4.1 Effectiveness

Performance measurement monitors the progress of programs towards their expected resultsFootnote 30. A Performance Measurement Strategy (PMS) is used to regularly measure key indicators and results. This information can be used to compare achieved results to expectations and to assist in measuring the effectiveness and success of a program. A program Performance Measurement Plan (PMP) and a program logic model (see Appendix A), are tools that support the PMS. These tools have been developed for the Program and were analyzed by the evaluation team.

A logic model serves as a program’s road mapFootnote 31. The model outlines the intended results (outcomes) of the program, illustrates key activities the program will undertake, and the outputsFootnote 32 those activities intend to produce in achieving the expected outcomes. Although there are various factors or programs beyond the Department’s control, the conclusion is that if individuals have access to home care and support services, then their needs will be metFootnote 33.

Program outcomes are the changes or differences that result from program activities and outputs. Outcomes are described as immediate, intermediate, or ultimate based on the contribution/influence the program has on each outcome. As outlined by the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) guideline, Supporting Effective Evaluations: A Guide to Developing Performance Measurement Strategies:

- immediate outcome(s) should equate to a “change in awareness, knowledge or skill”;

- intermediate outcome(s) should equate to a “change in the target population’s behavior”; and

- ultimate outcome(s) should equate to a “change of state in a target population”Footnote 34.

When the above outcomes are met, the Program contributes to the Department’s Strategic Outcome #1: financial, physical, and mental well-being of eligible Veterans (as shown in the PAA). The evaluation team found that although the tools to measure the outcomes have been established, reports required to accurately measure program success are currently not available.

Immediate Outcome: Eligible individuals have access to home care and support services.

The performance indicators of the immediate outcome for the Program must be revised to better measure outcome achievement.

The program logic is straightforward; the program provides those eligible with access to services. Section 3.1 gives an overview of these recipients and provides an indication of the recipient groups accessing the program annually.

The PMP indicates the immediate outcome is measured in two ways:

- An individual is eligible therefore he/she has access to Program services, measured by:

- number of recipients who are eligible for the Program;

- percentage of eligible recipients who received a payment or grant for Program services;

- number and percentage of VIP appeals received, by level, number approved, and number declined.

- An individual can access services, measured by:

- percentage of eligible Program recipients living at home who report they are able to find people to provide the Program services they need.

The immediate outcome is the outcome over which the program has the most control. VAC controls eligibility to the program and the disbursement of benefits. However, the program does not control the availability of service providers as outlined in (b) above.

The evaluation team is of the opinion that the performance indicators for the immediate outcome of the program must be revised to reflect results over which the Department has control. The PMP and PMS measures must be modified to reflect the achievement of the immediate outcome and reported upon accordingly.

Intermediate Outcome: Eligible individuals’ needs for homecare and support are met.

The intermediate outcome for the Program is being met.

The last National Client Survey (conducted in 2010) reported that 86% of Program recipients said the Program "meets their needs"Footnote 35. Interviews with VAC staff and the Processor indicate that mostFootnote 36 interviewees feel that recipients’ needs are being met. This is further supported by the file review of the VIP follow-up which shows that 83% of recipients state the program meets their needs. The OVO noted in an interview that recipients have few concerns with the program and that Program files do not constitute a major workload for OVO staff.

Staff indicated in interviews that recipients have varying opinions on the introduction of the VIP grant payment. Staff noted some recipients are confused about the purpose of the money received, while others feel that with the introduction of the grant, they are now receiving less money. However, the findings of a file review conducted by the evaluation team show that since the implementation of the GDT, 92% of Veterans have been grandfathered in at their previous actual amount spent for Program services, or are now receiving more as a result of the GDT. For the 8% of Veterans who receive less since the implementation of the GDT, it was most often due to changes in the Veteran’s circumstances (e.g. change of address, living arrangements, etc.). Therefore, the change from a contribution to a grant did not negatively impact recipients financially and it is reasonable to assume the program continues to meet their needs.

In addition, a statistically valid file review was conducted by the evaluation team to determine if survivors/primary caregivers were negatively affected by the introduction of the grant. The file review determined that survivors and primary caregivers are assessed on their own needs after the Veteran passes and that approximately 50% received more than the Veteran did prior to the implementation of the grant, and 50% received less or did not changeFootnote 37.

Ultimate Outcome: Eligible individuals are able to remain in their own homes and communities.

The ultimate outcome for the Program is being met.

The objective of the Program is “to provide financial compensation to eligible Veterans and other clients so that they receive the home care and support services they need to remain independent in their homes and communities…”.Footnote 38 The ultimate outcome is achieved if the Program contributes to recipients’ ability to live independently in their homes and communities longer.

VAC measures the ultimate outcome based on: the percentage of Program recipients who report reliance on the Program to allow them to remain at home; and, the rate of admissions of recipients to nursing homes. VAC’s 2010 National Client Survey shows that 92% of those in receipt of Program benefits agreed that "they rely on the VIP services received to help them remain in their homes and community”.Footnote 39 Interviews with VAC staff confirmed most interviewees felt that the program allowed recipients to stay in their homes.

This was further supported by the Evaluation of the Veterans Independence Program (2011) which found that “Those receiving their first intermediate care payment … show that the majority of recipients (84%) began VIP with home care elements, and had on average a two year delay in institutionalization compared to their counterparts who enter VIP directly through intermediate care".Footnote 40

4.2 Economy and Efficiency

Program expenditures remained relatively constant.

There were 96,722 Program recipients in 2014-15, including primary caregivers and survivors. Recipients are forecasted to decrease to approximately 79,900 by 2019-20 (see Table 4).Footnote 41

| VIP Recipients | Forecast | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | |

| Veterans | 57,300 | 54,800 | 52,300 | 50,100 | 48,300 |

| War Service | 27,600 | 23,500 | 19,500 | 16,000 | 12,800 |

| Canadian Armed Forces | 29,700 | 31,300 | 32,700 | 34,100 | 35,400 |

| Survivors | 36,900 | 35,900 | 34,600 | 33,200 | 31,600 |

| Total VIP Recipients | 94,200 | 90,600 | 86,900 | 83,300 | 79,900 |

Expenditures are forecasted to decrease as recipient numbers decline (see Table 5).

| VIP Expenditures ($millions) | Forecast | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | |

| Ambulatory Care | $0.7 | $0.7 | $0.6 | $0.6 | $0.6 |

| Health and Support Services | $0.4 | $0.4 | $0.4 | $0.4 | $0.4 |

| Access to Nutrition | $7.1 | $6.7 | $6.2 | $5.8 | $5.4 |

| Personal Care | $24.1 | $22.8 | $21.2 | $19.7 | $18.4 |

| Social Transportation | $1.1 | $1.0 | $0.9 | $0.7 | $0.6 |

| Home Adaptations | $0.6 | $0.6 | $0.6 | $0.6 | $0.6 |

| Adult Residential Care | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 |

| Intermediate Care | $51.8 | $49.9 | $47.1 | $44.5 | $42.3 |

| Total Contributions | $85.9 | $82.1 | $77.0 | $72.3 | $68.3 |

| Housekeeping (Grants) | $220.4 | $215.8 | $210.4 | $205.0 | $199.9 |

| Grounds Maintenance (Grants) | $59.6 | $59.7 | $59.7 | $59.7 | $59.8 |

| Total Grants | $280.0 | $275.5 | $270.1 | $264.7 | $259.7 |

| Total VIP | $365.9 | $357.5 | $347.1 | $337.1 | $328.0 |

To determine the overall cost of the Program, program resource utilization costs are included. These costs are associated with program delivery and include items such as salaries, overhead, employee benefits, and contract administration costs. The current method of apportioning costs to an individual program hinges on an allocation model that looks at the administrative cost for each work unit. An estimation is then made to determine what percentage of the total administration cost should be charged to each program/subprogram.

The Department has recognized that the allocation model used during the period of the evaluation may not provide an accurate representation of administration costs; therefore, a new model is being introduced for fiscal year 2015-16 (outside the period of the evaluation). The new model will use key staff positions to determine the percentage of administrative costs attributable to each program/subprogram instead of using work units.

Though the allocation model used during the period of the evaluation may not provide an exact depiction of administration costs, the model is useful, when applied consistently, for determining program administrative cost trends. For consistency, the same tool was utilized throughout the five-year period under review. The allocation model for the Program reveals that administrative costs were approximately 12.3% of total program costs for fiscal year 2014-15. Overall costs have trended downward from a high of 18% in 2011-12 (see Figure 2 for more details).Footnote 43

Figure 2 – Administration Expenses as a Percentage of Total Costs

Figure 2 – Administration Expenses as a Percentage of Total Costs

| 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18.00% | 14.71% | 12.15% | 12.29% |

The evaluation team researched international Veterans programming to compare administrative costs with VAC’s Program and to identify opportunities for improvement in delivery. However, it was difficult to make a direct comparison as each organization operates differently.

The evaluation team also reviewed provincial organizations providing home care services to compare administration expenses to VAC’s Program. While several provinces were found to have a higher administration-to-program cost ratio than VAC, additional elements were included in provincial administration costs. For example, the administrative costs in the provinces of Ontario and Prince Edward Island include the cost of provincial staff who provide home care service. VAC does not does incur administration costs associated with service provision since Program services are provided by individuals and private companies hired by Program recipients. Because of the different program models used, the evaluation team could not directly compare costs of similar programs.

The evaluation also looked at duplication within the administration of the Program. A business requirements document outlines the role of VAC and the Processor. A review of the business processes and interviews with VAC staff and Processor staff confirm that roles are clearly understood. No evidence was found by the evaluation team to identify significant areas of redundancy or duplication within the internal administration of the Program.

No issues were identified with the timeliness of Program decisions.

The Program does not have a service standard in place for processing applications. The evaluation team conducted a small sequential samplingFootnote 44 file review to look at the timeliness of decisions and no substantial issues were identified. This finding was further supported by staff and OVO interviews which did not highlight any issues with the timeliness of Program decisions. Improvements to the tracking of Program applications are expected to be implemented through system enhancements in the upcoming fiscal year (2016-17). It is anticipated that this will provide information to inform the Department of the timeliness of decisions.

Program costs must be tracked and reported on in order to accurately measure program efficiencies.

Treasury Board defines efficiency as “…the extent to which resources are used such that a greater level of output is produced with the same level of input or, a lower level of input is used to produce the same level of output. The level of input and output could be increases or decreases in quantity, quality, or both.”Footnote 45 At the time of the evaluation, VAC did not have the capability to accurately measure the full cost of its individual outputs, as found in the logic model. This lack of capability was confirmed through consultations with the program area. The lack of available measures makes it difficult to determine the efficiency of Program changes.

For example, the Department is currently developing a new interface for the Program which will allow VAC and the Processor to update electronic records in real time. The objective of this initiative is to increase efficiencies (e.g., there will be a shorter wait time for records to update, less data entry required, fewer chances for human data entry errors, and added tracking capabilities, etc.). Currently, there is no accurate Departmental information available on input costs (time, system, staff, etc.); therefore efficiencies of changes/modifications cannot be measured.

Program Payment Model: Contribution to Grant

Available data is not sufficient to evaluate the efficiency of the new Program payment model.

Since the last evaluation, the Department has changed the housekeeping and grounds maintenance payment model for the Program from a contribution to a grant. Prior to 2013, benefit recipients were responsible for submitting receipts to the Department for reimbursement of monies spent on service providers. In January 2013, the Department began issuing semi-annual, up-front grants to eligible benefit recipients to compensate for future monies spent on service providers.

A lack of data makes it difficult to determine if the change from a contribution to a grant is efficient. Research has not been conducted by VAC since the implementation of the grant to determine if recipients find the new payment method more efficient. However, secondary information, gathered from staff and file reviews, indicates that there has been no negative effect on the Program.

In the absence of costing data, the team looked at Program operational efficiencies.Footnote 46 As outlined in the Program’s logic model, one of the program outputs is a benefit arrangement. The GDT is the main tool used to develop the benefit arrangement. As such, the tool was examined to determine if it was efficient. As a result of the examination, an unintended outcome was identified as shown in Section 4.3.

4.3 Unintended Outcomes

Grant Determination Tool (GDT) used for Calculating Grant Amounts

The GDT requires refinement to allow for a greater range of service hours for Veterans with moderate needs.

The GDT is a worksheet developed to assist with the calculation of grants for housekeeping and grounds maintenance. The tool was designed to ensure consistency, accuracy, and fairness when determining an individual’s level of need for services. The GDT is used by both VAC and the Processor:

- VAC staff administer the initial GDT to new recipients with Program eligibility and to recipients who contact VAC indicating there has been a change in their needs. The initial GDT is completed based on information gathered from completed assessment tools such as the Regina Risk Indicator Tool (RRIT)Footnote 47, screenings, and assessments.

- The Processor administers the GDT for recipients when a change in need is identified during a telephone follow-up. The Processor relies solely on the GDT and does not create or use the additional assessment tools which assist VAC staff in the administration of the GDT. If the Processor feels the use of additional tools is warranted, procedures are in place to refer the case to the appropriate VAC Area Office.

The administrator of the GDT asks the recipient a series of questions about their housekeeping and grounds maintenance needs, such as meal preparation, laundry, errands, or snow removal. Based on the recipient’s responses, the GDT calculates a level of need score for housekeeping which ranges from 0.5 - 6.5+. This score is then translated into a range of housekeeping hours allotted. The tool also calculates a total grounds maintenance amount for eligible recipients.

The evaluation team reviewed the business processes used by VAC and the Processor for administering the GDT. The evaluation team also interviewed VAC and Processor staff who used the tool, and observed the delivery of the GDT. In addition, the team studied the GDT in a test environment and ran scenarios through the tool to evaluate its consistency and to test any anomalies identified during interviews.

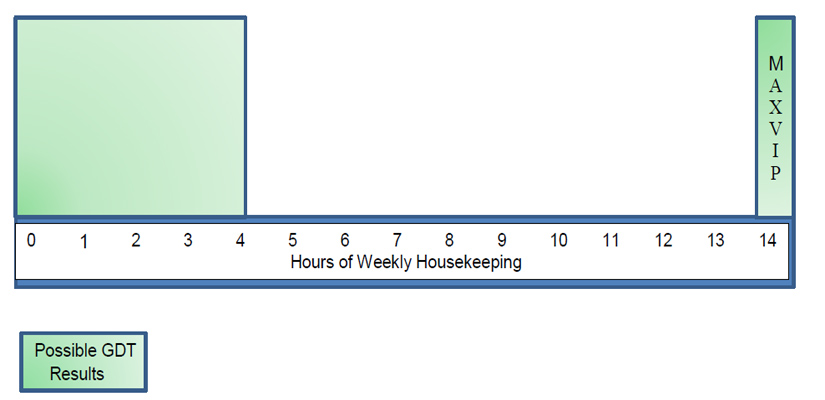

VAC staff who were interviewed noted the GDT adds much-needed consistency to the determination of Program benefits. It also provides assurance that Veterans across the country are receiving equitable treatment. Staff also noted, however, that although the tool adds consistency, it does restrict flexibility in certain instances. For example, it was highlighted during interviews that the GDT scoring scale will not produce a result whereby a recipient can receive between 4 and 14 hours of housekeeping per week. See Figure 3.

Figure 3: Housekeeping Hours Received when GDT is Applied

Figure 3: Housekeeping Hours Received when GDT is Applied

| Possible GDT Results | GDT Gap |

|---|---|

| 0-4 and 14 | 4-13 |

Slight differences in responses provided on the GDT can cause large differences in the number of housekeeping hours received. See Appendix B - Level of Needs Table for greater detail.

The evaluation team studied this issue further by running scenarios in a GDT test environment. Through these scenarios, the evaluation team pinpointed an issue with the GDT’s level of need scoring for housekeeping. For example, if the Veteran has a level of need score of 5.5 to 6 they will receive 4 hours of housekeeping every week. If the Veteran has a level of need score greater than 6, they will receive 14 hours of housekeeping weekly. See Table 6.

Table 6: Comparison of GDT scores for two Veterans who live in medium sized houses without family support, one needing significant assistance with cleaning and one needing regular assistance with cleaning.

| Veteran # 1 | Level of Needs Score |

|---|---|

| Level of Need: | |

| Meals - Significant | 2 |

| Errands - Significant | 1 |

| Cleaning - Significant | 2 |

| Laundry Regular | 1 |

| House Size - Medium | .5 |

| Total level of needs score | 6.5 |

| Total Hours VIP Housekeeping | 14/week |

| Total Grant Paid | $18,031 |

| Veteran # 2 | Level of Needs Score |

|---|---|

| Level of Need: | |

| Meals - Significant | 2 |

| Errands - Significant | 1 |

| Cleaning - Regular | 1 |

| Laundry Regular | 1 |

| House Size - Medium | .5 |

| Total level of needs score | 5.5 |

| Total Hours VIP Housekeeping | 4/week |

| Total Grant Paid | $5,137 |

The two examples above, along with Figure 3, highlight an issue with how the GDT determines housekeeping hours; the tool will not produce results in the 4-14 hour range. A review of GDT assessments completed during the 2015 calendar year showed that this could affect approximately 1,600 recipients may be affected (applicants could receive too much support or too little).

The administration of the GDT is completed through a telephone interview. VAC and Processor staff noted that this method does not allow for a view into the home. For example, over the telephone, a Veteran with dementia may indicate their health as being good, but not mention that they recently fell and have a broken bone or are constantly leaving the stove on.

Research indicates that provincial health authorities also follow the telephone model of assessment. However, in the provincial model, staff who provide services are employed by the province and are in direct contact with the recipient. This allows for observation of the situation and modifications to home care as required.

4.4 Additional Observations

As per the 2012 VIP Renewed Terms and Conditions, follow-up activities are conducted annually to ensure continuing entitlement to Program services and compliance with the terms of the benefit arrangement.Footnote 48 Early in 2015, outside the evaluation period, a new follow-up process was implemented that reduces the frequency of direct contact with benefit recipients from once per year to once every three years. This could result in the automatic renewal of benefit arrangements for up to three years without direct contact with the recipient.

Reducing recipient contact increases the risk that recipients’ needs may not be identified. In addition, reducing contact increases the risk of overpayments to recipients, especially in cases where recipients change their place of residence.

As this change occurred outside the period of the evaluation, the evaluation team did not investigate further beyond determining that the Department is aware of the issue and is actively monitoring it. Program management has committed to reviewing the results of follow-up phone calls conducted in the first year to determine if more measures should be put in place to ensure the Department is notified quickly should a recipient’s needs change. Further, Program management has requested that the Department’s processing of notifications received for program recipient address changes be completed sooner in order to minimize delays in benefit increases and reduce the occurrence of overpayments.