Entitlement Eligibility Guideline (EEG)

Date reviewed: 22 January 2025

Date created: February 2005

ICD-11 code: FA33

VAC medical codes:

01341

Internal derangement knee, torn meniscus, torn cartilage knee, meniscectomy (lateral or medial)

84400

Medial and lateral collateral ligament sprain

This publication is available upon request in alternate formats.

Full document PDF Version

Definition

For the purposes of this entitlement eligibility guideline (EEG), the term internal derangement of the knee (IDK) includes conditions resulting from injury to the following key structures:

- anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)

- posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

- medial meniscus

- lateral meniscus

- medial collateral ligament (MCL)

- lateral collateral ligament (LCL).

Injury means chronic knee disorders resulting from:

- A torn, ruptured, or otherwise damaged meniscus—the cartilage that cushions the space between the bones in the knee joint.

- A partial tear (sprain/strain) or total tear of the knee ligaments—key structures in the knee that contribute to joint stability.

These conditions may be present with or without associated damage to the capsular ligament of the knee. Affected individuals may experience persistent or intermittent symptoms: pain, instability or giving way in the knee, or unusual knee movement.

Diagnostic standard

Diagnosis by a qualified medical practitioner (orthopedic surgeon, family physician), nurse practitioner, or physician assistant (within their scope of practice) is required.

Relevant investigations confirming IDK include arthroscopic examination, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Anatomy and physiology

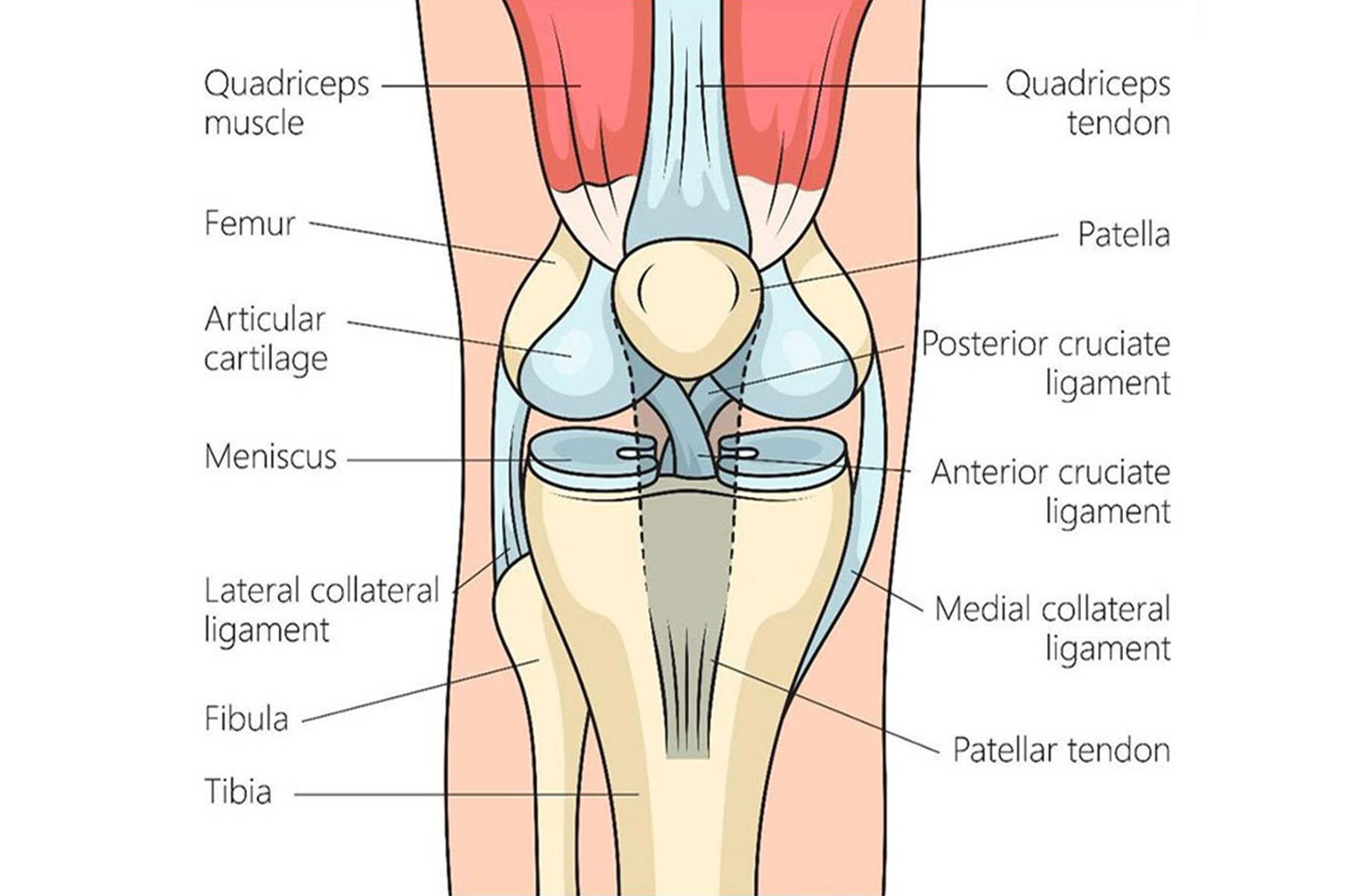

IDK refers to complex injuries of the knee, impacting the mechanisms responsible for its stability and movement. This condition may involve disruption to the meniscus, joint cartilage, ACL, PCL, MCL, or LCL (Figure 1: Knee anatomy).

Figure 1: Knee anatomy

The knee menisci are two C-shaped pieces of tough, rubbery cartilage that sit between the femur and the tibia in your knee. The menisci act like shock absorbers, cushioning the knee joint and helping to distribute weight evenly to ensure smooth movement.

A knee meniscus can tear during activities that put pressure on or rotate the knee joint (such as squatting, lifting heavy objects, or playing sports involving quick turns and stops). A torn meniscus can disrupt the normal smooth movement of the knee, leading to pain, swelling, and stiffness. The torn piece of the meniscus can also cause the knee to lock or give way during movement, limiting an individual's ability to walk or run effectively.

The knee contains two cruciate ligaments, the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), which cross each other in the center of the knee joint. The ACL runs diagonally in the middle of the knee, providing stability by preventing the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur. The PCL, located behind the ACL, keeps the tibia from sliding backward. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments are fundamental to the stability of the knee, especially the ACL.

When the ACL is damaged, it can greatly weaken the structural integrity of the knee. Such instability is often worsened by engaging in high-impact sports or having inadequate muscle strength to support the knee, hastening the degeneration of the joint. The individual's level of physical activity can hasten the progression of these injuries to degenerative conditions. Those with higher activity levels may face a faster onset of osteoarthritis due to increased stress on the vulnerable knee structures.

Joint instability can also evolve into conditions such as osteochondritis dissecans. This condition occurs when a small piece of bone begins to separate from its surrounding region due to a loss of blood supply. This can lead to pain, swelling, and difficulty moving the knee, as the loose fragment can interfere with the knee's normal movement. Osteoarthritis dissecans of the femoral condyle is one of the most common conditions which generate radiopaque osteocartilaginous loss bodies.

Clinical features

The clinical presentation of IDK, particularly when the ACL or PCL are involved, is often marked by symptoms of instability, discomfort, and limited range of motion. Individuals may report a sensation of the knee 'giving way' or locking during activity, especially in scenarios demanding pivoting or lateral movements such as sports. The onset of pain can be acute following injury or worsen over time, aggravated by continued physical exertion.

Research shows both males and females experience similar types of knee joint and tissue injuries. Females, however, are three to six times more likely to experience acute ACL types of injuries than males, and females tend to experience PCL injuries at an older age than males.

Entitlement considerations

In this section

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

For VAC entitlement purposes, the following factors are accepted to cause or aggravate the conditions included in the Definition section of this EEG, and may be considered along with the evidence to assist in establishing a relationship to service. The factors have been determined based on a review of up-to-date scientific and medical literature, as well as evidence-based medical best practices. Factors other than those listed may be considered, however consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

The timelines cited below are for guidance purposes. Each case should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and its own merits.

Factors

- Specific trauma to the knee prior to the clinical onset or aggravation of IDK.

Specific trauma means:

- Direct physical injury, such as a hit, blow, knock, or a penetrating injury from a projectile such as a bullet or shrapnel, or

- A twisting or wrenching injury involving excessive stretching or straining of the capsule or ligaments in the knee joint resulting in abnormal mobility and instability of the joint (indicated by periodic giving way or locking of the joint). Twisting injuries to the knee most commonly occur during sporting activities.

Note: Symptoms (including pain, swelling, or issues with mobility) are expected to appear within 24 hours of the injury.

- Inability to obtain appropriate clinical management of IDK.

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment

Section B provides a list of diagnosed medical conditions which are considered for VAC purposes to be included in the entitlement and assessment of IDK.

- Osteoarthritis of knee

- Chondromalacia patella

- Patellofemoral syndrome

- Patellofemoral osteoarthritis

- Baker's cyst

- Synovial plica syndrome

- Recurrent lateral dislocation of patella

- Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee

- Chronic prepatellar bursitis

- Chronic suprapatellar bursitis

Section C: Common medical conditions which may result, in whole or in part, from internal derangement knee and/or its treatment

No consequential medical conditions were identified at the time of the publication of this EEG. If the merits of the case and medical evidence indicate that a possible consequential relationship may exist, consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

Links

Related VAC guidance and policy:

- Chronic Plica Syndrome – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Osteoarthritis – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Pain and Suffering Compensation – Policies

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police Disability Pension Claims – Policies

- Dual Entitlement – Disability Benefits – Policies

- Establishing the Existence of a Disability – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Peacetime Military Service – The Compensation Principle – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Wartime and Special Duty Service – The Insurance Principle – Policies

- Disability Resulting from a Non-Service Related Injury or Disease – Policies

- Consequential Disability – Policies

- Benefit of Doubt – Policies

References as of 22 January 2025

Adams, B. G., Houston, M. N., & Cameron, K. L. (2021). The Epidemiology of Meniscus Injury. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, 29(3), e24–e33. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSA.0000000000000329

Aguero, A. D., Irrgang, J. J., MacGregor, A. J., Rothenberger, S. D., Hart, J. M., & Fraser, J. J. (2023). Sex, military occupation and rank are associated with risk of anterior cruciate ligament injury in tactical-athletes. BMJ Military Health, 169(6), 535–541. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2021-002059

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (1997). Statement of principles concerning internal derangement of the knee (reasonable hypothesis) (No 59 of 1997). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority (1997). Statement of principles concerning internal derangement of the knee (balance of probabilities) (no. 60 of 1997). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2019). Statement of principles concerning internal derangement of the knee (reasonable hypothesis) (No 7 of 2019). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority (2019). Statement of principles concerning internal derangement of the knee (balance of probabilities) (no. 8 of 2019). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Barbeau, P., Michaud, A., Hamel, C., Rice, D., Skidmore, B., Hutton, B., Garritty, C., da Silva, D. F., Semeniuk, K., & Adamo, K. B. (2021). Musculoskeletal Injuries Among Females in the Military: A Scoping Review. Military Medicine, 186(9–10), e903– e931. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usaa555

Briggs, A. M., Cross, M. J., Hoy, D. G., Sànchez-Riera, L., Blyth, F. M., Woolf, A. D., & March, L. (2016). Musculoskeletal health conditions represent a global threat to healthy aging: A report for the 2015 World Health Organization World Report on Ageing and Health. The Gerontologist, 56(Suppl 2), S243–S255. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw002

Canale, S. T., & Campbell, W. C. (Eds.). (1998). Campbell’s operative orthopaedics (9th ed). Mosby.

Cardone, D. A., Jacobs, B. C., Fields, K. B. (Section Editor), & Grayzel, J. (Deputy Editor). (2023). Meniscal injury of the knee. UpToDate.

Dee, R. (Ed.). (1997). Principles of orthopaedic practice (2nd ed). McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Division.

Dijksma, C. I., Bekkers, M., Spek, B., Lucas, C., & Stuiver, M. (2020). Epidemiology and Financial Burden of Musculoskeletal Injuries as the Leading Health Problem in the Military. Military Medicine, 185(3–4), e480–e486. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usz328

dos Santos Bunn, P., de Oliveira Meireles, F., de Souza Sodré, R., Rodrigues, A. I., & da Silva, E. B. (2021). Risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries in military personnel: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 94(6), 1173–1189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01700-3

Friedberg, R. P., d'Hemecourt, P. A., Fields, K. B. (Section Editor), & Grayzel, J. (Deputy Editor). (2024). Anterior cruciate ligament injury. UpToDate.

Golightly, Y. M., Shiue, K. Y., Nocera, M., Guermazi, A., Cantrell, J., Renner, J. B., Padua, D. A., Cameron, K. L., Svoboda, S. J., Jordan, J. M., Loeser, R. F., Kraus, V. B., Lohmander, L. S., Beutler, A. I., & Marshall, S. W. (2023). Association of Traumatic Knee Injury With Radiographic Evidence of Knee Osteoarthritis in Military Officers. Arthritis Care & Research, 75(8), 1744–1751. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.25072

Lovalekar, M., Hauret, K., Roy, T., Taylor, K., Blacker, S. D., Newman, P., Yanovich, R., Fleischmann, C., Nindl, B. C., Jones, B., & Canham-Chervak, M. (2021). Musculoskeletal injuries in military personnel—Descriptive epidemiology, risk factor identification, and prevention. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 24(10), 963–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2021.03.016

MacDonald, J., Rodenberg, R., O'Connor, F. G. (Section Editor), & Grayzel, J. (Deputy Editor). (2023). Posterior cruciate ligament injury. UpToDate.

McMahon, P. J., & Skinner, H. B. (Eds.). (2021). Current diagnosis & treatment in orthopedics (Sixth edition). McGraw Hill.

Miller, M. D., Hart, J. A., & MacKnight, J. M. (Eds.). (2020). Essential orthopaedics (Second edition). Elsevier.

O’Leary, T. J., Young, C. D., Wardle, S. L., & Greeves, J. P. (2023). Gender data gap in military research: A review of the participation of men and women in military musculoskeletal injury studies. BMJ Military Health, 169(1), 84–88. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2021-002015

Rhon, D. l I., Molloy, J. M., Monnier, A., Hando, B. R., & Newman, P. M. (2022). Much work remains to reach consensus on musculoskeletal injury risk in military service members: A systematic review with meta-analysis. European Journal of Sport Science, 22(1), 16–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.1931464

Rudzki, W., Delaney, T., & Macri, E. (2017). Military Personnel. In Brukner & Khan’s Clinical Sports Medicine: Injuries (5e ed., Vol. 1–1, pp. 991–1001). McGraw Hill. https://csm.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1970§ionid=168697060

Sammito, S., Hadzic, V., Karakolis, T., Kelly, K. R., Proctor, S. P., Stepens, A., White, G., & Zimmermann, W. O. (2021). Risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries in the military: A qualitative systematic review of the literature from the past two decades and a new prioritizing injury model. Military Medical Research, 8(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-021-00357-w

Smith, M. P., Klott, J., Hunter, P., & Klitzman, R. G. (2022). Multiligamentous Knee Injuries: Acute Management, Associated Injuries, and Anticipated Return to Activity. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 30(23), 1108–1115. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00830

Stannard, J., & Fortington, L. (2021). Musculoskeletal injury in military Special Operations Forces: A systematic review. BMJ Military Health, 167(4), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2020-001692

Tropf, J. G., Colantonio, D. F., Tucker, C. J., & Rhon, D. I. (2022). Epidemiology of Meniscus Injuries in the Military Health System and Predictive Factors for Arthroscopic Surgery. The Journal of Knee Surgery, 35(10), 1048–1055. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1744189

Veterans Affairs Canada (2023). Knee Anatomy. License for use purchased from https://www.123rf.com/photo_210711660_anatomy-of-the-human-knee-joint- structure-diagram-schematic-vector-illustration-medical-science.html

Wijnhoven, H. A. H., De Vet, H. C. W., & Picavet, H. S. J. (2006). Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders is systematically higher in women than in men. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 22(8), 717–724. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ajp.0000210912.95664.53

World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/