment headquarters in Quebec, where it was put on display in their military museum.

The rifle’s origin remained a mystery until October 1956, when Lecorre and his wife amazingly spotted it in a travelling exhibit. It had taken 38 years, but Lecorre and Rosalie were finally reunited. Today, Rosalie is proudly displayed in La Citadelle de Québec.

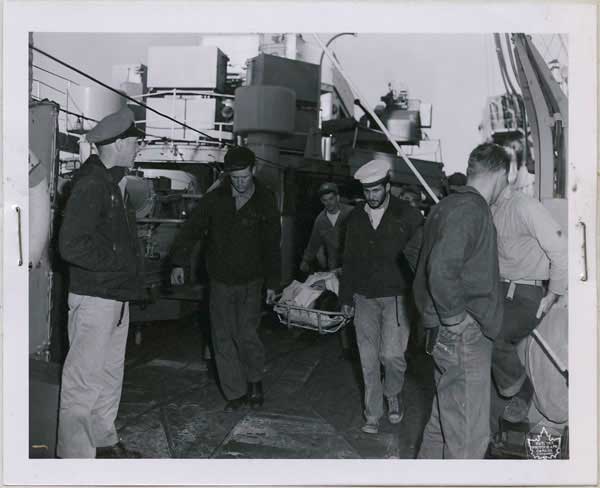

Under fire in Korea

Wounded sailor being taken for medical treatment after HMCS Iroquois was hit.

Photo: Library and Archives Canada 3928696

Canadians served on land, at sea and in the air during the Korean War. As part of these efforts, a total of eight Royal Canadian Navy destroyers served in the waters of the Far East at different times during the course of the conflict.

One of our sailors’ tasks was shelling enemy shore targets, including the rail lines that ran close to Korea’s eastern coast. The ships of the United Nations fleet that scored hits on these tempting but elusive targets were said to be part of the “Trainbusters Club.”

It could be dangerous duty, as sadly proved true for HMCS Iroquois on October 2, 1952. The destroyer was exchanging fire with an enemy gun battery on shore that day when it took a direct hit, killing three Canadian sailors and wounding ten. It was our navy’s only combat-related deaths of the Korean War.

HMCS Assiniboine's daring attack

Crew of HMCS Assiniboine and their mascot soon after sinking a German submarine in 1942.

Photo: Library and Archives Canada PA-204349

During the Second World War, Allied and German forces struggled for control of the Atlantic Ocean. This clash was known as the “Battle of the Atlantic” and lasted for the duration of the war in Europe, from September 1939 to May 1945. Allied merchant ships that carried the troops and provisions were vulnerable to attacks by preying German submarines called “U-boats.” Our navy provided armed escorts across the Atlantic Ocean to protect the convoys.

On August 5, 1942, the Canadian destroyer HMCS Assiniboine was leading merchant ships travelling from Sydney, Nova Scotia, to the United Kingdom. When one of the ships was torpedoed, HMCS Assiniboine went chasing after the attackers.

After a long and nerve-wracking hunt in the fog, the Assiniboine spotted the German submarine U-210. A high-speed chase and exchange of heavy gun fire ensued, culminating with the destroyer daringly ramming the German vessel just as it was submerging. The submarine began to take on water and resurfaced, allowing the Assiniboine to strike again and finally sink it. Sadly, HMCS Assiniboine lost one crew member, but the ship managed to rescue 37 German submariners.

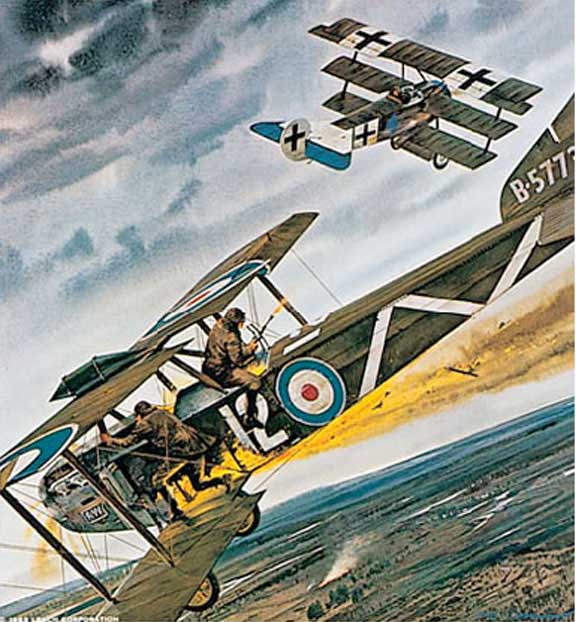

Born to Fly

Painting by Merv Corning depicting the heroic actions of Alan McLeod.

Image via Canadian Aviation Historical Society and Leach Heritage of the Air Collection, 1963

Alan McLeod was only 18 years old when he left his hometown of Stonewall, Manitoba, to join the Royal Flying Corps, graduating from his training with flying colours. While serving in the skies over the Western Front during the First World War, Lieutenant McLeod performed an amazing feat on March 27, 1918, which made him one of the youngest recipients to receive our highest military honour, the Victoria Cross.

McLeod and his flying partner, Lieutenant Arthur Hammond, were in the air over Albert, France, when they were attacked by eight German fighter planes. Hammond shot down three of the enemy aircraft but not before their own plane was hit and caught fire, with both airmen being badly wounded. Reacting swiftly, McLeod managed to climb out onto the left wing in order to tip the plane and keep the flames away from the trapped Hammond.

After their crash landing in No Man’s Land, McLeod was wounded again while bringing his partner to safety. The pair had to take cover in a shell hole for several hours before being rescued by Allied soldiers. Sadly, after several months of recovery back in Canada, and still weakened by the ordeal, McLeod died of the Spanish Flu, just five days before the end of the war.

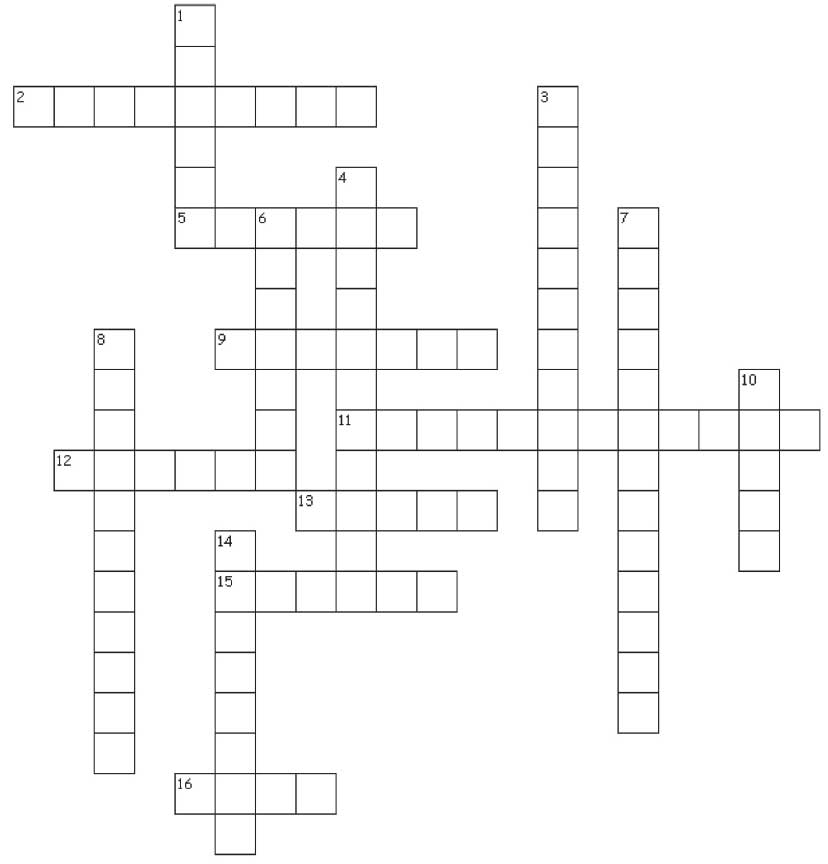

Crossword Puzzle

Did you read the newspaper stories carefully? All the answers to the crossword clues are found in the newspaper.

Across

- 2. Manitoba hometown of heroic First World War pilot Lieutenant Alan McLeod.

- 5. Last name of general who commanded the Canadian Corps at Hill 70.

- 9. Nova Scotia city where a tragic explosion occurred on December 6, 1917.

- 11. Home province of Louis Arcand, who served in both the First and Second World Wars.

- 12. French seaside town that was the main objective of an August 1942 raid.

- 13. Last name of war artist who created a painting of Canadians in action at Hill 355.

- 15. Last name of the 1964 Silver Cross mother who lost three sons in the Second World War.

- 16. Name of ridge in France where Canadians fought in April 1917.

Down

- 1. Home province of Lawrence Rogers who died with a teddy bear in his pocket.

- 3. Country where more than 40,000 Canadian Armed Forces members served 2001 - 2014.

- 4. Ontario city where the Trooper Marc Diab Memorial Park was unveiled in 2010.

- 6. Nickname of Canadian soldier Henri-Paul Lecorre’s unique First World War rifle.

- 7. Battle in Belgium where Canadians saw heavy action in the fall of 1917.

- 8. Name of Canadian destroyer that sank a German submarine on August 5, 1942.

- 10. Last name of a Sikh-Canadian soldier who was wounded at Vimy Ridge.

- 14. Name of Canadian destroyer hit by enemy shellfire during the Korean War.

- Date modified: