Joined

1983

Deployments

- Persian Gulf War based in Doha, Qatar

- Task Force Aviano, Italy (Op Echo)

- 4 rotations to Afghanistan

- OP Lobe Sigonella, Italy

- Op Impact Akrotiri, Cyprus

When Maria Vidotto joined the Canadian Armed Forces in 1983, there was no grand strategy, family pressure or dramatic calling.

It was a Yellow Pages ad in a St. Catharines, Ontario, phone book that caught her eye.

“I was a good student,” she said matter-of-factly. “I had options.”

An aptitude for mechanics

Her initial plan was to become a military police officer, but she started realizing her aptitude was leaning toward the Royal Canadian Air Force, into a trade few civilians ever see up close: Air Weapons Systems Technician.

It was a role that put her in the middle of the machinery of war—missiles, bombs, aircraft weapons systems—long before she experienced life in a theatre of it.

“We dealt with all of the weapons and support equipment on the Air Force side,” she explained.

After basic training, Vidotto was posted to CFB Bagotville in Saguenay, Québec, for on-the-job training. Then, when her one-year Youth Training Employment Plan ended, she was offered a Regular Force contract and a posting back to the same base in the same role. Her first deployment was to Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Goose Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador, where she serviced weapons and support equipment on the flight line. It was real work, but still far from the intensity that would later define her career.

Overseas deployment

That changed in 1988, when she was posted overseas to CFB Baden-Soellingen, Germany, to serve with 439 Squadron.

At the time, it felt like winning the lottery.

“I was very pleased to get that posting. I saw it as a European vacation. I knew I’d be working, but I’d have the chance to travel on leave. I was putting my training to real-world use—but war wasn’t really a factor in my thinking.”

Germany in the late Cold War was a strange mix of routine and readiness. NATO bases were built not just to operate aircraft, but to survive the opening hours of a potential nuclear conflict. Beneath the forests and airfields were hardened bunkers. They were reinforced concrete structures designed to withstand blast shock, protect aircraft components, house personnel and keep operations running under nuclear, chemical or biological threat.

“It was Cold War infrastructure,” she said. “Everything was designed for the possibility that things could go very bad, very fast.”

For a while, life settled into a rhythm of military training, aircraft maintenance, exercises and time off to travel in Europe.

War begins

“Then the real world came knocking,” she said.

When Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, the geopolitical balance the Cold War had been maintaining was thrown off.

Vidotto’s squadron was told they were deploying.

“It was basically every able-bodied person,” she recalled. “A few people took conscientious objector status and dropped out. But most were willing to go. This was what we’d been training for.”

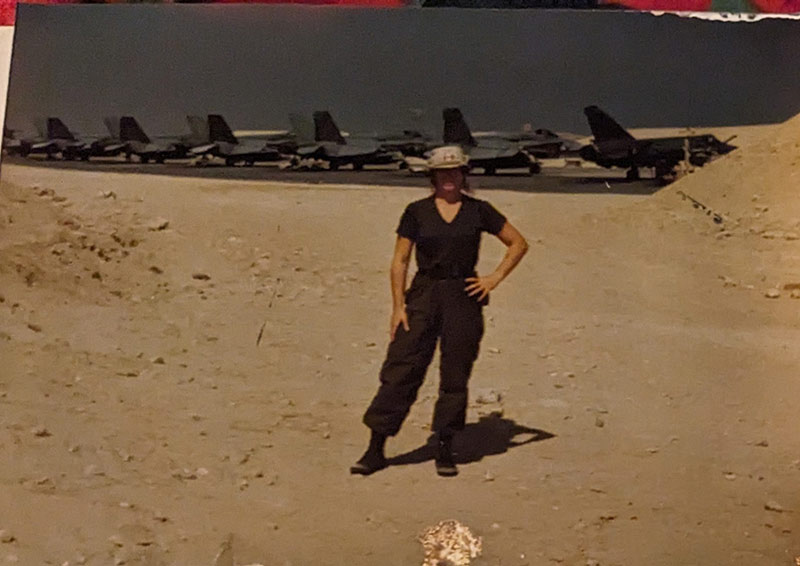

Vidotto stands in front of the flight line in Doha, Qatar, during the Gulf War.

They deployed to Doha, Qatar, part of Canada’s contribution to the coalition force during the Persian Gulf War. In the early 1990s there were no smartphones, social media or 24-hour news feeds.

“We weren’t boots on the ground in Kuwait,” she said. “We were a step removed. The Army handled security for us back then. I wasn’t fully aware of what everyone else was engaged in.”

What they knew came from command briefings—and alarms.

The camps they lived in were run-down buildings hastily modified and repaired by Army engineers. They were shacks in the desert, with running water and electricity, but no real electronic infrastructure.

“We were more or less in the dark,” she said. “We focused on the big picture, not what was right in front of us.”

She vividly remembers the day a group of reinforcement personnel arrived.

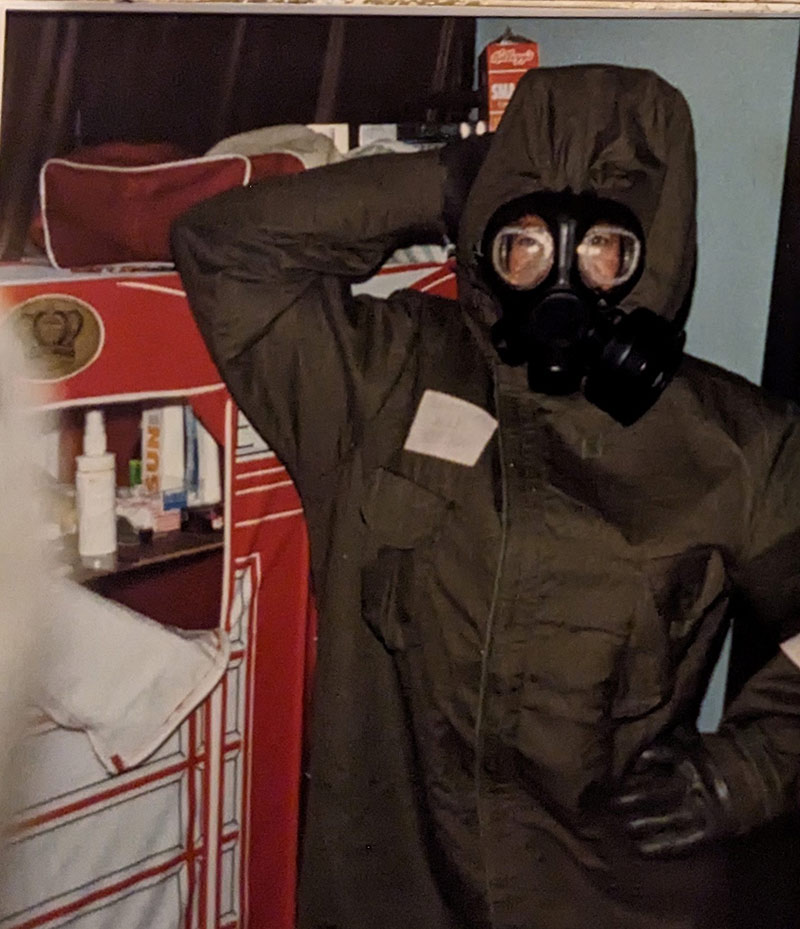

Maria Vidotto wearing chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) protective equipment in Doha, Qatar.

They had only been in theatre for a few weeks when a plane carrying support personnel was inbound to Doha airfield. Vidotto and others were on the tarmac to meet them. As the aircraft approached, Scud missile alarms began to pierce the desert air.

“We were already wearing full CBRN gear,” she said. “They are landing there for the first time and they see everyone running around in gas masks,” she laughed. “Their eyes were like saucers. We were all like, ‘Welcome to Doha!’”

Extracurricular activity

Despite the threats, military life continued as normal.

On her days off, she learned to swim at a Doha hotel pool, she worked out, played volleyball and led aerobics classes. She loved writing letters, many of them replies to Canadian schoolchildren who had written to her squadron.

No matter where they went, though, they carried their protective gear with them.

“You never went anywhere without your gear,” she said. “Even on public transport.”

Her work kept her on the deafening flight line, wearing ear defenders, loading weapons, diagnosing snags and fixing aircraft under pressure. Large coalition aircraft cycled through Doha constantly. The pace intensified once the air war began.

“We had hot lines and cold lines,” she explained. “Once the war started, both were in play. We had to have half a dozen planes ready to go, at all times.”

Their targets were clear. The mission was focused.

“Our line of attack was concentrated,” she said. “Mostly lines of Iraqi war vehicles.”

The war ends

By late February 1991, just days before the war ended, her rotation in theatre was over and she was flown back to her home unit in Germany.

“I was disappointed to leave,” she admitted. “Once you’re in it, you want to see it through to the end.”

“I was glad to have been part of it,” she said. “I felt lucky to be doing something good. I’ve always wanted to be where the action was, where the work was. I was in the right place at the right time.”

She was selected to return to Canada briefly for a Gulf War parade. Standing in uniform, she saw a banner in the crowd accusing coalition forces of being “baby killers.”

“It stays with you,” she said quietly.

Injuries and rehab

Her career continued across decades of modern conflict: tours in Italy in support of Yugoslavian/Kosovo conflict, Afghanistan, Cyprus. She deployed repeatedly, often returning injured.

Maria Vidotto is centered in a photo montage from her service in Operation Echo Aviano, Italy.

She suffered an ACL tear in 1987 and then herniated discs in her back from loading equipment in Aviano, Italy, which led to the medical evacuation she found deeply humiliating. Knee and back surgeries accumulated over the years, but she kept going.

“With injuries, the only way to keep going is to keep moving,” she said. “I’m always rehabbing. You have to keep active. If you don’t move, you die.”

When Canadian Forces fitness standards changed to emphasize lifting and dragging, her service-related injuries finally caught up with her.

“I couldn’t do it,” she said simply.

She extended her service by three years, transitioning into computer and IT systems work that she discovered she was quite good at. In May 2018, she was medically released after nearly 35 years of service, retiring as a Warrant Officer.

Today, Maria faces her hardest fight yet: stage 4 metastatic melanoma.

“They’re trying to buy me time,” she said calmly. “That’s the way the cookie crumbles.”

She still lives fully; walking, kayaking, riding horses and swimming. The same true grit that carried her through deployments carries her now.

“The endorphins help,” she said. “You just keep going. I am grateful for every day that I’ve been on this earth, and I will continue to be grateful for each new day.”

With courage, integrity and loyalty, Maria Vidotto is leaving her mark. She is a Canadian Armed Forces Veteran. Discover more stories

The well-being of Canadian Veterans is at the heart of everything we do. As part of this, we recognize, honour and commemorate the service of all Canadian Veterans. Learn more about the services and benefits that we offer.

If you are a Veteran, family member or caregiver, the support of a mental health professional is available anytime at no cost to you. Call 1-800-268-7708.