History - Jewish Canadian service in the Second World War

Index

Overcoming challenges

Being Jewish in a Canadian society—and military—that was predominately Christian brought with it a number of challenges. The Canada of the late 1930s and 1940s was not as inclusive as it is today. There were quotas for Jewish students in many of our country’s universities, for example, as well as open discrimination in hiring for many fields of work. The tragic story of the MS St. Louis, a ship carrying more than 900 Jewish passengers from Germany seeking refuge from the persecution they were facing at home, was sadly illustrative of the anti-Semitic attitudes all too prevalent in Canada at that time. The ship was turned away from our shores and those on board forced to return to Europe where many would ultimately perish in Nazi concentration camps.

This was the larger backdrop against which many Jewish Canadian volunteers would encounter official and unofficial anti-Semitism after showing up at their local recruiting offices. It sometimes took considerable perseverance just to get into uniform, with some branches of the military presenting more barriers than others. Sadly, the experiences of young Monte Halparin of Winnipeg (who would go on to fame as a game show host with the stage name Monty Hall) were not unique. When he tried to enlist in the armoured corps at the University of Manitoba campus, he was told, “I don’t think they’re taking Jews.”

The Royal Canadian Air Force initially had a policy that expressly limited enlistment to recruits who were “of pure European decent and British subjects.” These guidelines were sometimes used to reject Jewish and other racialized volunteers outright (especially those who had not obtained their naturalization documents) before those discriminatory regulations were lifted in 1942. This was compounded by a strong British tradition and class consciousness in the air force that generally made it difficult for those of non-British origin to join or rise in the ranks. Despite these conditions, nearly 6,000 Canadian Jews served in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

The evidence suggests that the Royal Canadian Navy was the most difficult branch for Jewish volunteers to join. Fewer than 600 Canadian Jews were accepted into this branch of the military. Initially, it had restrictive recruiting policies similar to those of the air force. This was compounded by enduring ties to Britain’s Royal Navy and outmoded attitudes towards different social classes that made entry into the officer ranks particularly challenging for Jewish Canadians who wanted to take on leadership roles. Young Jewish men, like Edwin Goodman and Ben Dunkelman of Toronto, were turned away by the navy, despite being excellent potential candidates.

Indeed Dunkelman, an alumnus of the prestigious Upper Canada College and heir to the wealthy family that owned Tip Top Tailors, was a recreational sailor with his own yacht on Georgian Bay, but even that prior experience did not overcome the discrimination of the navy recruiting office.

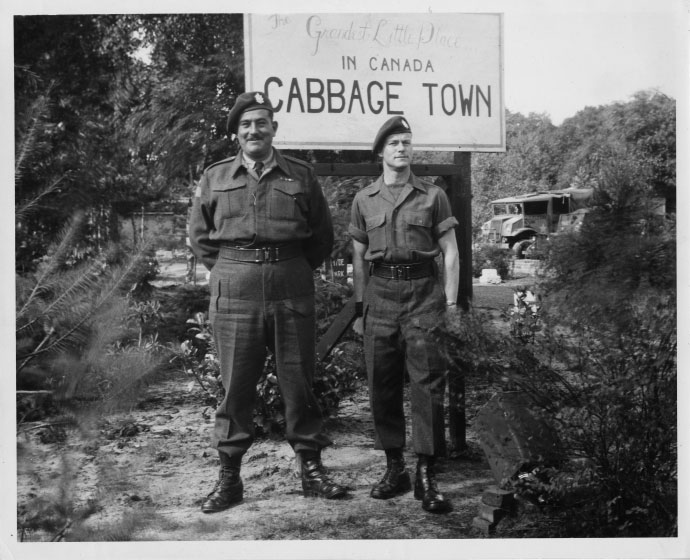

The Canadian Army presented the fewest official barriers to young Jewish men and women who volunteered or were called up to serve their country in uniform. That being said, even after having navigated the potential pitfalls to successfully enlist in any branch of the military, Jews often encountered anti-Semitic attitudes in some of their fellow service members. At times, insults and arguments and even physical fights ensued as hateful beliefs bubbled to the surface and some Jews defended themselves. It must be noted, however, that Jewish Veterans remarked that despite encountering prejudice during their time in uniform, it seldom came from those with whom they directly served alongside. The stresses of the battlefield or being in a bomber thousands of metres above enemy territory had a way of bringing together even the most diverse group of men and making perceived differences melt away.

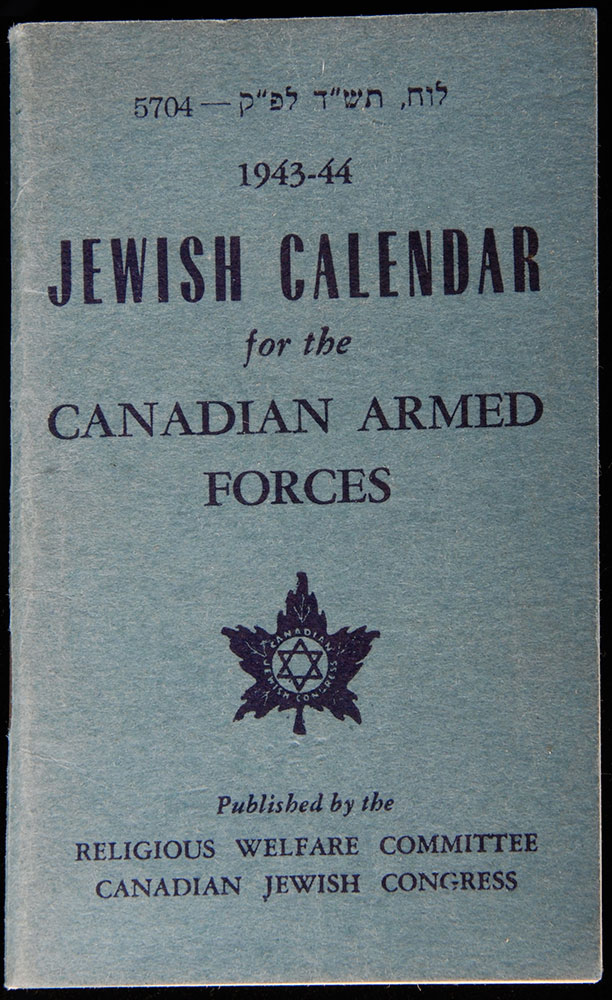

Other subtle and not-so-subtle burdens would be felt by Jewish service members when it came to the observance of their personal religious faith. Although there were ultimately 16 rabbis among the chaplains of the Canadian military, weekly Sunday Catholic and Protestant church services were the only options at many bases, and sometimes Jews would be pressured to also attend or suffer punishment by their superiors for refusing. Getting leave for major Jewish holidays or otherwise marking these special events was another challenge early in the war, but by 1943 allowances were often made to let Jewish service members properly observe them, either on base or in nearby synagogues.

When possible, the Jewish chaplains and service members would hold religious burial rites for the fallen of their faith. Their military headstones were marked differently than those of their non-Jewish comrades in cemeteries at home and overseas. From single graves of Jewish Canadians buried in far-off places such as Ghana and Sudan, to larger groupings in sprawling Canadian war cemeteries like Bény-sur-Mer near Juno Beach and Cassino in Italy, the majority of their headstones are engraved with the Star of David (although several Jewish men were buried under crosses by mistake). In addition, the gravestones typically have Hebrew lettering at the bottom which means, “May their souls be bound up in the bonds of eternal life.”

Another more logistical challenge that Jewish service members faced was trying to follow the guidelines of a kosher diet. Many Jewish Veterans of the Second World War would speak of the hard choices this entailed. Although the military did very little itself to accommodate these dietary restrictions, the Canadian Jewish community supplemented the food offerings with occasional food baskets and home-cooked meals at synagogues. Local Jewish communities from Vancouver to Halifax also operated Jewish Servicemen’s Clubs or canteens where personnel could get a kosher meal, and the Jewish chaplains distributed food like matza (unleavened bread) to troops on the front line, especially during religious holidays such as Passover. While many Jews just avoided the non-kosher offerings as best they could, some would come to accept the hard reality that they would have to bend the rules or go hungry in a military where food like pork was frequently on the menu.

The broader military experiences of Jewish service members largely mirrored that of their gentile comrades, but the twisted beliefs of the enemy they were fighting meant they had an additional chilling burden to consider—what would happen if they were captured? The extent of Nazi Germany’s abhorrent policies against Jews were well known by the time the Allies landed in Normandy, and Canadians of that faith were understandably very worried of the treatment they would face if they became prisoners of war. Understandably, some recruits chose to not cite their religion as Jewish during the enlistment process to make it harder for potential captors to know their roots. Others decided to change their names, such as George Holidenke of Montréal who enlisted as George Holden, while some, like Saul Shusterman of Toronto, discarded their identity disks (commonly known as dog tags) indicating their religion before being captured.

This was not merely a hypothetical situation; an estimated 85 Jewish Canadian servicemen became prisoners of war during the conflict. They often indeed did their best to keep their religion a secret but some, in an act of pride and defiance, even directly informed their camp guards. Sometimes their non-Jewish fellow prisoners of war would intervene to keep their Jewish bunk mates from being separated and potentially shipped to concentration camps.

- Date modified: