3.1 Effectiveness

The evaluation assessed the effectiveness of the OVO based on its own performance indicators such as responding to and resolving Veterans complaints, providing fair and respectful treatment, and engaging with Veterans. It also examined the impact of its key recommendations.

3.1.1 Resolving Veterans/Clients Complaints

Finding 1: Overall, the OVO has been successful in addressing most inquiries and complaints within its mandate. Its performance in addressing/closing complaints within sixty days significantly improved over the last five years. The limits of authority within which the OVO can address Veterans’ issues is the key barrier to its overall effectiveness.

The degree to which the OVO was effective in resolving Veterans’ complaints is noted below against each of the OVO’s key roles (addressing individual inquiries and complaints; conducting systemic investigations; providing advice to the Minister and Parliamentarians).

Individual Inquiries and Complaints

The review of documents confirmed that Veteran/client issues brought to the OVO’s attention over the period under review were varied. They included disability awards/pensions, medical treatment allowances/rehabilitation and vocational assistance, VRAB decisions, Bureau of Pension Advocates (BPA) service delivery, and the complexity and turnaround time related to VAC’s benefits and application processes. Of these, disability issues and VAC turnaround time for a decision on a disability benefit application accounted for the majority of cases. For example, the OVO 2018/2019 Annual Report noted that 50 percent of enquiries/complaints concerned disability issues, with 79 percent associated with turnaround time. As well, OVO respondents noted that virtually all unresolved files over the last 5 years were due to disability award turnaround time (which the OVO does not have the authority to address unless there are compelling circumstances). The OVO noted that in the last 6 months (2019-2020), of the 300 valid complaints, 270 (90%) were about turnaround time.

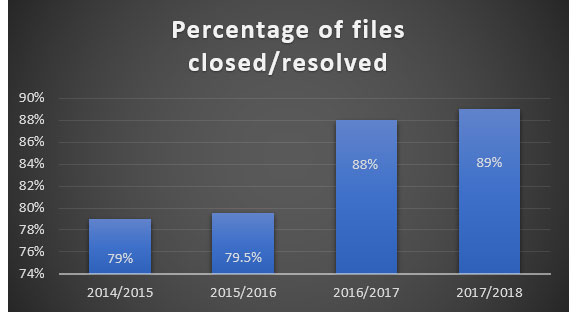

A review of Departmental Performance Reports, which included OVO performance indicators, showed that the percent of issues raised by Veterans and other individuals that were being addressed by the OVO was an average of 83.5 percent between FY 2014/2015 and 2017/2018, 3.5 percent above the 80 percent performance target. Figure 1 below provides a breakdown of files openedFootnote 8 and addressed/closed by fiscal year during that period. This includes a significant number of referrals to the authorities best positioned to handle the issues raised by Veterans/clients. Figure 1 also shows that the OVO made significant progress in FY 2016/17 and 2017/2018 in resolving cases, with an increase of 10 percent between 2014/2015 and 2017/2018. OVO reports and internal respondents noted that changes made to the case management system have improved how the OVO tracks files and analyzes data. Improvements in efficiency are discussed in more details in Section 3.3.

Figure 1: Percentage of Files Closed/Resolved by the OVO

Figure 1: Percentage of Files Closed/Resolved by the OVO

| 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of files closed/resolved | 79% | 79.5% | 88% | 89% |

Source: Ombudsman File Tracking System (OFTS)

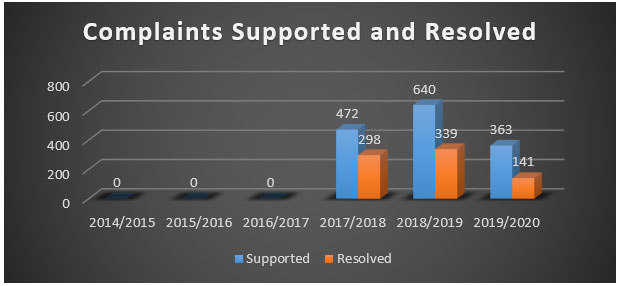

As Figure 2 shows, the number of complaints handled each year varies. This is due to a number of issues and changes that occur over time (e.g., clients getting results through the VAC appeal process; tracking methods for dating unresolved files, etc.) Available data showed that for FY 2017/2018,Footnote 9 the OVO assessed 472 complaints within its jurisdiction to have an unfairness component, with 298 (63%) resolved in favour of the Veteran/client. In 2018/2019, it investigated 640 with an unfairness component and 339 (53%) were resolved in favour of the complainant. In FY 2019/2020 (incomplete), the OVO investigated 504 complaints, with 363 having an unfairness element and 141 (39%) were resolved.

Overall, the unresolved complaints were related to the turnaround time for the adjudication of Disability Benefits (outside of OVO mandate). VAC is dealing with a substantive backlog in this area.

Figure 2: Number of Complaints Supported and Resolved by the OVO

Figure 2: Number of Complaints Supported and Resolved by the OVO

| 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supported | 0 | 0 | 0 | 472 | 640 | 363 |

| Resolved | 0 | 0 | 0 | 298 | 339 | 141 |

Source: OVO OFTS

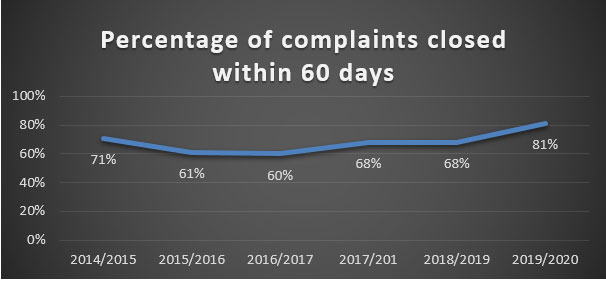

As to the number of complaints addressed within the 60 working day service standard (performance target: 75%), the data showed a lot of variation during the period under review, with an overall improvement of 10 percent between 2014/2015 and 2019/2020. As Figure 3 shows, there was an overall increase from 71 percent to 81 percent (exceeding the target in 2019-20)Footnote 10. However, performance decreased from 2015/2016 to 2018/2019, with variations from 60 to 68 percent, significantly lower than expectations.

Figure 3: Percentage of Complaints Closed within 60 Days

Figure 3: Percentage of Complaints Closed within 60 Days

| 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complaints closed | 71% | 61% | 60% | 68% | 68% | 81% |

Source: OVO OFTS

The Veterans interviewed indicated that the OVO is partially helpful in addressing their complaints due to the limited mandate (some believing that the OVO is effective and others not). The sample was too small to draw conclusions on the different perspectives expressed but those who were in contact with the OVO through consultative or Parliamentary Committees, for example, had a more positive opinion on the effectiveness of the OVO. Several Veterans noted that the OVO was their last resort after a long and frustrating appeal process.

Case studies confirmed the findings noted above and showed that individual complaints have become increasingly complex in recent years with the review process within the OVO requiring lengthy back and forth with VAC to obtain and analyse information.

Other than the limited mandate of the OVO in terms of what it can address to help Veterans/clients, the evaluation did not find other significant barriers that affected its effectiveness. Research reports noted a variety of barriers related to VAC programs and services, leading to recommendations from the OVO to VAC, but these were not barriers that specifically prevented the OVO from achieving its outcomes.

Finding 2: While the OVO treats Veterans/clients with respect in handling their complaints, the OVO could be timelier and more transparent in its communication with Veterans.

When considering how Veterans are treated by the OVO, information was available from client feedback gathered by the OVO and from the interviews conducted with Veterans and VAC. Veterans, VAC and external stakeholders interviewed all agreed that the OVO treats Veterans/clients respectfully and fairly. This was consistent with client feedback surveys conducted by the OVO in 2018-19 and 2019-20, which showed that the vast majority were satisfied with the treatment they received from the OVO. According to OVO client feedback data (summary of data from 2018-19 and first half of 2019-20):

Figure 4: Level of Satisfaction with Treatment Received from the OVO

- 78% agreed they were treated with respect at all times during the process

- 73% agreed they had sufficient opportunity to explain their complaint

However, a few of the Veterans interviewed and client feedback collected by the OVO indicated that the Office could be more transparent and timelier in responding to Veterans/clients’ enquiries regarding their complaint. For instance, surveys conducted by the OVO with clients from 2018-19 and first half of 2019-20 indicated that only 58 percent felt they were provided with clear information of the steps following their call, 54 percent felt that the OVO response to their complaint was clear, and only 41 percent agreed that they received a response when indicated. Some Veterans interviewed for this evaluation also mentioned that they would prefer to receive a letter from the OVO summarizing their case.

The Veterans who raised concerns when interviewed noted that despite repeated calls or letters to the OVO, months could go by before they got an answer to their enquiry regarding their claim. The key cause of these delays was thought to be a lack of staff resources to handle the caseloads. Nonetheless, for these Veterans, these delays added to the frustration they felt as a result of the lengthy VAC appeal process. According to OVO respondents, those delays were due in large part to a backlog caused by some inefficiencies, staff turnover and difficulty in recruiting staff in Charlottetown. The documentation reviewed and interviews showed that the OVO has taken steps to reduce this backlog (see Section 3.3 on Efficiency).

Systemic Investigations

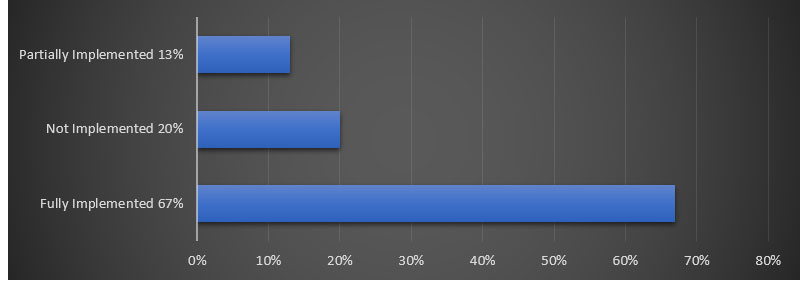

Finding 3: Most of the OVO’s recommendations to VAC made through systemic investigations have been implemented or partially implemented.

The review of documents indicates that the OVO has published from two to four studies/systemic investigations annually. Topics have included, for example, health care/ impairment allowances, Veterans’ rights to know reasons for decisions, fair compensation for pain and suffering, fair treatment for Veterans and their families in transition, disability benefits, fair adjudication, and continuum of care.

VAC and OVO key informants noted that the OVO has the freedom to determine which topics it investigated. They noted that topics for investigations came from various sources but that they are mostly based on complaints and/or Veterans’ input. Several key internal stakeholders noted that the OVO has taken a strategic approach to selecting review topics.

The documents showed that the OVO has a good track record in terms of the implementation of recommendations it made to VAC. Reports for 2014/2015 and 2015/2016, before the OVO started to produce report cards on the implementation of its recommendations, indicated that the percentage of recommendations accepted by the department was 91 and 93 percent respectively, much higher than its performance target of 80 percent.

Figure 5 below shows that over three years, between 2016/2017 and 2018/2019, VAC implemented or partially implemented most of the recommendations made by the OVO in systemic investigations, with 67 percent fully implemented and 13 percent partially implemented, for a total of 80 percent (note that there is often a time lag in implementation as it takes time to secure funding, adjust authorities and processes, etc.)

Figure 5: Percentage of OVO Recommendations Implemented 2016-17 to 2018-19

Figure 5: Percentage of OVO Recommendations Implemented 2016-17 to 2018-19

| Fully Implemented | Not Implemented | Partially Implemented | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of OVO Recommendations Implemented | 67% | 20% | 13% |

Source: OVO Report Card 2019

Table 5 provides a more detailed overview of the percentage of recommendations fully (FI), partially (PI) or not implemented (NI) by area of recommendation between FY 2016/2017 and 2018/2019, based on the OVO report cards. As the numbers show, VAC has implemented in large part recommendations in areas such as life skills and preparedness, financial security and service delivery (Veteran’s Experience). The OVO has been less successful in seeing VAC implement recommendations in the health care and support area.

| Area of Recommendation | # of Rec. | FI | PI | NI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Care and Support | 10 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Veterans Experience with VAC | 25 | 14 | 7 | 4 |

| Financially Secure | 19 | 18 | 1 | |

| Life Skills and Preparedness | 4 | 4 | ||

| Purpose (e.g., employment or other meaningful purpose) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Social Integration | 4 | 4 | ||

| Total | 63 | 42 | 8 | 13 |

Source: OVO Report Card 2019

The documents reviewed also showed that the most recurring complaint received by the OVO was VAC’s turnaround time to process claims. The OVO systemic investigation of VAC’s turnaround time published in 2018 (see Case Study 3, Annex 3), found that while VAC met the 16-week service standard for applications from World War II or Korean War service Veterans, the majority of all other disability benefits first decision took longer - sometimes much longer, based on its review of over 1,000 files. The investigation found that this was particularly the case for Francophone and women applicants, and there was a lack of prioritization based on health and financial needs. The OVO also found that Veterans and families experienced a lack of transparency and communication throughout the process in terms of how turnaround times are reported, the status of Veterans applications, or the reasons for delays. It made seven recommendations to VAC. At the time of report writing, the department had implemented three of the seven of the OVO’s recommendations.

The fact that VAC had not implemented all recommendations is due to several factors. Most key informants noted that some recommendations do take more time to be implemented due to the considerable amounts of money involved, and the complexity of implementing some recommendations.

Appearing Before Parliamentary Committees

Another opportunity for the OVO to weigh in on Veterans concerns is when the Ombudsman is asked to appear before parliamentary committees. Annual reports indicate that the Ombudsman, supported by the Deputy Ombudsman, often offers testimony on issues of concern to Veterans and their families, appearing 2 to 3 times, on average, each year. These appearances include before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs (ACVA); Senate Sub Committee on Veterans Affairs, and, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance (FINA). The testimony serves the purpose of informing Committees on issues they are exploring on behalf of the government.

3.1.2 Awareness, Outreach and Engagement

Finding 4: Many Veterans/clients are not aware of the OVO or familiar with its role. The OVO’s outreach has increased over time, particularly through social media, but more could be done to improve Veterans’ awareness of the OVO and its mandate.

Awareness of the OVO

A national survey that VAC conducted in 2017 revealed that most Veterans and other clients of VAC were not very aware of the OVO, with only 54 percent of survey respondents indicating they ‘have heard’ of the OVO, broken down by: Veterans (63%); RCMP (59%); Survivors (37%). As well, 93 percent responded that they were ‘not very familiar’ with the OVO, having only superficial knowledge its role. Based on the OVO database (client feedback), Veterans are more likely to hear about the OVO from the CAF, VAC or the Internet than from Veterans’ organizations, friends/family or social media.

This lack of awareness of the existence and role/mandate of the OVO was confirmed by key informants. Most interviewees thought that the majority of Veterans were not aware or fully aware of what the OVO can/cannot do. Most Veterans interviewed thought that many Veterans do not know about the OVO; as well, some of them noted Veterans may not be accessing the OVO due to a lack of trust in its effectiveness or simply from being exhausted or discouraged after having gone through a lengthy process with VAC.

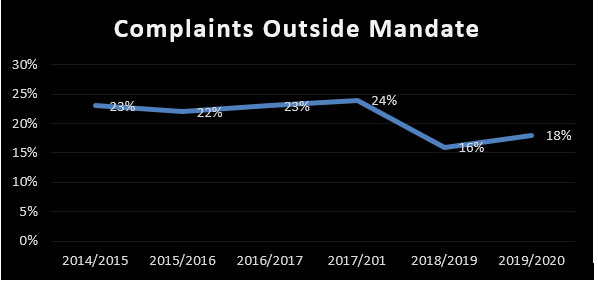

A potential indicator of the level of awareness of Veterans with the OVO’s role is the percentage of complaints received that are outside the mandate of the OVO. The statistics compiled by the OVO show that an average of 21 percent of complaints received have been outside of mandate over the last 6 years. However, this level has decreased recently. As Figure 6 shows, there was a 5 percent decline in complaints outside of the OVO’s mandate between 2014/2015 and 2019/2020, from 23 percent to 18 percent.

Figure 6: Percentage of Complaints Outside the OVO’s Mandate

Figure 6: Percentage of Complaints Outside the OVO’s Mandate

| 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complaints Outside Mandate | 23% | 22% | 23% | 24% | 16% | 18% |

Source: OFTS

Overall, most interviewees thought that the OVO should do more outreach to inform Veterans and make the existence and role of the OVO more explicit. It was suggested that this be done through the OVO and/or VAC websites and by participating in events organized by Veterans organizations. One suggestion was to include summary information about the OVO and its phone number / website on all VAC correspondence with Veterans.

Outreach and Engagement

With regards to outreach and engagement, OVO documents show a three-fold increase in the number of calls made to the OVO from 2014/2015 to 2017/2018 (the number of emails remained constant with an annual average of 1,336). During the same period, the number of complaints made online through the complaint form increased from 146 to 655 (note increases are usually seen after VAC program/benefit changes).

While the OVO maintained its presence via the traditional media (interviews, press releases, etc.), and the number of town hall and stakeholder meetings (e.g. with official Veterans organizations) remained relatively constant over the years, there was a significant increase in the use of social media (e.g. Twitter, Facebook and Blog posts, followers, etc.) to reach and communicate with Veterans/clients. A review of annual reports shows that Tweets increased from 568 to 2,600 and Facebook followers increased 2,143 in 2014/2015 to 5,100 in 2017/2018. In the last two years, the OVO conducted two live Facebook events and reported that one of these events on Pension for Life reached over 19,000 people. At the same time, the number of visitors to the OVO website was approximately 35,500 on average in the last two years.

Veterans expressed mixed views on whether they are engaged appropriately. Most of those interviewed mentioned that they follow the OVO on social media and read its reports. Some argued that traditional means of reaching out to Veterans such as town halls were no longer as effective since Veterans are spread out across the country and often live away from major centres, while others noted that the town halls had value and were well attended. A few noted that the OVO could have a presence at Veterans’ rallies, which are well attended, to enhance outreach; and, others noted the value of social media outreach.

A few Veterans also questioned the relevance of Veteran service organizations to represent their interests (e.g., in stakeholder meetings) and felt that some organizations may be in conflict of interest as VAC service providers. As such, these Veterans thought that the OVO should engage consult/engage directly with the Veterans and their families (not via Veterans organizations). While it was recognized that there are many Veterans’ groups all with different objectives, a few Veterans noted that the ‘modern’ groups need to be included in consultations as they better represent the interests of the wounded.

What is clear from the data is that Veterans are increasingly using social media to interact with and get information from the OVO. The sample of interviewees was too small to draw conclusions on the continued effectiveness or relevance of town halls and stakeholder meetings but it may be something that the OVO wishes to explore in more depth in the future.

3.1.3 Impact of the OVO

Finding 5: OVO systemic investigations and advice to Parliamentarians have resulted in positive impacts for a large number of Veterans. However, few individual cases addressed by the OVO have led to a change in outcomes for Veterans. In spite of this, the impact of these changes for the individuals concerned can be significant.

Individual Complaint Investigations

Several OVO respondents noted that the percent of individual complaints leading to a reversal of a decision is in fact quite low. Data compiled by the OVO on individual reversals in VAC’s decisions from individual complaints show that it is indeed small. For instance, data for 2018/2019 (see chart) shows that 4 percent of OVO individual complaint investigations resulted in a changed outcome (based on total complaints investigated).

Diagram 4: Complaints F/Y 2018-19

This diagram details the impact of the OVO on individual cases. The case flow from initial client contact with the OVO until resolution is depicted in a Sankey flow diagram.

The diagram indicates that the OVO was contacted 2,001 times in 2018-19, broken down into 1,681 complaints and 320 enquiries. Of the 1,681 complaints, 1,570 were within the OVO mandate while 111 fell outside the mandate. In all, complaints comprised 88% of all OVO intake, with 78% falling within the OVO’s mandate.

In total, 1,153 complaints were investigated by the OVO, while 417 complaints were closed without an investigation (98 were resolved at intake, with 319 redirected back to VAC). Complaint investigations occurred in 58% of the cases where a Veteran contacted the OVO.

Of the 1,153 complaints investigated by the OVO:

- 628 were deemed to be valid (31% of the original OVO intake);

- 405 were deemed to be invalid; and

- 120 are still under review.

The diagram breaks valid complaints into three categories: Service Delivery, Disability Benefits, and VRAB.

| Complaint Area | # Complaints | Resolved (53% of valid complaints) | Unresolved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Service Delivery | 117 | 116 | 1 |

| Disability Benefits | 510 | 213 | 293 |

| VRAB | 1 | 1 | 0 |

All 293 unresolved disability complaints and 202 resolved disability complaints related to turnaround times. The diagram also indicates that 26 cases were resolved without OVO help, while 4 cases remain unresolved for other reasons.

Of the resolved complaints that did not relate to turnaround times, the diagram indicates:

- 41 were related to decisions

- 39 were related to process

- 19 were related to treatment

- 4 were treated fairly

The diagram indicates the following results from the resolved complaints.

| Resolved Complaint Type | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Changed Decision | Facilitated Access | Provided Information | |

| Decision | 29 | 9 | 3 |

| Process | 3 | 31 | 5 |

| Treatment | 0 | 14 | 5 |

| Total | 32 | 54 | 13 |

The diagram concludes that 45 Veteran outcomes were changed as a result of either a changed decision (32) or facilitated access (13). An addition 54 Veterans experienced improved engagement through facilitated access (41) or the information they were provided (13). In total, 99 Veterans experienced a change in outcome or improved engagement.

Of the original 2,001 contacts made with the OVO, approximately 2% resulted in a changed outcome for the Veteran. Of the 628 valid complaints, 7% resulted in a changed outcome for the Veteran.

However, the impact of the OVO can be significant for those individual complaints that they are able to address. For example, in one 2019 report, the OVO remarked that providing a $150 railing to allow a Veteran to safely move from one part of his house to another may not seem a big deal but it is for the individual. Other individual outcomes found in various reports included:

- $324,000 + lifetime financial support provided to a dependent adult child;

- Life changing dental care;

- Dying Veteran receives end of life support;

- Funding restored to 90+ year old Veteran; and

- 97-year-old Veteran provided with housekeeping and family support that kept him in his home.

The case studies (see Annex 3) illustrated the type of outcomes that can make significant differences in a Veteran’s life. In one case, $136,000+ was awarded to a Veteran’s surviving spouse as a result of the reversal of VAC’s decision. The other individual case study showed that the award of a Career Impact Allowance (CIA) as a result of injuries leading to chronic pain can make a real difference for a Veteran’s quality of life and financial security.

The Veterans interviewed also considered that providing support to individuals was a key role for the OVO.

Systemic Investigations

The evaluation found that systemic investigations can have far-reaching impacts in terms of the amount of money going into Veterans pockets and in terms of the number of Veterans benefiting from suggested changes. The documentation reviewed provided compelling evidence of this impact and all key informants shared this view.

The documentation showed that, both in Budget 2016 and Budget 2017, the federal government directly addressed several of the OVO’s recommendations (although not every aspect of them was addressed), providing nearly $10 billion to implement OVO and other recommendations, leading to increases in Disability Awards, Earnings Loss Benefits, Caregiver Compensation, and Education and Training Benefits, among others.Footnote 11

The OVO reports noted that it included increasing the Disability Award to a maximum of $360,000, and increasing the Earnings Loss Benefit to 90 percent of gross pre-release military salary. The changes also included eliminating the time-limit for spouses and survivors to access vocational rehabilitation, expanding access to the Military Family Resource Centres, improving outreach to families, closing the seam for members transitioning to civilian life, and providing additional support directly to the caregivers of ill and injured Veterans through the new Caregiver Recognition Benefit. The Government of Canada characterized this new benefit as a substantive step forward in recognizing that family members who act as caregivers need benefits in their own right given the significant role many play in supporting Veterans.

In 2017/2018, the OVO discovered a miscalculation in the grade levels related to years served for the Career Impact Allowance. The OVO alerted the Department of the error, which was immediately resolved. Correcting this mistake raised the grade level of 134 Veterans, who received an additional $600 monthly.

The list below provides other examples of the key systemic contributions made by the OVO in recent years to improve the life of Veterans:

- Veterans Homelessness is recognized as an issue;

- $14 Million in retroactive payments for 600 Veterans;

- $1 Million in annual payments for 133 Veterans;

- $10 Million in annual payment for 1,500 Veterans; and

- $150 Million accounting error affects 100,000+ Veterans, survivors and estates.Footnote 12

Influence Decision Making

Internal key informants noted that OVO advice to Parliamentary Committees was very impactful, pointing out that OVO recommendations have been cited in federal government budgets, Ministerial mandate letters and Parliamentary reports. For example, OVO annual reports note that:

- In September 2014, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance (FINA) emphasized the importance of funding the changes recommended by the OVO in ‘The New Veterans Charter: Moving Forward’;

- The VAC Minister’s mandate letter (2015) reflected several recommendations previously put forward by the OVO, namely reducing complexity and overhauling service delivery, increasing the Earnings Loss Benefit to 90 percent of pre-release salary, expanding access to the Permanent Impairment Allowance (now called the Career Impact Allowance), increasing the value of the Disability Award, and ending the time limit for surviving spouses to apply for vocational rehabilitation and assistance services; and,

- The FINA Study of Bill C-44, ‘An Act to Implement Certain Provisions of the Budget’ was tabled in Parliament on March 22, 2017. The Veterans Ombudsman’s May 19, 2017, brief noted that he was pleased that the Government had taken his recommendations and those of many Veterans’ organizations seriously and in Bill C-44 was moving forward on several of them.

In spite of all the changes noted above, in its 2016-2017 Annual Report, the OVO noted that there still exists unfairness in many areas, including service delivery. It states that “putting in place a simplified and efficient Veteran-centric service-delivery approach will require continued collaboration to ensure that even the most complex cases get the right level of support and that all Veterans are treated fairly.” Based on the interviews conducted as part of this evaluation, this is still an unresolved and central issue from the perspective of the OVO.

3.2 Efficiency

The evaluation assessed whether the OVO performance strategy is adequate, its governance structure appropriate and efficient, as well as if activities were delivered in an efficient and economical manner. The evaluation also examined whether alternative structures or delivery options would enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the OVO.

3.2.1 Performance Strategy

Finding 6: The OVO has a robust and updated performance measurement strategy supported by timely and reliable data. Performance indicators used by the OVO are similar to those of other Ombuds offices. Performance information is used by the department and taken seriously, but needs to be clearer to Veterans on what can and cannot be implemented and why.

The OVO reports on its performance both through its annual reports and through the VAC Departmental Results Framework (DRF). It has recently updated its performance measurement framework which included updating the DRF and the OVO Performance Information Profile (PIP), along with a new logic model (see Annex 1). This new performance framework better reflects the intended outcomes of the OVO, has clearer outcome statements, and the new logic model has clear causal links between outcomes and the ultimate outcome. Most of the indicators in the new PIP can be measured accurately and in a timely manner by the OVO through existing systems, though some systems had to be adjusted to collect new data (currently underway). The PIP includes both effectiveness and efficiency indicators.

The OVO’s data system (OFTS) provides comprehensive performance data on complaints (since 2007) and the public ‘Report Card’ assesses the implementation of systemic review recommendations (since 2009). Over the last year, the OVO has also been collecting data on client service experiences on a quarterly basis and has client awareness data from the VAC National Survey conducted every three years.

Internal key informants indicated that the OVO’s performance information is used by the department, reported publicly, and taken seriously. However, some internal and external informants noted that OVO’s public reports and recommendations need to be clearer on what issues can and cannot be addressed by VAC, and why. Informants also said that OVO management could use its data more strategically (and the OVO is now creating dashboards) and most believe the OVO could promote its role and recommendations more with the public (e.g., via website, by including information on VAC correspondence to Veterans, etc.).

While annual public reporting on performance is common and seen as important for Ombuds institutions, so also is the recognition that measuring success is challenging. Most offices examined in the comparative assessment reported on their performance in annual reports in the same way as the OVO, including:

- Number and type of complaints (and trends over time);

- How complaints are provided (e.g., phone, online);

- Timeliness in addressing complaints;

- Number and type of investigations and % of recommendations accepted /acted upon;

- Outreach and communications statistics; and

- Expenditures against budget.

Other Ombuds offices suggested that success could be also be measured through:

- Stakeholder surveys on level of awareness of office, as well as views on effectiveness, trust, credibility and impartiality of the office (noting that assessing ‘fairness’ is not the same as ‘client satisfaction’) [N.B. the OVO has recently been soliciting client feedback];

- Third party endorsements of recommendations [N.B. the OVO does this sometimes by issuing recommendations jointly with Veterans groups such as the RCL];

- The success of advice/ recommendations to influence policy change; and

- The use of the office by others (e.g., citations, consultations).

3.2.2 Governance Structure

Finding 7: The OVO has a clear and stable governance structure, with clearly defined responsibilities with respect to VAC and the Advisory Council.

Documentation indicated a well-defined governance structure in the OVO (as detailed in Section 1.3), with clearly laid out responsibilities with respect to the department and the VOAC (e.g., updated MOU and SLAs with VAC, Terms of Reference for VOAC). The organizational structure of the OVO has remained fairly constant over time and no issues were noted in terms of its effectiveness.

While the operational environment of the OVO is impacted by changes in VAC programs and by leadership changes in the Ombudsman position (a new Ombudsman was appointed in November 2018), the program areas in the OVO are clear, stable and well-defined. As well, financial allocations have remained relatively stable over time. Integrated business plans have been completed and a strategic plan is now under development with a new Ombudsman.

The OVO has established a new structure for the frontline services to enhance efficiencies and, with this, has plans to also establish a Quality Assurance Manager and Team leads (French & English) to better address workplace issues and improve morale.

While the governance structure is viewed by all internal informants as appropriate, there are some concerns with succession at the management level in the OVO (as there will be a number of managers in key positions retiring around the same time).

3.2.3 Efficiency and Economy of Delivery

Finding 8: Organizational design changes have been made in the OVO to increase frontline efficiency. Workflows and micro-investigations are also being implemented to increase efficiencies. Further plans are being made to enhance training and integrate online tools into the management of complaints. Timeliness to respond to complaints has improved over time and the backlog is being reduced. Further efficiencies may be possible with staff specialization and greater familiarization with Veterans’ issues.

Process Efficiencies

The OVO was been working to enhance its efficiencies in a number of ways:

- In 2016/2017, following an Organizational Design Study, the Office launched ‘Operation Revitalization’ to streamline front line processes (e.g., separation of intake and investigative officers/roles).

- In 2017/2018, the OVO updated its File Tracking System to better manage workloads and provide further information on trends. The Office also implemented an online complaint application, and has future plans to integrate online complaint data with the File Tracking System. The Office also launched a Lean Business Process Improvement initiative.

- In 2019/2020, workflows were developed to better manage systemic report projects. The Office also initiated the process of doing ‘micro’-investigations for ‘simpler’ systemic issues that would be produced more quickly than the more detailed systemic investigations.

- There are further plans to add front line resources in Ottawa to extend service hours and expand the provision of French services, as well there are plans to provide comprehensive front line training to further expedite ‘easy to fix’ complaints.

Key internal and external informants suggested that, to further improve efficiencies, there could be more staff specialists on the front line (e.g., marijuana, mental health issues), and the frontline could benefit from having more experience overall with Veterans’ issues. Veterans/stakeholders interviewed emphasized the importance of having OVO staff who understand and have experience with Veteran’s issues.

Timeliness

While the OVO noted there was a noted lack of capacity/staff to address all complaints quickly, which has caused a backlog; timeliness and the backlog have improved over time:

- In terms of timeliness, the percentage of cases closed within 60 days has increased from 61 percent in 2015-16 to 81 percent at this point in 2019/2020.

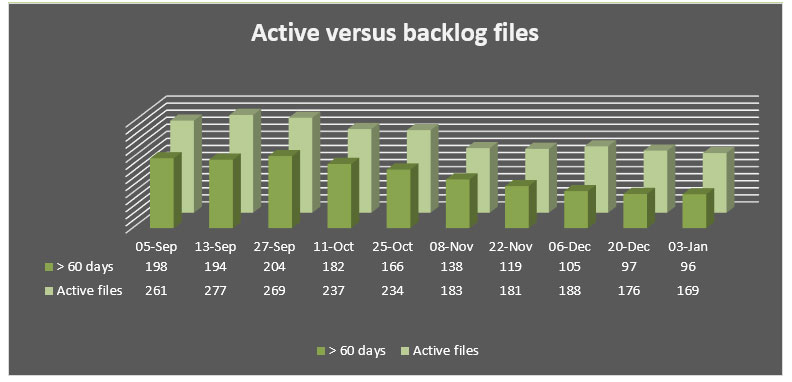

- In terms of the backlog, the number of files that have been active for more than 60 days has been reduced by 52 percent between September 2019 and January 2020, as shown in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7: Front Line Workload - Active Versus Backlog Files

Figure 7: Front Line Workload - Active Versus Backlog Files

| 05-Sep | 13-Sep | 27-Sep | 11-Oct | 25-Oct | 08-Nov | 22-Nov | 06-Dec | 20-Dec | 03-Jan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 60 days | 198 | 194 | 204 | 182 | 166 | 138 | 119 | 105 | 97 | 96 |

| Active files | 261 | 277 | 269 | 237 | 234 | 183 | 181 | 188 | 176 | 169 |

Source: OVO OFTS

The case studies provided two examples of complaints that took more than the standard 60 days to close (one took up to 2 years). The factors noted in these cases that caused time delays included: the complexity of the cases (e.g., initial decline of application by VAC requiring more information from the OVO, the requirement for legal interpretation), the time required to get necessary information from VAC, and delays in receiving final responses from VAC.

Expenditures

The OVO consistently underspent against plans by a four-year average of 15 percent; and, consistently underspend against authorities by a four-year average of 11 percent. However, the variance in spending against plans and authorities has been reduced (spending closer to plans) over time (e.g., only 5-9 percent underspending in 2017/2018; and on track to reduce percent in 2019/2020).

While it is problematic to make direct comparisons, when attempting to compare efficiency between the OVO and some other federal Ombuds offices, the comparative assessment showed that the ratio of workload (number of cases) compared to budget and staff between offices is within same parameters.

Finding 9: The key barriers to efficiency within the OVO include staff turnover and recruitment challenges, and reliance on corporate support and responses from VAC. Frontline efficiencies may be enhanced with OVO abilities to mediate complaints. From the Veteran’s perspective, there is inefficiency in the Government’s multi-layered review/appeal ‘ecosystem’ which involves multiple parties.

OVO key informants noted a few specific efficiency barriers:

- The OVO is a small organization with fewer opportunities for advancement and different classification levels than VAC, which can cause them to lose staff to the department.

- The frontline officers face stressful situations, people and issues on a regular basis, and they operate in an open office (based on government standards) which can challenge their ability to operate efficiently and can increase turnover.

- The OVO’s location in Charlottetown can create staff recruitment challenges, particularly for bilingual resources.

- The OVO provides 10 FTEs to VAC for response services and relies on VAC for corporate support. This hampers the OVO’s ability to be quick and nimble both in terms of providing responses and updating processes (e.g., IT system priority and updates).

Overall, as noted previously, there is redundancy in dealing with Veterans’ complaints at multiple levels by multiple agencies (VAC, VRAB, OVO) that does not lend itself to efficiency in dealing with Veterans’ issues.

Some key informants in the OVO, as well as a few Veterans, suggested that OVO-driven mediation, negotiation and/or arbitration (~alternative dispute resolution or ADR) could bring faster results that provide appropriate legal and ethical relief to the Veteran and prevent similar conflicts from occurring in the future. For example, the federal Procurement Ombudsman is using ADR as a “way to minimize the pain of nasty disputes over the procurement process”.Footnote 13 Also, in 2018, the Government of Australia conducted a study on how veterans and their families are assisted to access entitlements and services. The study found that ADR is an effective process to resolve matters without a Board hearing and that 65.1% of cases were decided without a hearing in 2017-18.Footnote 14 However, this option for the OVO to include ADR requires further study as it was out of the scope of this evaluation.

3.2.4 Alternative Governance Structure and Delivery Options

Finding 10: An alternative structure with one integrated federal ombudsman office, reporting to Parliament for independence, could lead to efficiencies for the Government of Canada. However, further study into alternative structures is warranted before any conclusive finding can be made on the most efficient and effective option for providing federal Ombuds services.

The key suggestion from most other Ombudsmen to increase efficiency, as noted in the comparative assessment, was to bundle all the federal ombudsman offices together into one national Ombuds office that reports to Parliament, with different branches for specific topic areas. This would allow for efficiencies to be gained in terms of staffing (consolidated intake) and corporate services. It would also provide a more independent, simplified and accessible “one-window” for clients. The Venice Principles do not favour one structure or model, noting that the ‘choice of a single or plural Ombudsman model depends on the State organization, its particularities and needs. The Ombudsman Institution may be organized at different levels and with different competences.’Footnote 15

A number of OVO key informants and other federal Ombudsman offices also supported the idea of one federal Ombuds office; however, there were a range of other views also expressed including: having the OVO report to Parliament (as per the Venice Principles), and, merging the OVO with the DND/CAF Ombuds office.

3.3 Relevance

The evaluation assessed the relevance of the OVO mandate in light of the changing needs and expectations of Veterans/clients and the changing context in which it operates, as well as whether the OVO has an appropriate level of impendence.

3.3.1 Expectations of Veterans/Clients

Finding 11: Veterans expect an independent body to assist them when they believe their rights have not been respected. They expect the OVO to have the authority to investigate any complaint or issue related to Veterans services. However, the OVO’s mandate limits its ability to address key areas of concern, and the review/appeal system is complex and burdensome for Veterans. Despite its narrow mandate, the OVO remains relevant both to address individual complaints and particularly to address systemic issues affecting Veterans.

Interviews with Veterans indicate they expect the OVO to assist when their rights have not been respected, or have been treated unfairly and believe the OVO should have the authority to investigate any complaint or issue regarding the implementation of VAC policies. While Veterans noted that there are other organizations that offer support and help as service providers (e.g. the RCL helps with benefit applications), they believe that the OVO’s role is to intervene when there is any unfair treatment by VAC. Individual case studies also showed that Veterans expect the OVO to help reverse VAC decisions that they deem unfair.

Interviews with OVO key informants and senior managers in VAC also reflected on these expectations. These key informants expect the OVO to provide an independent voice for the fair treatment of Veterans; as well as to conduct systemic investigations on issues that affect Veterans broadly. In fact, most senior managers in VAC indicated that conducting systemic investigations is the key role for OVO as these have benefited thousands of individuals. OVO respondents also noted that the OVO is restricted in terms of addressing ‘unfair’ VAC decisions for Veterans to health care supports and some Veterans’ well-being programs/services. Considering these restrictions, the fact that many groups advocate for Veterans (e.g., RCL), and the new programs in VAC (e.g., from Budgets 2016 and 2017) to better respond to Veterans’ needs, some VAC senior leaders questioned the ongoing need for the OVO beyond conducting systemic investigations. However, all Veterans interviewed mentioned the need for an Ombudsman to investigate their complaints.

Overall, both internal (OVO) and external key informants, as well as documentary sources, indicated that the Veterans review and appeal system is not Veteran-centric and is complex and slow. The Veterans benefits review and appeal system has evolved over time and includes two levels of departmental review, the Veterans Review and Appeal Board (VRAB), as well as the OVO (see Figure 1). Also, there is an Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence (DND) and the CAF, which has a clearly distinct role from the OVO, but the different responsibilities are not clear to all Veterans, particularly if an issue occurs when the service member is leaving the CAF. Some Veterans expressed strong concerns regarding VAC’s appeal/review system, which they consider deeply flawed and stressed that the OVO needs more independence, needs unrestricted consultation with Veterans and the public, and needs to be able to mediate. A few Veterans also suggested that the OVO act as an arbitrator to avoid costly court cases.

Diagram 5: VAC Veterans Review and Appeal Ecosystem

Diagram 5: VAC Veterans Review and Appeal Ecosystem

This diagram depicts the Veteran’s benefit review and appeal ecosystem. It shows the different levels of appeal within VAC and VRAB as well as the roles of BPA, the Ombudsman, the Minister/MPs and the Federal Court.

Department

Levels of appeal within VAC are broken into two streams:

- disability benefits; and

- other benefits.

Disability Benefits

The diagram shows that those dissatisfied with a departmental decision for disability benefits can request a departmental review (first level of redress). It indicates that the Bureau of Pension Advocates has a role in referring Veterans back to the department for a departmental review or for guiding the Veteran through the three levels of VRAB redress: review, appeal, and reconsideration. Upon an unsuccessful VRAB appeal or reconsideration, the diagram shows the Veteran has 30 days to initiate a judicial review by the Federal Court.

Other Benefits

The diagram shows that there are two levels of appeal within the department for Veterans dissatisfied with a departmental decision unrelated to disability benefits: N1LA and N2LA. It also shows that Veterans have 30 days to request a first level appeal after the initial decision and thirty days to request a second level appeal after a decision is rendered on first appeal. After an unsuccessful second level appeal, a judicial review may be sought before the Federal Court.

Minister/MP

The diagram shows that the Minister of Veterans Affairs can render decisions on the Minister’s Own Motion.

Veterans Ombudsman

The role of the Veterans Ombudsman is depicted in the diagram as addressing compelling complaints arising from the adjudication and redress process within the department, and also addressing systemic issues arising from the departmental and VRAB appeal process.

Source: OVO ‘VOAC Deck’.

The Order in Council (OIC) requires that a Veteran should exhaust all levels of appeal first before coming to the Ombudsman except in compelling circumstances. However, the OVO noted that even if a Veteran exhausts all their level of appeals, the ability to redress the complaint further becomes a problem as VAC uses the legal argument that they have no authority to pursue the complaint further even if the Ombudsman puts forward a strong case to do so. As a result, Veterans noted that they are frustrated and caught in a confusing review/appeal system.

The comparative assessment sought insights from other Ombuds offices about the optimal process for departmental review of complaints prior to intervention by an Ombudsman. Most noted that Ombudsman offices should have the power to review any complaint, regardless if it has gone through a department service complaint process first. While it was noted that departments should continue to have internal complaints review processes so that they first try to address the issue, the Ombudsman should have the power to look at any complaint and not be restricted (with some specific exceptions like legal opinions), particularly when the department fails to respond to the complainant’s request for an internal review.

In the comparative assessment, all Ombudsmen also indicated that systemic investigations are critical to the work of an Ombuds office and may be even more powerful than responding to individual complaints in terms of leading to positive change for many Veterans/clients by addressing the root causes of complaints/issues.

3.3.2 Changing Context

Finding 12: While most complaints from Veterans to the OVO focus on the turnaround time for disability benefits decisions, there are a range of issues affecting Veterans that are varied and more complex since the war in Afghanistan, including mental health.

The documents reviewed indicate that the most common issues affecting Veterans have remained fairly constant over the last five years. OVO Annual reports indicate that the largest percentage of issues/complaints received from 2014/2015 to 2018/2019 related to disability awards and the turnaround time in getting decisions on these awards from VAC. While the OVO has made VAC aware of these concerns and conducted a systemic investigation on this issue, it is not able to resolve these complaints/issues for Veterans as the decisions are not within the OVO’s mandate. However, OVO documents also highlight other Veteran issues that have evolved over time including mental health (e.g. PTSD),Footnote 16 compensation for pain and suffering (Pension for Life), health support, and family support.

OVO and VAC key informants also indicated that Veterans’ needs are varied overall but now are increasingly complex with more mental health issues. However, the data shows that over time, most complaints involve the turnaround time for disability benefits decisions. Interviews with Veterans noted a change in their needs since the war in Afghanistan, including issues of mental health (PTSD), combat injuries, and family support as many have young families. A few also mentioned other issues related to sexual abuse and adjusting to civilian life.

The case studies confirmed the trend and illustrated that complaints/issues are now more complex and can lead to VAC’s misinterpretation of legislation and policies. They also illustrated how the OVO can help lead to a positive resolution of these complex issues for Veterans.

As noted above, the recent OVO’s systemic investigation on VAC’s turnaround time (TAT) on decisions on Veterans/clients benefits applications and appeals made several recommendations to reduce TAT and improve Veterans/clients experience in the process. Interviews with OVO and VAC indicate that the number of individual complaints that the OVO receives every year would be significantly reduced if VAC were to implement the OVO’s recommendations on TAT.

3.3.3 Level of Independence

Finding 13: The various lines of evidence show that independence and the ‘perception of independence’ is critical to the credibility, trust, integrity and effectiveness of an Ombudsman. The OVO was found to operate independently, while reporting to and acting as an advisor to the Minister of Veterans Affairs. However, external stakeholders do not always perceive the OVO as independent and think that the OVO should be fully independent from VAC, (e.g., reporting to Parliament).

As well, since the OVO has a limited mandate and powers, most stakeholders think that the OVO should have a legislated mandate and expanded powers (e.g., to investigate any issue, to compel evidence) to be more relevant.

The Venice Principles and input from the comparative assessment confirm that independence is the cornerstone of an Ombudsman Office. Ideally, an Ombudsman is an independent third party reviewer with complete independence from government departments and reporting directly to Parliament. Other countries have also considered the level of independence that is optimal for an Ombudsman and the Venice Principles recommend “a firm legal basis for Ombudsman Institutions, preferably at the constitutional level and/or in a law which defines the main tasks of such an institution, guarantees its independence and provides it with the means necessary to accomplish its functions effectively”. The Venice Principles also recommend that the Ombudsman ‘be elected or appointed according to procedures strengthening to the highest possible extent the authority, impartiality, independence and legitimacy of the Institution’ and ‘preferably be elected by Parliament’.Footnote 17

The OIC indicates that the OVO is a special advisor to the Minister of Veterans Affairs (reporting directly to and accountable to the Minister), its employees are employed by VAC, and VAC provides internal services to the OVO. However, based on the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and Service Level Agreements (SLAs) between the OVO and VAC, the OVO has the authority to operate independently.

Most key informants from VAC and OVO agreed that the OVO operates independently despite its reporting structure to the Minister. However, most external stakeholders questioned the independence of the OVO while being employed by and reporting to VAC. Most Veterans and other stakeholders interviewed believe that the OVO should be totally independent from VAC to avoid misperceptions, to safeguard against interference by the Minister/department, and to allow the Office to use more than just ‘moral-suasion’ to achieve results. The majority of Veterans interviewed and OVO respondents favoured full independence and increased powers for the OVO (e.g. compel evidence). Suggestions to address this included being established as a Parliamentary Officer and/or have a legislated mandate with expanded powers (e.g., to respond to any Veterans’ issue, to mediate disputes, and to legally compel evidence).

A few Veterans and other stakeholders noted that this more independent structure could lead to a more adversarial relationship with VAC and may hinder the OVO’s ability to have recommendations acted upon. A few VAC and OVO respondents also mentioned the benefits of being affiliated to the department: an enhanced understanding of the services provided (the ‘business’ of the department); and, greater ability to build relationships with departmental decision-makers to ensure mutual respect and to make an impact. However, it was acknowledged that the perception of independence is critical as clients have to view the Ombudsman as independent from the department to ensure confidentiality and trust.

Historically, as detailed in the comparative assessment, the 2007 Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs (AVCA) recommended that the OVO be established by new legislation and report to Parliament to ensure independence. Instead, the OVO was established by an Order in Council, reporting to the Minister, with the mandate and limitations noted in the OIC. Key informants in VAC and the OVO indicated that the current mandate and structure resulted since the office was established expediently, under pressure, and therefore ‘bolted on’ to VAC.

In comparing the mandate and powers of the OVO with what was recommended by AVCA in 2007, it is clear that there are key differences in two areas. Contrary to what ACVA originally intended, the OVO lacks:

- The mandate scope to address “all issues pertaining to the care, support, and benefits for all Veterans, their families, and any client of VAC, without limitations”; and,

- “Full access to documents, individuals and groups in any department including power to subpoena”.

This means that the Ombudsman has to rely on maintaining a good working relationship to obtain the necessary information to investigate complaints or identify systemic issues. While moral suasion and maintaining an amicable relationship with government departments is key to the effectiveness of any Ombuds office, regardless of its level of independence, this requirement results in a ‘complicated dance’ between the OVO Ombudsman and VAC’s senior management, as the comparative assessment and a few key informants pointed out. This reliance poses a risk to the effectiveness of the OVO if the working relationship worsens, and, as interviews with Veterans revealed, some question the OVO’s effectiveness because of this risk.

While the OVO structure is mirrored in other federal Ombuds offices, provincial and other international Ombuds institutions have been established as officers of the Legislative Assembly and independent of government and political parties, and have much broader mandates than the OVO. Table 6 below compares Ombuds institutions against the Venice Principles relating to independence and shows that the OVO and other Canadian federal Ombuds institutions have less independence than others.

| Venice Principles on Ombuds Institutions Independence European Commission | Provincial/ Territorial Ombuds InstitutionsFootnote 18 | Federal Ombuds Offices (United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and the European Union) | Canadian Federal Ombuds Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legislated Mandate - preferably | ✓ | ✓ | X |

| Ombud shall preferably be elected by Parliament | ✓ | ✓ | X |

| The Ombud shall have discretionary power on his or her own initiative to investigate cases | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ (for systemic investigations) |

| The Ombud shall have the power to interview or demand written explanations | ✓ | ✓ | X |

| The Ombud shall report to parliament on the activities of the institution | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Other Ombudsmen surveyed as part of the comparative assessment indicated that the following powers are required for an effective office:

- Power to compel evidence, and have direct access to information. Note that only some Ombudsman offices in Canada (e.g., provincial Ombudsman offices) have this power (not most federal ombudsman offices).

- Power to conduct systemic investigations and determine the topics for those investigations. Most Ombudsmen, including the OVO, have this power and it is deemed to be a critical role. It is also important to have the power to follow up on the implementation of recommendations, as the OVO does.

- Power to provide some binding recommendations, with the focus on using powers of persuasion. Note that no Ombudsman office surveyed had this power and a number did not want this power (felt it was not appropriate).

The Venice Principles, which are considered the standards for Ombuds institutions, recommend that the Ombudsman ‘have a legally enforceable right to unrestricted access to all relevant documents, databases and materials, including those which might otherwise be legally privileged or confidential. This includes the right to unhindered access to buildings, institutions and persons, including those deprived of their liberty.’Footnote 19 Furthermore, it notes that the ‘Ombudsman shall have the legally enforceable right to demand that officials and authorities respond within a reasonable time set by the Ombudsman.’Footnote 20 It should be noted that the Ontario Ombudsman, for example, has these powers.