The Santa tracker

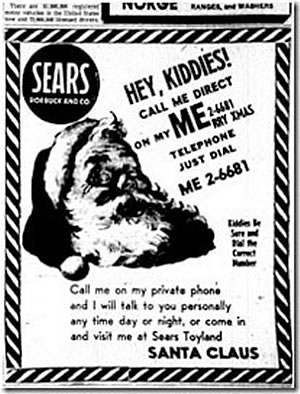

On 24 December 1955, US Air Force Colonel Shoup, Director of Operations at CONAD (Continental Air Defence Command), received a call in his office in Colorado Springs. This was no ordinary call. It was coming in on one of the top secret phone lines. Colonel Shoup answered the phone expecting it to be the Pentagon or a four-star general.

"Are you really Santa Claus?", a tiny voice asked.

It was from a little girl in Colorado Springs. She was following directions from a an advertisement that the local newspaper had run. The ad told children they could call to find out how far along Santa Claus was on his trip and it even included a telephone number. But the number printed was off by one digit and instead of connecting with Santa, the callers were coming to the Continental Air Defense Command!

Before long, the phone was ringing off the hook and Colonel Shoup, rather than hanging up, told his staff to give all the children that called in a "current location" for Santa Claus. It was the beginning of the Santa Tracker tradition. When the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD) replaced CONAD in 1958, it kept the tradition.

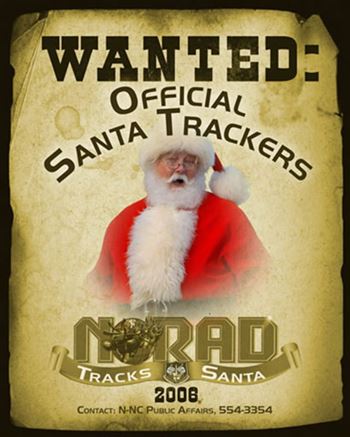

NORAD's Santa Tracker has always made use of the media__ telephone hotlines, newspapers, radio and television were utilized. From 1997 to today, the NORAD Santa Tracker has been a very popular site with millions of visitors, from more than 200 countries, watching Santa's progress on Christmas Eve through the tracker.

NORAD carries out the operation with the assistance of many corporate partners and volunteers. There are more than 1,000 volunteers that answer calls and e-mails, and update the social media sites. Over the years, these volunteers have included countless numbers of Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps personnel and their families. The Canadian NORAD fighter pilots are responsible for flying the CF-18s that welcome Santa to North America.

The program starts each year on December 1st with a "Countdown Village". It features the history of the Santa Tracker, a countdown to take-off, updates from Santa's Village, and games. On Christmas Eve, a map shows Santa's launch from the North Pole and tracks him as he makes his trip around the world.

The Christmas Truce of 1914

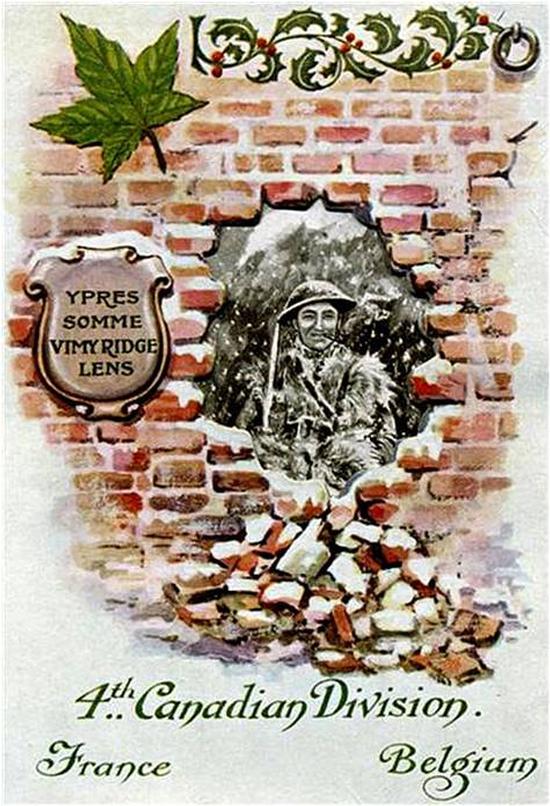

Something incredible happened on December 24, 1914. Soldiers from both sides put down their weapons, stepped out of their trenches and enemy really did meet enemy between the trenches.

The First World War had been raging for four months. The weather that December was cold and wet. Many of the trenches were continually flooded, soldiers were covered in mud and exposed to frostbite and trench foot. They were dreading having to spend Christmas away from their families. Then something incredible happened on December 24, 1914. Soldiers from both sides put down their weapons, stepped out of their trenches and enemy really did meet enemy between the trenches. For a short time, there was peace.

There were many truces along the Western Front that Christmas, but the truce was not total. Shelling and firing continued in some parts. Some of the truces had been arranged on Christmas Eve while others were arranged on Christmas Day.

There were even arrangements which included a ruling as to when the truce would end. Along many parts of the Front Line, the truce was brought about by the arrival of miniature Christmas trees in the German trenches. Jovial voices could be heard calling out from both sides, followed by requests not to fire, then shadows of soldiers could be seen gathering in no man’s land, laughing, joking and exchanging gifts. Amongst the joy, there was sadness too, as both sides used this opportunity to seek out the bodies of their dead comrades and give them a decent burial.

The Christmas Truce of 1914 was not a unique occasion in military history. It was a return of a long established tradition. It is common in conflicts with close quarters and prolonged periods of fighting for informal truces and generous gestures to take place between enemies. Similar events have occurred in other conflicts throughout history–and they continue to occur.

Christmas in Ortona

By December of 1943, the Allies had reached the historic seaport of Ortona on Italy's Adriatic coast. The town was held by Hitler's elite paratroopers, whom he had personally ordered to defend it at all costs. The Canadian troops had quickly advanced up the eastern side of Italy and would meet the Germans at the Moro River, less than seven kilometres away from Ortona. It was hoped there would be a day or so of fighting. Instead, the Canadians had to their way into the town for eight terrible days.

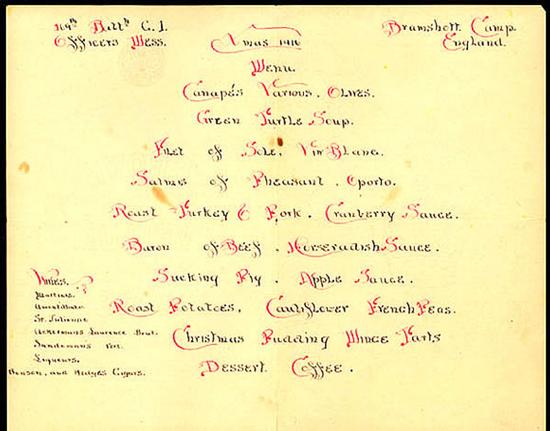

On December 25, 1943, in a bombed-out church at Santa Maria di Constantinopoli, members of the Seaforth Highlanders gathered in shifts for a Christmas dinner a few blocks from the fighting.

They had scrounged the essentials for this special meal—table cloths, chinaware, beer, wine, roast pork, applesauce, cauliflower, mashed potatoes, gravy, chocolate, oranges, nuts, and cigarettes. An organist played “Silent Night” and for a few moments there was a semblance of normality as the soldiers were able to sing these words amongst the raging war. But they had to return to the fighting. For some, it would be their last meal.

The Germans withdrew two days after Christmas. The Canadians achieved their objective, but at great cost. Ortona had been liberated, ending the month that would go down in history as "Bloody December.” It was the bloodiest month of war in the Italian Campaign with 213 Canadians killed in action during that Christmas week alone. The losses suffered by the Canadians at Ortona were nearly one quarter of their total casualties in the entire Italian Campaign.

Dear Santa

In December 1944, Thérèse Perrault was nine years old, and living in Athabaska, Quebec. Although her belief in Santa Claus was not as strong as before, she still sent him several letters all the same. But she didn't ask for gifts; she asked that he give the doll she might have received to a little girl in war-torn Europe. All she really wanted was for Santa to send news of her big brother Richard, who had gone to the front. It had been months since her family had received his last letter . . .

Dear Santa,

Before going to Midnight Mass tonight, my parents stopped to visit our neighbours, the Maheu family. Mom had made meat pies and regular pies for them. I saw the pain on their faces. They were wearing black armbands to show they were in mourning. Santa Claus, why is there so much misery in the world?

When we got to Saint-Christophe church, I prayed with all my might until my knees were sore and my hands hurt from squeezing them so tight. I was hoping that my prayers would go so high up in the sky that they would reach Baby Jesus. On this holy night, I was hoping for a miracle.

At the end of the celebration, the parishioners were invited to exchange wishes of peace, love, health and prosperity. We left the church quickly. It was hard enough as it was. But there was also another mass waiting for us at home. It was being broadcasted on national radio, from London, England.

When we turned on the radio, a man was singing "Silent Night" in French. He was just about finished …

When he was done, the announcer spoke in English, and my father translated as best as he could. We heard words like "military," "Chaudière regiment," "O Holy Night," and then I heard the most beautiful voice in the world …

It was my brother Richard who was singing! My parents didn’t believe me right away, but quickly realized I was right. It was him! IT WAS REALLY HIM!!!

We all fell silent so we could listen to the rest of the Christmas carol. "O Holy Night" never sounded so beautiful to us as that night when we heard Richard sing it across the airwaves.

Excerpt from the book Lettres de décembre 1944, by Alain M. Bergeron..

Heroes Remember

Watch and listen to Veterans sharing stories of their military service during Christmas.

First World War

Second World War

Canadian Armed Forces

Promotional video

Photo galleries

Cover of Illustrated London News, January 9, 1915. A German soldier approaches his British enemies with a lantern and a small Christmas tree and organizes a cease fire.

Photo courtesy of www.worldsecuritynetwork.com/

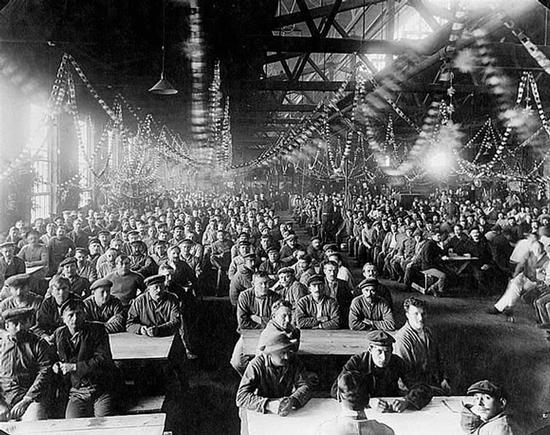

Christmas celebration at Internment Camp in Canada, W.W.I - 1916.

Photo: Internment Camps / Library and Archives Canada / C-014104

Christmas morning, 1918, in McWharrie Ward, No. 2 Canadian Stationary Hospital, near Boulogne, France.

Photo courtesy of www.maureenduffus.com / Battlefront Nurses of WWI: The Canadian Army Medical Corps in England, France and Salonika, 1914-1919First World War

Private Fernand M. Bonneau distributing bread to children attending Christmas party sponsored by the 1st Canadian Army, Tilburg, Netherlands, 24 December 1944.

Photo: Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-114066

Senior Welfare Officer Mary Scott of the Canadian Red Cross preparing Christmas basket for distribution to patients at No.10 Canadian General Hospital, R.C.A.M.C. 15 December 1944 / Tilburg, Netherlands.

Photo: Ken Bell / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-133613

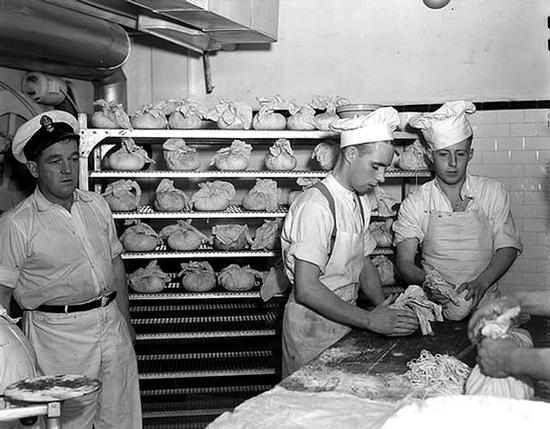

Preparations for Christmas dinner aboard HMCS Prince David. 25 December 1944 / Ferryville, Tunisia.

Photo: Canada. Dept. of National Defence /Library and Archives Canada

Personnel of 42 Company, Canadian Women's Army Corps (C.W.A.C.), hosting a Christmas party for children, England, 19 December 1943.

Photo: Lieut. Kenneth H. Hand / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-150134

Children at a Christmas party sponsored by the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, Elshout, Netherlands, 17 December 1944.

Photo: Lieut. H. Gordon Aikman / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-152495

Canadian soldiers enjoying a few drinks on Christmas Day at the front, Ortona, Italy, 25 December 1943.

Photo: Lieut. Frederick G. Whitcombe / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-163936

High School students help out during the Christmas rush at the Post Office during the Second World War. Ottawa, Ont., Nov 1943.

Photo: F.C. Tyrell / National Film Board of Canada. Photothèque / Library and Archives Canada / PA-166789

General H.D.G. Crerar with St. Nicholas (Lieutenant H.J. Tingle) and children during a Christmas party at First Canadian Army Main Men's Mess. Tilburg, Netherlands. 24 Dec 1944.

Photo: Barney J. Gloster / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-166865

Personnel of No. 2 Motor Ambulance Convoy Detachment, Royal Canadian Army Service Corps (R.C.A.S.C.), displaying toys which will be presented to Dutch children during a Christmas party, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 20 December 1944.

Photo: Lieut. Donald I. Grant / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-197000Second World War

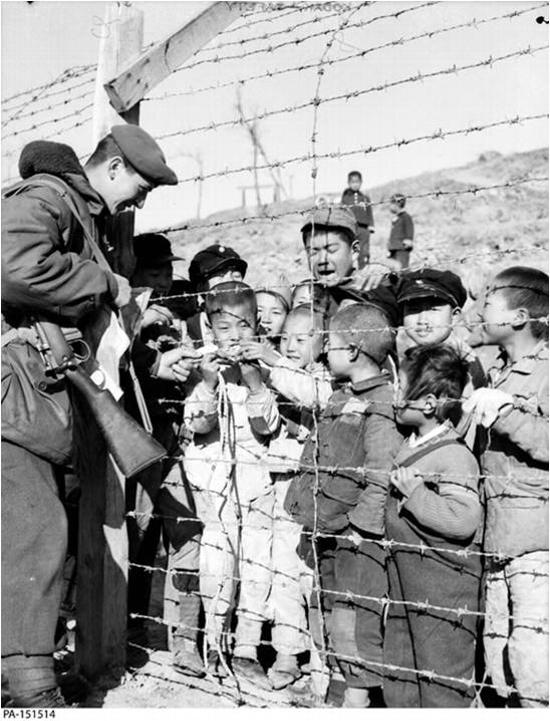

Korean youngsters fed by the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. Private Steve Towstego on guard duty passes out a leg of chicken he had saved from his dinner. Dec. 25, 1950.

Photo: Canada. Department of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-151514

First Christmas away from home for members of the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. From left to right: Sergeants J. Moore, Melnechuk and L.J. Fumano. Dec. 1950.

Photo: Bill Olson / Canada. Department of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-171314

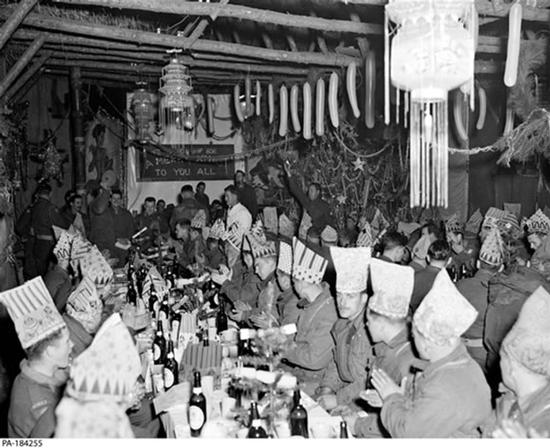

An early Christmas dinner eaten in shifts so all the infantrymen of the brigade can enjoy a traditional dinner. Also shown are Brigadier J.M Rockingham and Major-general Jim Cassels. Dec. 1951.

Photo: Canada. Department of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-184255

Members of the 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade sending Christmas greetings to Canada via NBC-TV. December 20, 1952, Korea.

Photo: George Whittaker / Library and Archives Canada / PA-128038

Christmas dinner, 3rd Battalion, Royal 22e Régiment. Dec. 24, 1953.

Photo: Butler / Canada. Department of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-193932Korean War

Soldiers of Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment Battle Group enjoy Christmas dinner at Forward Operating Base Ma'Sum Ghar, Afghanistan, on December 25, 2006.

Photo: Department of National Defence / AR2006-S003-0160 / Capt Edward Stewart, JTF-AFG Op Athena Roto 2.

Corporal Demerchant hands two Christmas presents from Canada to Master Corporal Darren Lockwood in Afghanistan on December 25, 2006.

Photo: Department of National Defence / AS2006-0963a / Sergeant Dennis Power.

A Canadian Armed Forces member from Task Force-Iraq decorates her camp in celebration of the Christmas season during Operation Impact on December 3, 2014.

Photo: Department of National Defence / GX2014-0069-018 / OP Impact.

Able Seaman Danielle Delaronde and Private Chelsie Whalen onboard HMCS Regina decorate for Christmas while deployed in the Arabian Sea for Operation Artemis on December 14, 2012.

Photo: Department of National Defence / HS2-2012-216-002 / Corporal Rick Ayer.

Sailors of HMCS Toronto celebrate a Christmas mass on December 24, 2013 during Operation Artemis in the Arabian Sea.

Photo: Department of National Defence / HS9-2013-0148-004 / LS Dan Bard, Formation Imaging Services.

Members of the Canadian Air Task Force Lithuania arrive with gifts and goods for the Šiauliai City Baby's Orphanage in Lithuania on December 18, 2014 during Operation Reassurance.

Photo: Department of National Defence / WG2014-0438-0208 3 / Air Task Force - OP Reassurance.

Canadian Forces members show off their 2010 Olympic mitts during a Canadian contingent visit for the Christmas holidays. December 25, 2009, Kandahar Airfield, Afghanistan.

Photo: Department of National Defence / AR2009-0078-173 / Cpl Owen W. Budge, Joint Task Force Kandahar Image Tech, Afghanistan Roto 8.

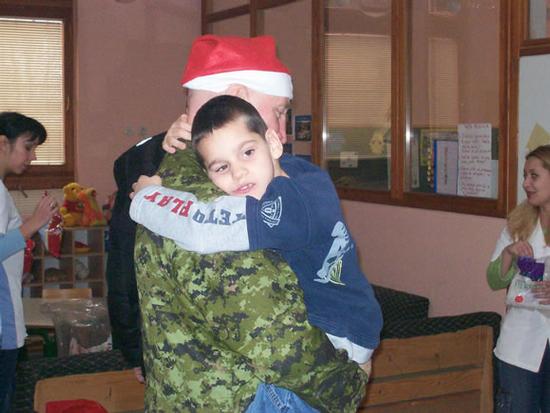

LCol Blair receives a big hug from one of the students. This is the third year in a row that the Canadian contingent has supported the Institute for Special Children's Education, Mjedenica, in Sarajevo. Presents included individual packages with toys and candy. The group also donated a Christmas tree and ornaments. It was a very worthwhile and magical experience to see the excitement shown by these young children during our visit and it made our Christmas brighter, said LCol Blair, the Acting Task Force Commander. December 24, 2007, Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Photo: Department of National Defence / NA2008-1001 / Lt Dunsiger, CJ 6 Co-ordination Officer in NATO HQ Sarajevo on Roto 6 with Op BRONZE.

Photo: Department of National Defence / HS2006-0814-02 / Cpl Rod Doucet, Formation Imaging Services Halifax

A rare site of two Canadian subs sailing together into homeport for the Christmas holidays. Seen leading the pack is the HMCS Cornerbrook with the HMCS Windsor following. December 21, 2006, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The ship's company of HMCS Montreal gathered on the flight deck with honoured guests, including Her Excellency the Governor General Adrienne Clarkson on Christmas Day. HMCS Montreal is operating in and around the Arabian Sea as part of Operation Apollo, Canada's military commitment to the international campaign against terrorism. December 25, 2002.

Photo: Department of National Defence / HS025129d62 / MCpl. Paz Quillé / Imaging Services Halifax aboard HMCS Montreal.

Mail arrives just in time for Christmas on HMCS Fredericton while on patrol in the Gulf of Aden. HMCS Fredericton is deployed on a six-month mission to the Arabian Sea, Gulf of Aden and Horn of Africa to conduct counter piracy and counter terror operations alongside our NATO and Coalition partners. December 25, 2009.

Photo: Department of National Defence / HS2009-N082-005 / Corporal Peter Reed, Formation Imaging Services, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Private Melissa Wiseman, a medic with 2 Field Ambulance stationed at Forward Operating Base Ma'sum Ghar gets into the spirit on Christmas morning and manages to get a call through to home on a satellite phone. December 25, 2006, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan.

Photo: Department of National Defence / AS2006-0930a / Sergeant Dennis Power, Army News-Shilo

Two CH-146 Griffon helicopters (call signs Rudolph and Blitzen) flies past Toronto’s CN Tower en route to the Toronto Hospital for Sick Children. The Griffon crews delivered Santa’s undercover elves and over 500 presents collected from military members and the local community to brighten the day for young patients unable to spend Christmas at home with their families. December 16, 2005, Toronto, Ontario.

Photo: Department of National Defence / FA2005-0183a / Master-Corporal Larry Wilson, 400 Tactical Helicopter SquadronCanadian Armed Forces