Entitlement Eligibility Guideline (EEG)

Date reviewed: 22 January 2025

Date created: April 2006

ICD-11 code: AB52

VAC medical code: 00646 Hearing loss

This publication is available upon request in alternate formats.

Full document – PDF Version

Definition

There are three general types of hearing loss (HL) based on the anatomical site at which the hearing loss occurs:

- Sensorineural HL (SNHL): loss of hearing due to a defect in the cochlea or the vestibulocochlear/acoustic (cranial nerve VIII) whereby nerve impulses from the cochlea to the brain are diminished.

- Conductive HL: loss of hearing due to defective sound conduction from the external auditory canal to the middle ear.

- Mixed HL: loss of hearing due to a combination of SNHL and conductive HL.

Note: For Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) entitlement purposes:

- At the time of application, the applicant must have a current chronic HL disability (refer to diagnostic definition in diagnostic standard below), for entitlement to be considered. “Chronic” means that the condition has existed for at least six months. Signs and symptoms are generally expected to persist despite medical attention, although they may wax and wane over the six-month period and thereafter.

- A diagnosis of HL is to be used, regardless of the type.

- Vertigo, HL, and/or tinnitus may present as part of the symptom complex of a diagnosed medical condition, or they may present as a primary stand-alone diagnosed medical condition. In those presenting with symptoms of vertigo, HL, and/or tinnitus, but with a known diagnosed cause (e.g. Meniere’s disease), these symptoms are included in entitlement and assessment of the medical condition. Prior to adjudicating the entitlement and assessment of vertigo, HL, and/or tinnitus, or a diagnosed medical condition that may cause these symptoms, a close review of previously entitled medical conditions with potentially overlapping symptoms is required.

Diagnostic standard

Diagnosis

A diagnosis from a qualified physician (ENT [ear, nose and throat]/otolaryngologist, neurologist, or family physician), nurse practitioner, or an audiologist is required.

Diagnostic definitions

The following diagnostic definitions are summarized in VAC policy hearing loss and tinnitus. For further details please refer to this policy.

Normal hearing:

- As based on widely accepted standards, the range of normal hearing is considered to be between 0 and 25 decibels (dB) at all frequencies between 250 and 8000 hertz (inclusively).

Hearing loss:

- For VAC purposes, hearing loss is a decibel loss greater than 25 dB at frequencies between 250 and 8000 Hz (inclusively), where the losses are not sufficient to meet VAC’s definition of hearing loss disability, as described below.

- Where it is determined that hearing loss was documented during service or at the time of discharge and/or service is reasonably found to be the initiating factor causing the current hearing loss disability, then entitlement to disability benefits may be granted.

In the case of normal hearing during service, any hearing loss that occurs after service is considered post-discharge in origin and is not considered related to service.

Note: At the time of publication of this EEG, the health-related expert opinion and scientific evidence indicates that any SNHL related to noise exposure does not progress after the noise exposure has stopped.

- In certain cases, such as claims made posthumously for World War II service or in exceptional medical circumstances, service or current audiograms may not be available for entitlement purposes. These situations are addressed in the hearing loss and tinnitus policy.

Hearing loss disability:

- For VAC purposes, a hearing loss disability exists when there is an audiogram indicating a total decibel sum hearing loss (DSHL) of 100 dB or greater at the frequencies of 500, 1000, 2000, and 3000 Hz in either ear, or 50 dB or more in both ears at 4000 Hz.

Diagnostic considerations

Audiograms should be completed by a clinical/licensed/certified/registered audiologist or physician and submitted to the Department for entitlement or assessment purposes. The standards for these audiograms are listed below. Audiograms submitted from other sources such as hearing instrument specialists (HIS), may be considered by VAC if they meet these standards, and are co-signed by an audiologist or physician:

- the hearing should be tested in both ears at 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, 6000 and 8000 Hz

- air and bone conduction values in both ears should be recorded

- speech reception thresholds (SRTs) for each ear should be recorded

- an indication of reliability of the audiogram should be indicated

- a narrative description of the test results may also be provided.

Audiograms that do not meet these standards should be considered by the decision maker on a case-by-case basis. The determination of reliability is based on the interpretation of information provided on the audiogram, the age of the audiogram (preferably completed within the last two years), and its consistency with previous audiograms.

When the measured threshold of hearing on an audiogram is decreased, this decrease may be temporary or permanent. The shift is referred to as either a temporary threshold shift (TTS) or a permanent threshold shift (PTS). Immediately after an exposure, there may be a TTS which can often be expected to recover over time. Only permanent HL is entitled, and this may require several audiograms to establish.

Auditory brain stem response testing may be used to confirm audiogram reliability.

Note: Older audiograms may use Acoustical Society of America (ASA) Standard values. To convert ASA hearing losses to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) or American National Standards Institute (ANSI) levels, refer to Appendix A: ASA to ISO-ANSI conversion.

Anatomy and physiology

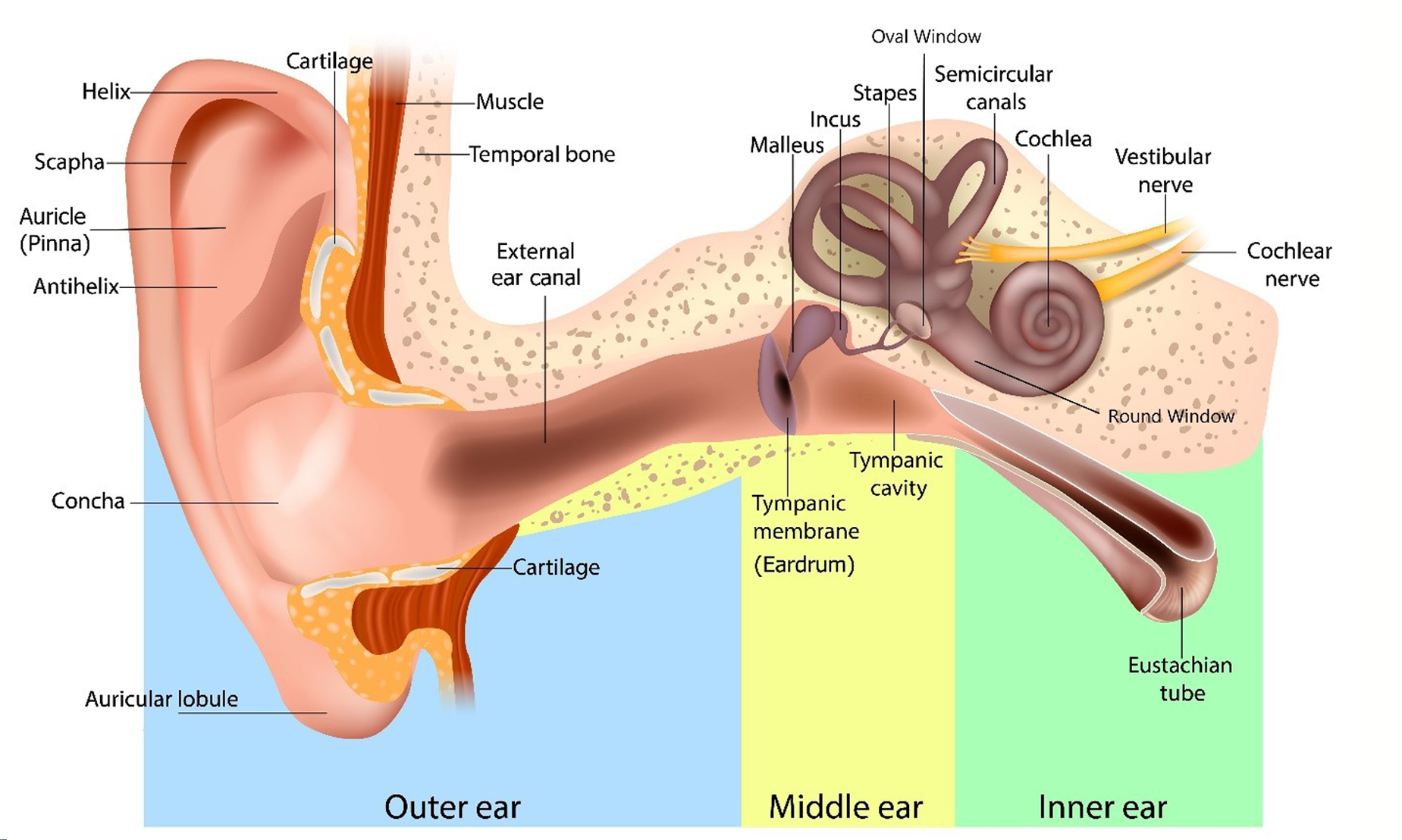

Hearing is the processing and interpretation of sound by the brain. The ear and vestibulocochlear nerve collect sound, convert it to electrical impulses, and then transmit those impulses to the brain. Pathology at any point along this pathway, from the auricle (pinna) to the brain, can result in HL.

Sounds are collected by the auricle and transmitted down the external ear canal to set the tympanic membrane (TM), or eardrum, in motion (Figure 1: Ear anatomy). The eardrum separates the canal from the middle ear with its three ossicles: the malleus, also known as hammer; the incus also known as anvil; and the stapes, also known as stirrup. The eardrum's vibrations are picked up and amplified by the ossicles and conducted to the cochlea. This whole system, from the auricle to the stapes, is the conducting apparatus of the ear.

Figure 1: Ear anatomy

The ossicle's vibrations are transmitted indirectly to the fluid in the cochlea. Movement of the fluid stimulates the cochlea's hair cells in the organ of Corti, resulting in electrical impulses that are transmitted along the vestibulocochlear nerve to the brain. This whole system, from the cochlea to the auditory cortex in the brain, is the sensorineural apparatus.

A complete audiogram shows hearing by both air conduction and bone conduction.

Types of hearing loss:

Conductive HL is the result of sound waves not being transmitted effectively to the inner ear because of some interference in the external canal, the ear drum, the ossicular chain, the middle ear cavity, the oval window, the round window, or the eustachian tube.

In pure conductive HL, there is no damage to the inner ear or the neural pathway. Any abnormality in the system, from wax in the ear canal to fixation of the stapes by otosclerosis, can cause a conductive HL.

On audiogram, hearing by air conduction is decreased and hearing by bone conduction is normal as it bypasses the above structures. The air conduction graph is therefore at a lower level in the audiogram than the bone conduction graph. The gap between the two graphs is known as the "air-bone gap.”

Sensorineural (SNHL) is the result of any abnormality in the structures of the sensorineural apparatus such as cochlear damage or vestibular schwannoma/acoustic neuroma.

On an audiogram, air and bone conduction are affected equally; the two graphs are at approximately the same level, and there is no “air-bone gap”.

- Mixed HL is when air and bone conduction are both affected, but the loss by air is more severe than the loss by bone. The air conduction graph is lower than the bone conduction graph. There is an “air-bone gap” on the audiogram.

Clinical features

Noise exposure:

Noise exposure is a common cause of HL. The mechanism by which excessive noise induces HL is by direct mechanical damage of cochlear hair cells in the organ of Corti. To cause damage to the ear that may result in HL, noise must be loud enough and of sufficient duration. The HL may be:

Temporary: a TTS with complete recovery of hearing in a few hours to a few weeks. This occurs when the hair cells in the organ of Corti are able to recover;

or

- Permanent: a PTS with permanent loss of hearing. This occurs when the hair cells in the organ of Corti are unable to recover.

There are two separate and distinct types of HL caused by excessive noise exposure:

- Noise induced HL which is associated with repeated or ongoing exposure to sound. The degree of HL, if any, is related to the level of sound and the length of exposure. Noise exposure that is a combination of loud enough and long enough causes damage to the hair cells of the organ of Corti which is extensive enough to prevent recovery, resulting in permanent HL.

- Acoustic trauma which is associated with a single episode of exposure to a hazardous level of noise. This may be either an impact noise which is associated by the collision of two objects or impulse noise which is the sudden release of energy from an explosion or weapon fire. The noise may be of sufficient intensity to permanently damage the hair cells of the organ of Corti. In the case of acoustic trauma arising from a blast injury, there may be also direct physical injury to the hearing apparatus, other than the hair cells of the organ of Corti, from the blast; this is called aural trauma due to noise.

There is a clear tendency for the ear to be more tolerant of noise at the low frequencies as opposed to the middle and higher frequencies. The ear is particularly vulnerable to frequencies in the range of 2000 to 4000 Hz, or even 6000 Hz. These frequencies are likely to be generated in industrial settings by various hammering, stamping, pressing, shipping and riveting operations, and in other settings by gunfire, explosions, and some types of aircraft noise.

The loudness level or intensity of noise (measured in dBs) and the length of exposure determine whether excessive noise exposure has occurred. Exceeding maximum exposure times may result in HL. Continued exposure to noise above 85 dB for more than 8 hours/day may cause HL and a single, intense exposure above 140 dB can cause immediate hearing damage. Risk of noise damage requires less time as the dB increase. The frequency of the noise exposure, measured in cycles per second or Hz, is also important information as high frequency noise can cause more damage than low-frequency noise. For example, Canadian Occupational Exposure Limits for Noise lists federally regulated employers by province.

Characteristically, the first sign of noise damage appears as a dip, or notch, at one of the higher frequencies, usually 4000 or 6000 Hz. The notching configuration is not, however, always present. For example, it may be obliterated by the effects of aging or continued exposure to noise.

With continued noise exposure, the HL becomes permanent because of irreparable damage to the cochlea's hair cells. As exposure continues, more hair cells are damaged and the HL, although remaining most severe in the upper frequencies, extends to the lower frequencies.

Above a certain intensity, noise becomes explosive and causes blast-type injuries.

- SNHL: the blast may tear the sensitive part of the cochlea (the organ of Corti) from its moorings, causing permanent and irreparable SNHL.

Conductive HL: the blast may rupture the eardrum, causing a conductive HL. If no further damage has been done, the HL may be temporary; if the eardrum heals, complete restoration to normal is possible. The blast may damage or dislocate the ossicles of the middle ear, causing a conductive HL that may be permanent unless the ear is successfully operated upon.

Note: Any combination of blast type injuries may occur, therefore the HL may be conductive, sensorineural, or mixed.

Age-related HL (presbycusis):

Age-related HL is a bilateral HL associated with advancing age. The most common pathology is of the sensory cells of the cochlea but can include conductive and central dysfunction. Age-related HL generally affects the high frequencies of hearing, with the audiogram showing a gradual downward slope with increasing frequency. As HL progresses, any evidence of a noise notch on audiogram is often lost.

Age-related HL affects more than half of adults by age 75 years, and nearly all adults who are 90 or older. It is more common in males than females.

Entitlement considerations

In this section

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

For Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) entitlement purposes, the following factors are accepted to cause or aggravate the conditions included in the Definition section of this EEG, and may be considered along with the evidence to assist in establishing a relationship to service. The factors have been determined based on a review of up-to-date scientific and medical literature, as well as evidence-based medical best practices. Factors other than those listed may be considered, however consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

The timelines cited below are for guidance purposes. Each case should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and its own merits.

Factors

Note: Unless indicated otherwise, the following factors may be associated with sensorineural, conductive, or mixed HL.

- Being above the age of 50 at the clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL. Age-related HL is the SNHL that occurs with increasing age. It occurs in over half of the population after age 75. For VAC entitlement purposes, age-related HL is considered to be multifactorial and includes HL due to significant noise exposure.

Exposure to intermittent or continuous exposure to noise, other than acoustic trauma, of sufficient intensity and duration to cause a DSHL of 100 dB or greater at frequencies of 500, 1000, 2000 and 3000 Hz in either ear, or 50 dB or more in both ears at 4000 Hz, during or just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL.

Consideration may be given to variables including, but not limited to, the following:

- level of the noise hazard*

- continuity of noise hazard (intermittent or continuous)*

- duration of noise hazard*

- presence or absence of adequate ear protection

- location of noise hazard (e.g. in enclosed or open area).

Note: *refer to noise exposure section above.

Exposure to at least one episode of acoustic trauma just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL. The following exposures may result in acoustic trauma:

- fireworks

- loud music

- heavy machinery

- gunfire

- blast injury (i.e. exploding grenades, mines or bombs).

Acoustic trauma is caused by short-term intense exposure to loud noise resulting in sudden damage to the hair cells of the organ of Corti, usually producing immediate symptoms of SNHL, pain (especially with loud noises) or tinnitus in the affected ear(s). The immediate symptoms, including sensorineural deafness, may abate over a few days. HL present at eight weeks post exposure is likely to be permanent.

- Exposure to at least one episode of aural trauma caused by noise just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of sensorineural, conductive or mixed HL. Aural trauma caused by noise is caused by exposure to a blast resulting in sudden physical damage to any portion of the middle or inner ear. Aural trauma to noise may result in the following conditions:

- Permanent damage to the TM resulting in conductive HL.

- Damage to the ossicles resulting in conductive HL.

- Damage to the organ of Corti resulting in immediate symptoms of SNHL, pain, or tinnitus in the affected ear(s). The immediate symptoms, including sensorineural deafness, may abate over a few days. HL present at eight weeks post exposure is likely to be permanent.

Sustaining damage to the middle ear from inequalities in the barometric pressure (other than due to noise) on each side of the TM, known as otic barotrauma, within approximately 30 days prior to clinical onset or aggravation of HL. The type of HL depends on the site of injury.

Ear barotrauma can occur when there is a difference in the air pressure between the middle ear and the external environment. It can present with ear pressure, pain, tinnitus and HL. Ear barotrauma is generally associated with eustachian tube dysfunction. Normally the air in the middle ear is absorbed into the mucosal lining and is continually replaced via the eustachian tube.

When the eustachian tube is blocked, the pressure in the middle ear decreases and the TM is retracted. The stretching of the TM can lead to bleeding or bruising in the TM, fluid in the middle ear, and occasionally TM rupture. Injuries to the TM and middle ear may lead to a conductive HL.

Less severe injuries, including most TM rupture, generally heal with time. More severe injuries can involve the structures of the middle ear. SNHL is a rare complication following otic barotrauma and is usually associated with a peri lymphatic fistula (PLF). PLF’s occur when the thin membrane at either the oval or round windows are disturbed by trauma resulting in a leak of fluid from the labyrinth into the middle ear, commonly causing symptoms of vertigo and tinnitus.

The following exposures may result in ear barotrauma:

- flying

- sky diving

- underwater diving

- working in a submarine

- being treated in a hyperbaric or hypobaric oxygen chamber

- slap to the outer ear.

- Having idiopathic sudden SNHL (SSNHL) at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL. This type of HL is characterized by SNHL of at least 30 dB over the course of 72 hours. There are identifiable causes of SSNHL such as post viral, autoimmune disease, medications, vascular disorders and trauma, which are not included under idiopathic.

- Having chronic otitis externa with obstruction of the external auditory canal on the affected side just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL. Malignant otitis externa is one example of a chronic otitis externa which could produce a permanent conductive HL.

- Having chronic otitis media on the affected side just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL. Chronic otitis media may result in any of the following:

- perforation of TM (if small, the perforation generally heals spontaneously)

- medial meatal fibrosis

- erosion of ossicles and TM.

- Having acute suppurative otitis media on the affected side just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL. The main complaint is pain. There is pus accumulation in the middle ear and bulging of the eardrum. If the ear drum ruptures, a conductive HL is present immediately. With proper treatment, hearing usually returns completely to normal. With or without treatment, the perforation may persist. Hearing may or may not return to normal, depending on the size and location of the perforation.

- Having nonsuppurative otitis media on the affected side just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL. The middle ear in this variety contains serous or mucoid fluid. There is a conductive HL which can be reversed by treatment, however, if left untreated the condition may progress to chronic adhesive otitis media, i.e. scarring of the middle ear, with a permanent conductive HL. Also known as "catarrhal otitis media,” "serous otitis media,” "otitis media with effusion" and other names.

- Having suppurative labyrinthitis of the affected ear within approximately 30 days prior to clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL. Suppurative labyrinthitis means inflammation of the labyrinth, a system of interconnecting canals in the inner ear, characterized by the formation of pus.

- Having a penetrating injury to the middle ear on the affected side within approximately seven days prior to clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL. The injury is caused by the intrusion of a foreign body such as a weapon, implement, stick, bullet or shrapnel fragment into the tympanic cavity.

- Having a permanent obstruction of the external auditory canal on the affected side at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL.

- Having an invasive granuloma causing obstruction of the external auditory canal on the affected side at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL. Examples include a granulomatous foreign body, tuberculous and sarcoid granulomata.

Having a benign or malignant neoplasm affecting the auditory apparatus on the affected side prior to clinical onset or aggravation of HL. A benign or malignant neoplasm means a primary or secondary neoplasm of the auditory nerve, inner ear, temporal bone, cerebellopontine angle or posterior cranial fossa (i.e. the part of the skull lodging the hindbrain) which includes the cerebellum, pons, and the medulla oblongata.

Neoplasm: A primary or secondary neoplasm (tumour) invading the middle ear or causing at least 90% obstruction of the external auditory canal on the affected side at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL. It produces conductive HL by interfering with the motion mechanics of the middle ear and ossicles, or by obstruction of the auditory canal.

Tumours may involve the middle ear, mastoid, and the temporal bone primarily.

Using medication from the specified list of medications below during or just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL. The medications include, but are not limited to, the following:

- a parenteral aminoglycoside antibiotic:

- gentamicin

- streptomycin

- kanamycin

- amikacin

- netilmicin

- tobramycin.

- intravenous administration of:

- ethacrynic acid

- bumetanide

- vancomycin

- erythromycin.

- chemotherapeutic agents:

- nitrogen mustard

- bleomycin

- cisplatin

- a-difluoromethylornithine

- vincristine

- vinblastine

- misonidazole

- 6-amino nicotinamide

- carboplatin.

- salicylate or quinine derivatives at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of HL is generally reversible after cessation of these medications.

Note:

- Individual medications may belong to a class of medications. The effects of a specific medication may vary from the class. The effects of the specific medication should be considered.

- If it is claimed a medication resulted in the clinical onset or aggravation of HL the following must be established:

- The medication was prescribed to treat an entitled condition.

- The individual was receiving the medication at the time of the clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL.

- The current medical literature supports the medication can result in the clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL.

- The medication use is long-term, ongoing, and cannot reasonably be replaced with another medication or the medication is known to have enduring effects after discontinuation.

- a parenteral aminoglycoside antibiotic:

Having Meniere’s disease at time of clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL.

Note: Where entitlement is granted for Meniere’s disease, HL is included in an entitlement and assessment of this condition.

- Having a systemic immune mediated disorder at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL. These include:

- Wegener's granulomatosis

- Cogan syndrome

- Behçet's syndrome

- rheumatoid arthritis (refer below)

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- periarteritis nodosa.

- Having rheumatoid arthritis involving any synovial joint of the head and neck prior to clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL. The joints between the incudomalleolar and incudostapedial joints are synovial and thus in rare instances may develop rheumatoid arthritis.

- Having leprosy of the structures of the hearing apparatus just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of sensorineural, conductive or mixed HL. Leprosy is a slowly progressive chronic infectious disease caused by mycobacterium leprae primarily affecting the skin and peripheral nerves, including peripheral sensory nerves.

- Having an acute vascular lesion involving the arteries supplying the cochlea on the affected side at time of clinical onset or aggravation SNHL.

- Having hyperviscosity syndrome within approximately 30 days prior to clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL. This includes:

- Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia

- polycythemia

- the leukemias

- multiple myeloma

- sickle cell trait.

- Having an acute infection from a virus listed below within approximately 30 days prior to clinical onset or aggravation of sensorineural hearing loss. This is generally sudden sensorineural hearing loss, with hearing loss developing rapidly in less than 72 hours. The viruses include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Lassa virus

- mumps virus

- measles virus

- pertussis virus

- varicella-zoster virus.

- Having bacterial meningitis within weeks or months prior to clinical onset or aggravation of sensorineural hearing loss. Bacterial meningitis is an inflammation of the lining of the brain and spinal cord caused by bacteria. Common types include:

- Hemophilus influenzae meningitis

- meningococcal meningitis

- pneumococcal meningitis

- tuberculous meningitis.

- Having neurosyphilis prior to clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL. Central nervous system manifestations of syphilis, which is a sub-acute chronic infectious disease caused by the spirochaete treponema pallidum, characterized by episodes of active disease interrupted by periods of latency. HL should develop during an active phase of the illness.

- Having tuberculosis involving the temporal bone on the affected side of the head prior to clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL.

- Having Paget’s disease of bone affecting the skull at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of sensorineural, conductive or mixed HL. Also known as osteitis deformans, it is a disease of bone marked by repeated episodes of bone resorption and new bone formation resulting in weakened deformed bones of increased mass.

- Having otosclerosis at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL. Otosclerosis is a primary disorder of the labyrinthine capsule characterized by new bone formation and often involving the footplate of the stapes.

Having a moderate or severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) at the time of onset or aggravation of SNHL. It is important for timelines to be established.

Note: If considering entitlement for HL due to a mild TBI, consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

- Having a head injury with temporal bone fracture within a few weeks of clinical onset or aggravation of HL. Transverse fractures of the temporal bone may cause injury to the cochleovestibular nerve resulting in a SNHL. Fractures of the temporal bone may also result in conductive HL because of ossicular chain injuries.

Having a course of therapeutic radiation which includes the cochlea or vestibulocochlear/acoustic nerve prior to clinical onset or aggravation of SNHL.

Therapeutic radiation where the temporal bone of the affected side was in the radiation field prior to clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL. Osteoradionecrosis of the temporal bone may produce chronic infection which may result in conductive HL.

Therapeutic radiation may cause conductive hearing impairment due to dryness and scaling of the skin of the external auditory canal, leading to build up of debris or through eustachian tube dysfunction with secretory otitis media. These generally resolve after the radiation is complete.

- Having a cholesteatoma, a cyst like growth originating in the middle ear, in the affected ear at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of HL. Cholesteatomas may develop consequential to chronic otitis media or perforation of the tympanic membrane. They tend to grow and expand into surrounding bone and into the mastoid cavity.

- Having a cleft palate at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of conductive HL.

- Inability to obtain appropriate clinical management of sensorineural, conductive or mixed HL.

Note: At the time of publication of this EEG, the health-related expert opinion and scientific evidence indicates that any SNHL related to noise exposure does not progress after the noise exposure has stopped.

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment

Section B provides a list of diagnosed medical conditions which are considered for VAC purposes to be included in the entitlement and assessment of HL.

- Hearing loss of all types in an entitled ear, whether of sensorineural, conductive or mixed types. This includes:

- Age-related HL/Presbycusis

Section C: Common medical conditions which may result, in whole or in part, from hearing loss and/or its treatment

Section C is a list of conditions which can be caused or aggravated by HL and/or its treatment. Conditions listed in Section C are not included in the entitlement and assessment of HL. A consequential entitlement decision may be considered where the individual merits and the medical evidence of the case supports a consequential relationship.

Conditions other than those listed in Section C may be considered; consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

- Otitis externa from the wearing of hearing aids

- Tinnitus

Note:

- At the time of publication of this EEG, the health-related expert opinion and scientific evidence is insufficient to support that HL causes or aggravates dementia.

- The entitlement and disability assessment of HL includes the communication difficulties that may be experienced by individuals with HL. For VAC entitlement purposes, such communication difficulties are not considered to cause a permanent aggravation of dementia.

- HL does not cause or permanently aggravate Meniere’s disease. HL is included in the entitlement of Meniere’s disease.

Appendix A: ASA to ISO-ANSI conversion

It is important to note the literature indicates American audiometric data collected prior to 1969/1970 may be based on the ASA standard. As late as 1977 it was recommended audiogram blanks be labelled as ISO or ANSI to ensure all hearing levels in a report were actually ANSI or ISO (Hearing and Deafness, 4th ed., p. 287).

Links

Related VAC guidance and policy:

- Chronic Otitis Media – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Meniere’s Disease – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Otosclerosis - Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Paget's Disease of Bone (Osteitis Deformans) - Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Rheumatoid Arthritis – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Tinnitus - Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Traumatic Brain Injury – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Vertiginous Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Hearing Loss and Tinnitus - Policies

- Pain and Suffering Compensation – Policies

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police Disability Pension Claims – Policies

- Dual Entitlement – Disability Benefits – Policies

- Establishing the Existence of a Disability – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Peacetime Military Service – The Compensation Principle – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Wartime and Special Duty Service – The Insurance Principle – Policies

- Disability Resulting from a Non-Service Related Injury or Disease – Policies

- Consequential Disability – Policies

- Benefit of Doubt – Policies

References as of 22 January 2025

Amieva, H., Ouvrard, C., Meillon, C., Rullier, L., & Dartigues, J.-F. (2018). Death, Depression, Disability, and Dementia Associated With Self-reported Hearing Problems: A 25-Year Study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 73(10), 1383–1389. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx250

Andries, E., Bosmans, J., Engelborghs, S., Cras, P., Vanderveken, O. M., Lammers, M. J. W., Van de Heyning, P. H., Van Rompaey, V., & Mertens, G. (2023). Evaluation of Cognitive Functioning Before and After Cochlear Implantation in Adults Aged 55 Years and Older at Risk for Mild Cognitive Impairment. JAMA Otolaryngology-- Head & Neck Surgery, 149(4), 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2022.5046

Armstrong, N. M., An, Y., Doshi, J., Erus, G., Ferrucci, L., Davatzikos, C., Deal, J. A., Lin, F. R., & Resnick, S. M. (2019). Association of Midlife Hearing Impairment With Late-Life Temporal Lobe Volume Loss. JAMA Otolaryngology-- Head & Neck Surgery, 145(9), 794–802. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1610

Aronson, J. K. (Ed.). (2015). Meyler’s side effects of drugs: The international encyclopedia of adverse drug reactions and interactions (16. Ed). Elsevier.

Arts, H., & Adams, M. (2020). Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Adults in Cummings Otolarungology: Head and Neck Surgery. In Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (1996). Statement of Principles concerning conductive hearing loss (Balance of Probabilities) (No. 20 of 1996). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (1996). Statement of Principles concerning conductive hearing loss (Reasonable Hypothesis) (No. 19 of 1996). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2001). Statement of Principles concerning sensorineural hearing loss (Balance of Probabilities) (No. 30 of 2001). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2001). Statement of Principles concerning sensorineural hearing loss (Reasonable Hypothesis) (No. 29 of 2001). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2019). Statement of Principles concerning conductive hearing loss (Balance of Probabilities) (No. 82 of 2019). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2019). Statement of Principles concerning conductive hearing loss (Reasonable Hypothesis) (No. 81 of 2019). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2019). Statement of Principles concerning sensorineural hearing loss (Balance of Probabilities) (No. 99 of 2019). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2019). Statement of Principles concerning sensorineural hearing loss (Reasonable Hypothesis) (No. 98 of 2019). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Bergemalm, P.-O., & Lyxell, B. (2005). Appearances are deceptive? Long-term cognitive and central auditory sequelae from closed head injury. International Journal of Audiology, 44(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020400022546

Blevins, N. (2022). Presbycusis. UpToDate, Inc. https://www.dynamed.com/condition/presbycusis

Bohne, B. A., Kimlinger, M., & Harding, G. W. (2017). Time course of organ of Corti degeneration after noise exposure. Hearing Research, 344, 158–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2016.11.009

Chen, J. X., Lindeborg, M., Herman, S. D., Ishai, R., Knoll, R. M., Remenschneider, A., Jung, D. H., & Kozin, E. D. (2018). Systematic review of hearing loss after traumatic brain injury without associated temporal bone fracture. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 39(3), 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2018.01.018

Chern, A., & Golub, J. S. (2019). Age-related Hearing Loss and Dementia. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 33(3), 285–290. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0000000000000325

Dalgıç, A., Yılmaz, O., Hıdır, Y., Satar, B., & Gerek, M. (2015). Analysis of Vestibular

Evoked Myogenic Potentials and Electrocochleography in Noise Induced Hearing Loss. The Journal of International Advanced Otology, 11(2), 127–132. https://doi.org/10.5152/iao.2015.1025

Davis, H., & Silverman, S. R. (Eds.). (1978). Hearing and Deafness (4th edition). Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Dawes, P., & Völter, C. (2023). Do hearing loss interventions prevent dementia? Zeitschrift Fur Gerontologie Und Geriatrie, 56(4), 261–268.

Deal, J. A., Betz, J., Yaffe, K., Harris, T., Purchase-Helzner, E., Satterfield, S., Pratt, S., Govil, N., Simonsick, E. M., Lin, F. R., & Health ABC Study Group. (2017). Hearing Impairment and Incident Dementia and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: The Health ABC Study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 72(5), 703–709. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw069

Department of Veterans Affairs, Canada (1997). A Review of Noise Induced Hearing Loss, Tinnitus and Evoked Response Audiometry.

Esquivel, C. R., Parker, M., Curtis, K., Merkley, A., Littlefield, P., Conley, G., Wise, S., Feldt, B., Henselman, L., & Stockinger, Z. (2018). Aural Blast Injury/Acoustic Trauma and Hearing Loss. Military Medicine, 183(suppl_2), 78–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy167

Fauci, A., Braunwald, E., Isselbacher, K., Wilson, J., Martin, J., Kasper, D., Hauser, S., & Longo, D. (1998). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 14th Edition. 36(9), 665–665. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3100671

Ferrite, S., Santana, V. S., & Marshall, S. W. (2011). Validity of self-reported hearing loss in adults: Performance of three single questions. Revista De Saude Publica, 45(5), 824–830. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-89102011005000050

Flint, P. W., Haughey, B. H., Lund, V. J., Robbins, K. T., Thomas, J. R., Lesperance, M. M.,& Francis, H. W. (2020). Cummings Otolaryngology E-Book: Head and Neck Surgery, 3-Volume Set. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Gates, G. A., Schmid, P., Kujawa, S. G., Nam, B., & D’Agostino, R. (2000). Longitudinal threshold changes in older men with audiometric notches. Hearing Research, 141(1–2), 220–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-5955(99)00223-3

Guest, H., Munro, K. J., Prendergast, G., Howe, S., & Plack, C. J. (2017). Tinnitus with a normal audiogram: Relation to noise exposure but no evidence for cochlear synaptopathy. Hearing Research, 344, 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2016.12.002

Hafdi, M., Hoevenaar-Blom, M. P., & Richard, E. (2021). Multi-domain interventions for the prevention of dementia and cognitive decline. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11(11), CD013572. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013572.pub2

Hammill, T. L., & Campbell, K. C. (2018). Protection for medication-induced hearing loss: The state of the science. International Journal of Audiology, 57(sup4), S87–S95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2018.1455114

Hanna, B. (2024). Vestibula Neuritis. In DynaMed. EBSCO Information Services. https://www.dynamed.com/condition/vestibular-neuritis/about

Helfer, T. M., Jordan, N. N., Lee, R. B., Pietrusiak, P., Cave, K., & Schairer, K. (2011). Noise-induced hearing injury and comorbidities among postdeployment U.S. Army soldiers: April 2003-June 2009. American Journal of Audiology, 20(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1044/1059-0889(2011/10-0033)

Hirsch, M., & Birnbaum, R. (2023). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Pharmacology, administration, and side effects. UpToDate, Inc.

Jafari, Z., Kolb, B. E., & Mohajerani, M. H. (2022). Hearing Loss, Tinnitus, and Dizziness in COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques, 49(2), 184–195. https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2021.63

Jiang, F., Mishra, S. R., Shrestha, N., Ozaki, A., Virani, S. S., Bright, T., Kuper, H., Zhou, C., & Zhu, D. (2023). RETRACTED - Association between hearing aid use and all-cause and cause-specific dementia: An analysis of the UK Biobank cohort. The Lancet. Public Health, 8(5), e329–e338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00048-8

Karch, S. J., Capó-Aponte, J. E., McIlwain, D. S., Lo, M., Krishnamurti, S., Staton, R. N., & Jorgensen-Wagers, K. (2016). Hearing Loss and Tinnitus in Military Personnel with Deployment-Related Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. U.S. Army Medical Department Journal, 3–16, 52–63.

Kliegman, R. M., & Geme, J. W. S. (2019). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Kuhn, M., Heman-Ackah, S. E., Shaikh, J. A., & Roehm, P. C. (2011). Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Review of Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis. Trends in Amplification, 15(3), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084713811408349

Kujawa, S. G., & Liberman, M. C. (2006). Acceleration of Age-Related Hearing Loss by Early Noise Exposure: Evidence of a Misspent Youth. The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(7), 2115–2123. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4985-05.2006

Kurabi, A., Keithley, E. M., Housley, G. D., Ryan, A. F., & Wong, A. C.-Y. (2017). Cellular mechanisms of noise-induced hearing loss. Hearing Research, 349, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2016.11.013

Lang, E. (2023). Dizziness in Adults—Approach to the Patient. In DynaMed. EBSCO Information Services.

Liberman, M. C., & Kujawa, S. G. (2017). Cochlear synaptopathy in acquired sensorineural hearing loss: Manifestations and mechanisms. Hearing Research, 349, 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2017.01.003

Lie, A., Skogstad, M., Johannessen, H. A., Tynes, T., Mehlum, I. S., Nordby, K.-C., Engdahl, B., & Tambs, K. (2016). Occupational noise exposure and hearing: A systematic review. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 89(3), 351–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-015-1083-5

Lin, F. R., Metter, E. J., O’Brien, R. J., Resnick, S. M., Zonderman, A. B., & Ferrucci, L. (2011). Hearing loss and incident dementia. Archives of Neurology, 68(2), 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2010.362

Lisko, I., Kulmala, J., Annetorp, M., Ngandu, T., Mangialasche, F., & Kivipelto, M. (2021). How can dementia and disability be prevented in older adults: Where are we today and where are we going? Journal of Internal Medicine, 289(6), 807–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13227

Liu, X., & Yan, D. (2007). Ageing and hearing loss. The Journal of Pathology, 211(2), 188–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.2102

Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Brayne, C., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Cooper, C., Costafreda, S. G., Dias, A., Fox, N., Gitlin, L. N., Howard, R., Kales, H. C., Kivimäki, M., Larson, E. B., Ogunniyi, A., … Mukadam, N. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet (London, England), 396(10248), 413–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

Livingston, G., Sommerlad, A., Orgeta, V., Costafreda, S. G., Huntley, J., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Cooper, C., Fox, N., Gitlin, L. N., Howard, R., Kales, H. C., Larson, E. B., Ritchie, K., Rockwood, K., Sampson, E. L., … Mukadam, N. (2017). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet (London, England), 390(10113), 2673–2734. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6

Loughrey, D. G., Kelly, M. E., Kelley, G. A., Brennan, S., & Lawlor, B. A. (2018). Association of Age-Related Hearing Loss With Cognitive Function, Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, 144(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2513

Loughrey, D. G., Kelly, M. E., Kelley, G. A., Brennan, S., & Lawlor, B. A. (2018). Association of Age-Related Hearing Loss With Cognitive Function, Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngology-- Head & Neck Surgery, 144(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2513

Lustig, L., Limb, C., & Durand, M. (2023). Chronic Otitis Media and Cholesteatoma in Adults. UpToDate, Inc.

Marinelli, J. P., Lohse, C. M., Fussell, W. L., Petersen, R. C., Reed, N. S., Machulda, M. M., Vassilaki, M., & Carlson, M. L. (2022). Association between hearing loss and development of dementia using formal behavioural audiometric testing within the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA): A prospective population-based study. The Lancet. Healthy Longevity, 3(12), e817–e824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00241-0

Moore, B. C. J. (2021). The Effect of Exposure to Noise during Military Service on the Subsequent Progression of Hearing Loss. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052436

Mosnier, I., Bebear, J.-P., Marx, M., Fraysse, B., Truy, E., Lina-Granade, G., Mondain, M., Sterkers-Artières, F., Bordure, P., Robier, A., Godey, B., Meyer, B., Frachet, B., Poncet-Wallet, C., Bouccara, D., & Sterkers, O. (2015). Improvement of cognitive function after cochlear implantation in elderly patients. JAMA Otolaryngology-- Head & Neck Surgery, 141(5), 442–450. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2015.129

Muhr, P., Månsson, B., & Hellström, P. A. (2006). A study of hearing changes among military conscripts in the Swedish Army: Estudio de los cambios auditivos en conscriptos de la Armada Sueca. International Journal of Audiology, 45(4), 247–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020500190052

Nadhimi, Y., & Llano, D. A. (2021). Does hearing loss lead to dementia? A review of the literature. Hearing Research, 402, 108038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2020.108038

Natarajan, N., Batts, S., & Stankovic, K. M. (2023). Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(6), 2347. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062347

Newby, H. A., & Popelka, G. R. (1992). Audiology (6th ed). Prentice Hall; WorldCat.

Nolan, L. S. (2020). Age‐related hearing loss: Why we need to think about sex as a biological variable. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 98(9), 1705–1720. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24647

Paparella, M. M., da Costa, S. S., & Fagan, J. (1991). Paparella’s Otolaryngology: Head & Neck Surgery: Two Volume Set (3rd ed). Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers.

Pichora-Fuller, M. K., Schneider, B. A., & Daneman, M. (1995). How young and old adults listen to and remember speech in noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97(1), 593–608. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.412282

Powell, D. S., Oh, E. S., Reed, N. S., Lin, F. R., & Deal, J. A. (2021). Hearing Loss and Cognition: What We Know and Where We Need to Go. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 13, 769405. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.769405

Priya, J. S., & Hohman, M. H. (2024). Noise Exposure and Hearing Loss. In StatPearls.

StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594247/

Rosdina, A., Leelavathi, M., Zaitun, A., Lee, V., Azimah, M., Majmin, S., & Mohd, K. (2010). Self-reported hearing loss among elderly malaysians. Malaysian Family Physician: The Official Journal of the Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia, 5(2), 91–94.

Rosenhall, U. (2015). Epidemiology of age-related hearing loss. Hearing, Balance and Communication, 13(2), 46–50. https://doi.org/10.3109/21695717.2015.1013775

Segal, S., Eviatar, E., Berenholz, L., Kessler, A., & Shlamkovitch, N. (2003a). Is There a Relation Between Acoustic Trauma or Noise-Induced Hearing Loss and a Subsequent Appearance of Ménière’s Disease?: An Epidemiologic Study of 17,245 Cases and a Review of the Literature: Otology & Neurotology, 24(3), 387391. https://doi.org/10.1097/00129492-200305000-00007

Senior, S. L. (2019). Health needs of ex-military personnel in the UK: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 165(6), 410–415. https://doi.org/10.1136/jramc-2018-001101

Sonstrom Malowski, K., Gollihugh, L. H., Malyuk, H., & Le Prell, C. G. (2022). Auditory changes following firearm noise exposure, a review. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 151(3), 1769–1791. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0009675

Swords, G. M., Nguyen, L. T., Mudar, R. A., & Llano, D. A. (2018). Auditory system dysfunction in Alzheimer disease and its prodromal states: A review. Ageing Research Reviews, 44, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2018.04.001

Talmi, Y. P., Finkelstein, Y., & Zohar, Y. (1991). Barotrauma-Induced Hearing Loss. Scandinavian Audiology, 20(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/01050399109070783

Tang, D., Tran, Y., Dawes, P., & Gopinath, B. (2023). A Narrative Review of Lifestyle Risk Factors and the Role of Oxidative Stress in Age-Related Hearing Loss. Antioxidants, 12(4), 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12040878

Tang, D., Tran, Y., Dawes, P., & Gopinath, B. (2023). A Narrative Review of Lifestyle Risk Factors and the Role of Oxidative Stress in Age-Related Hearing Loss. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 12(4), 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12040878

Thomson, R. S., Auduong, P., Miller, A. T., & Gurgel, R. K. (2017). Hearing loss as a risk factor for dementia: A systematic review. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology, 2(2), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.65

Tun, P. A., McCoy, S., & Wingfield, A. (2009). Aging, hearing acuity, and the attentional costs of effortful listening. Psychology and Aging, 24(3), 761–766. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014802

United States Department of Labor. (2014). Occupational Noise Exposure - Overview Occupational Safety and Health Administration. https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/noisehearingconservation/index.html

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Ear Anatomy [Image]. License purchased for use from Human Ear Anatomy. Ear Structure Diagram. The Human Ear Consists Of The Outer, Middle And Inner Ear. Royalty Free SVG, Cliparts, Vectors, and Stock Illustration. Image 180301021. (123rf.com)

Völter, C., Götze, L., Dazert, S., Falkenstein, M., & Thomas, J. P. (2018). Can cochlear implantation improve neurocognition in the aging population? Clinical Interventions in Aging, 13, 701–712. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S160517

Völter, C., Götze, L., Haubitz, I., Müther, J., Dazert, S., & Thomas, J. P. (2021). Impact of Cochlear Implantation on Neurocognitive Subdomains in Adult Cochlear Implant Recipients. Audiology & Neuro-Otology, 26(4), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1159/000510855

Waddell, K., DeMario, P., Dass, R., Grewak, E., Alam, S., & Wilson, M. (2024). Rapid evidence profile #76: Examining the association between hearing loss and dementia. Hamilton: McMaster Health Forum. https://www.mcmasterforum.org/about-us/products

Waddell K, Wu N, Demaio P, Bain T, Bhuiya A, Wilson MG. Rapid evidence profile #71: Examining the association between noise exposure and hearing loss. Hamilton: McMaster Health Forum. 10 May 2024. Examining the association between noise exposure and delayed hearing loss (mcmasterforum.org)

Weber, P. (2023). Sudden sensorineural hearing loss in adults: Evaluation and Management. UpToDate, Inc.

World Health Organization. (2022). ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision). https://icd.who.int/en

Yankaskas, K. (2013). Prelude: Noise-induced tinnitus and hearing loss in the military. Hearing Research, 295, 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2012.04.016

Yong, J., & Wang, D.-Y. (2015). Impact of noise on hearing in the military. Military Medical Research, 2(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-015-0034-5

Zanon, A., Sorrentino, F., Franz, L., & Brotto, D. (2019). Gender-related hearing, balance and speech disorders: A review. Hearing, Balance and Communication, 17(3), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/21695717.2019.1615812