Joined

1987

Postings

- HMCS Athabaskan 1988-1991

- CFFS Halifax 1991-1993

- HMCS Montreal 1993-1998

- CFNOS Halifax 1998-2001

- HMCS St. John’s 2001-2004

- FMF Cape Scott, 2004-2005

- HMCS St. John’ 2005-2008

- FMF Cape Scott, 2008-2011

- HMCS Athabaskan 2011-2013

- FMF Cape Scott, 2013-2016

- DGMEPM, 2016-2018

- QAWC Costal, 2018-2022

Deployments

- HMCS Athabaskan - OP Friction

- HMCS Montreal - NATO OP Athena (Former Yugoslavia)

- HMCS St. John’s - OP Apollo

- HMCS Athabaskan - OP Caribbe

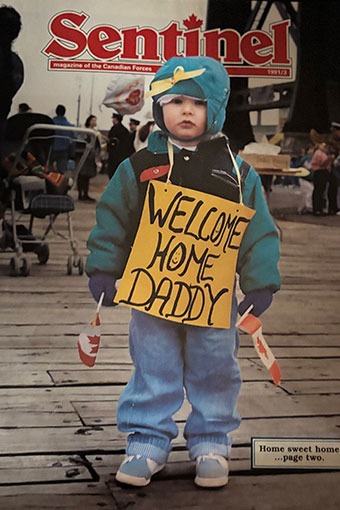

Welcoming home Daddy

It was a grey day when Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship (HMCS) Athabaskan sailed back into Halifax Harbour after months in the Arabian Gulf. The Atlantic air was heavy with mist. On the jetty, a young sailor’s family stood in the anxious crowd; a wife, parents, siblings and two small boys. One of them, barely old enough to understand what war was, clutched a handmade sign that read: “Welcome Home Daddy”.

For Leading Seaman Michael Pryor, the moment he spied them alleviated months at sea in high temperatures, sailing in a war zone near mines and the anxiety of working and sleeping below the waterline.

A Halifax Herald photographer was perfectly poised to capture Pryor’s reunion kiss with his wife Debra, which made the front page the following day. The family portrait and image of little two-year-old Anthony would land in Sentinel magazine. These family mementoes marked the beginning of Michael Pryor’s service, and seeped into the next generation.

From Truro to the Gulf

Born and raised just outside of Truro, Nova Scotia, Pryor joined the Royal Canadian Navy in 1987. He was working maintenance at a hotel when he joined the Navy for steady work and better pay. After basic training at CFB Cornwallis, he trained as a Marine Engineering Mechanic, advancing through technical trade and temporarily serving aboard ships like HMCS Annapolis before being posted to HMCS Athabaskan, an Iroquois-class destroyer.

In 1990, at just 27 years old, Pryor deployed to the Arabian Gulf as part of Operation Friction. HMCS Athabaskan sailed into a live war zone—escorting coalition vessels, protecting hospital ships and operating in waters seeded with naval mines. At one point, the ship and crew helped clear a path through a minefield after the USS Princeton struck two mines, allowing the damaged ship and tug to move south for repairs.

“That’s when it really hit me that this wasn’t an exercise,” he said.

Below decks, life was cramped. More than 50 sailors slept in triple decker bunks stacked above fuel and water tanks, below the waterline. In peacetime, three-deck hatches on these destroyers stayed open. But in a body of water strewn with mines, the safety of the vessel came before the crew’s comfort and the mess-deck hatches were shut to preserve the ship’s integrity if a mine detonated.

“You lived with the same people, day in and day out,” Pryor said. “You learned to get along. We didn’t have cell phones. We had each other, our books, our cards. That was it.”

He remembers watching Tomahawk missiles arc off American battleships just miles away. After the war, he remembers the thick, acrid air from Kuwait’s burning oil fields, so heavy with smoke and particulate that you couldn’t stay on the upper decks for long. The ship’s air filtration system’s filters had to be cleaned regularly.

Amid the danger, there was pride in the professionalism of the crew and trust in experienced shipmates and the men who sailed below.

“I felt safe with the people I was with,” he said. “They were great engineers and solid sailors.”

Perfume-scented love letters

Letters from home, which took weeks to arrive, were passed out from the mailbags on the mess decks. Pryor remembers excitedly opening envelopes that smelled like his wife’s signature “Eternity” perfume.

“I knew they were from her,” he said.

To show support for the troops, Halifax businesses sent care packages for Christmas to those serving in the Gulf. One of the packages had a bright yellow Walkman for each of them. Sailors bought cassette tapes in Middle East foreign ports. “Small things like rock and roll blasting in your earphones helped when you were 50 days at sea, setting endurance records, and pushing through the monotony and tension of wartime operations,” he said.

They didn’t talk much about the work they were doing to friends and family at home.

“Loose lips sink ships,” Pryor said. “You kept it close.”

Coming home

When HMCS Athabaskan finally returned to Halifax in the spring of 1991, families crowded the harbour’s edge. Pryor’s eldest son, Donald, was old enough to remember the day. His youngest, Anthony, was just two and a half, holding that sign he would later only know from photographs.

Pryor would go on to serve nearly 35 years. Today, he works at the Halifax Shipyard as a technical inspector of mechanical systems for the Department of National Defence. He is still keeping ships safe, still serving in a different way. He is deeply proud of his service in the Gulf, the professionalism of the sailors he served beside and his time as a member of the Canadian Armed Forces.

“Canadians need to be strong, now more than ever,” he said.

The son who followed

Anthony Pryor doesn’t remember the day his father came home. But he remembers the photos, the magazines and the stories from his childhood..

“Those pictures were everywhere,” he said. “It was a cool story growing up.”

Like most military kids, he also remembers missing his Dad during long deployments.

“I missed him a lot,” Anthony said. “That part stays with you.”

Today, Anthony wears the uniform himself. As a member of the Canadian Armed Forces, he is an Army doctor completing a two-year residency in Gander, Newfoundland and Labrador, with a focus on emergency medicine. He’s drawn to the same high-pressure environments his father navigated decades earlier at sea.

“I thrive in chaos,” he said with a laugh. “That’s where I’m at my best.”

Hearing his father talk about navigating minefields and working in a war zone made an impression on him as a kid.

“It was freaky,” he explained. “There must have been so much fear doing that. You have to respect service like that, putting yourself in harm’s way for the greater good.”

When asked about deployments, Anthony laughed.

“Honestly, I have more fear of postings than deployments. But the work? The adrenaline? That’s the right fit for me.”

Military families

For military families, service isn’t carried by one person. It lives in the waiting, the letters that smell like home, the children who grow up with stories instead of memories and the strength of spouses who keep the home fires burning.

It isn’t just about thanking those in uniform. It’s about recognizing the families who stood on the jetty in the rain. The kids who waved signs they wouldn’t remember. The partners who waited through long silences. And the generations who carry forward the pride of service - and its cost.

With courage, integrity and loyalty, Michael and Anthony Pryor are leaving their mark. They are Canadian Armed Forces Veterans and members. Discover more stories.

The well-being of Canadian Veterans is at the heart of everything we do. As part of this, we recognize, honour and commemorate the service of all Canadian Veterans. Learn more about the services and benefits that we offer.