Thousands Volunteer

The First World War

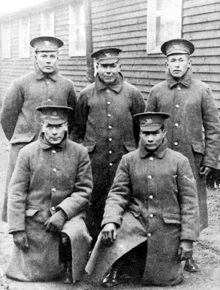

Joseph Bomberry (left) and George Buck, from the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve, were two of at least 4,000 Indigenous people who left their homes to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the First World War.

(Woodland Cultural Centre)

For four short years our sons fought in European trenches beside their sons, our blood mingled with theirs, as for four hundred years in a different way our bloods had mixed. Four thousand of our Native brothers and now grandfathers saw the European homeland through the sights of rifles and the roar of cannon. Hundreds are buried in that soil, away from the lands of their birth. These Native warriors accounted well for themselves, and the Allied cause. . . .They were courageous, intelligent and proud carriers of the shield.6

The Response

One in three, was the proportion of able-bodied First Nations men, of age to serve, who enlisted during the First World War.7 Many Indigenous people lived in isolated areas of the country, where the guns of Europe were especially distant. Yet, approximately 4,000 Indigenous people left their homes and families to help fight an international war that raged in European battlefields.

One year into the war, Duncan Campbell Scott, the Deputy Superintendent General of the Department of Indian Affairs, reported the First Nations response:

I have pleasure in drawing attention to the fact that the participation of Great Britain in the war has occasioned expressions of loyalty from the Indians, and the offer of contributions from their funds toward the general expenses of the war or toward the Patriotic Fund. Some bands have also offered the services of their warriors if they should be needed.8

Scott would make similar statements in Indian Affairs' annual reports for the next five years, as his employees across the country noted increases in both the number of First Nations recruits and the amount of money donated by reserve communities.

James Moses of Ohsweken, on the Six Nations Reserve, served in both the infantry and air services. In 1918, the aircraft from which he was observing was shot down over France. Both pilot and observer were reported missing in action. (Russ Moses)

Despite these reports, the total number of Indigenous volunteers is unknown.9 In late 1915, regional officials of the Department of Indian Affairs were instructed to complete and submit "Return of Indian Enlistments" forms. However, in his annual reports, Scott stated that not all of the recruits had been identified. Furthermore, since his department's main concern was First Nations peoples, its records rarely took into account the number of Inuit, Métis and other Indigenous people who signed up. Enlistments in the territories and in Newfoundland (which had not yet entered Confederation) were also not recorded. It is safe to say that more than 4,000 Indigenous men and women enlisted.

The Canadian Government, headed by Prime Minister Robert Borden, had not expected that so many Indigenous people would volunteer. At first, it had hoped to discourage Indigenous enlistment and initially adopted a policy of not allowing these recruits to serve overseas. The policy stemmed from a belief that the enemy considered them to be "savage," and a fear that this stereotyped view would result in the inhumane treatment of any Indigenous people who were taken prisoner.10 However, the policy was not strictly enforced and was cancelled in late 1915 because of the large number of enlistment applications from First Nations people, as well as the Allies' pressing need for more troops.

Support from Indigenous communities for the Allied war effort was by no means unanimous. For example, some band councils refused to help the Allied war effort unless Great Britain acknowledged their bands' status as independent nations. Such recognition was not granted.

Additionally, following the Canadian government's introduction of conscription—compulsory military service—in August 1917, many Indigenous leaders insisted that their peoples should be excluded. In the past, during the negotiation of treaties, some Western chiefs had requested and received assurances from the British Government that First Nations people would not have to fight for Great Britain if it entered into a war.11 The government was reminded of these promises many times and, in January 1918, exempted these recruits from combatant duties through an Order-in-Council.

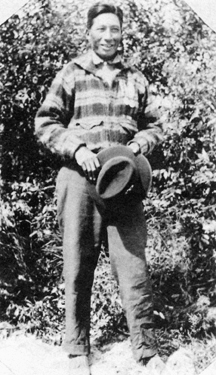

Five First Nations volunteers from Saskatchewan. Joseph Dreaver (back row, far left) later became chief of the Mistawasis Band and would volunteer to serve in the Second World War as well, as would Louis Arcand (front row, right) of the Muskeg Lake Band.

(Gladys Johnston)

On a voluntary basis, however, the enthusiasm of the Indigenous population for the war effort was evident across Canada. Some reserves were nearly depleted of young men. For example, only three men of the Algonquin of Golden Lake Band who were fit and who were of age to serve remained on their reserve.12 Roughly half of the eligible Mi' kmaq and Maliseet men of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia signed up, and, although small, Saskatchewan's File Hills community offered practically all of its eligible men. In British Columbia, the Head of the Lake Band saw every single man between the ages of 20 and 35 volunteer.

In Winnipeg, one newspaper reported that "thirty descendants of Métis who fought at the side of Louis Riel in 1869-70 . . . have just enlisted at Qu'Appelle. They are all members of the Society of French-Canadian Métis of that place. Their names are inscribed on the [Society's] roll of honour."13

News of the war did not easily reach some Canadian Indigenous communities. Reserves in the Yukon and Northwest Territories and in northern sections of the provinces had fewer transportation and communication links with the rest of Canada. People living in these areas were often unaware of the war or were unable to enlist without great effort. Nevertheless, at least 15 Inuit—or people having some Inuit ancestry—from Labrador joined the 1st Newfoundland Regiment.14 As well, approximately 100 Ojibwa from isolated areas north of Thunder Bay, Ontario, made their way to the nearest recruiting centre, in Port Arthur or Fort William.15 Many of them served in the 52nd Canadian Light Infantry Battalion—and at least six were awarded medals for bravery.

One recruit with the 52nd, William Semia, a trapper for the Hudson's Bay Company and a member of the Cat Lake Band in Northern Ontario, spoke neither English nor French when he enlisted. Undeterred, he learned English from another First Nations volunteer and later was often responsible for drilling platoons.

William Semia spoke no English when he joined the 52nd Battalion. He learned the language from another Indigenous volunteer and later used it to drill platoons. (Library and Archives Canada/C-68913)

Although its council opposed reserve enlistment, the Iroquois Six Nations of the Grand River south of Brantford, Ontario, provided more soldiers than any other Canadian First Nation. Approximately 300 went to the front. In addition, members of this reserve, the most populous in Canada, donated hundreds of dollars to help war orphans in Britain and for other war-relief purposes.

Many of the Six Nations volunteers were originally members of the 37th Haldimand Rifles, a regiment in the non-permanent active militia based on the reserve. It provided most of the members of the 114th Canadian Infantry Battalion, which had recruited throughout the area. Joining the Grand River volunteers in this battalion were 50 Mohawks from Kahnawake, Quebec, and several Mohawks from Akwesasne. Some Indigenous people from Western Ontario and Manitoba also became members. In the end, two of its companies, officers included, were composed entirely of First Nations members. In recognition of its large Indigenous make-up, the battalion adopted a crest featuring two crossed tomahawks below the motto, "For King and Country." As well, members of the Six Nations Women's Patriotic League embroidered a 114th flag, which they adorned with Iroquoian symbols.

Soon after it arrived in Great Britain in 1916, the 114th was disbanded to serve as reinforcements. Several of its members ended up with the 107th Battalion, a Winnipeg unit that went overseas with hundreds of First Nations members from the Prairies and became first a pioneer battalion16 and then part of an engineering brigade composed of more than 500 Indigenous members.17

The Six Nations Women's Patriotic League embroidered this flag for the 114th Canadian Infantry Battalion. The battalion had permission to carry it along with the King's colours and their regular regimental colours.

- Date modified: