Entitlement Eligibility Guideline (EEG)

Date reviewed: 27 August 2025

Date created: February 2005

ICD-11 code: MC41

VAC medical code: 38830 Tinnitus

This publication is available upon request in alternate formats.

Full document – PDF Version

Definition

Tinnitus is defined as the perception of a sound in one or both ears, or in the head, when it does not arise from an acoustic stimulus in the external environment.

For Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) purposes, vertigo, hearing loss (HL), and/or tinnitus may present as part of the symptom complex of a diagnosed medical condition, or they may present as a primary stand-alone diagnosed medical condition. In those presenting with symptoms of vertigo, HL, and/or tinnitus, but with a known diagnosed cause (e.g. Meniere’s disease), these symptoms are included in entitlement and assessment of the medical condition. Prior to adjudicating the entitlement and assessment of vertigo, HL, and/or tinnitus, or a diagnosed medical condition that may cause these symptoms, a close review of previously entitled medical conditions with potentially overlapping symptoms is required.

Note: Entitlement should be granted for a chronic condition only. For VAC purposes, "chronic" means that the condition has existed for at least six months. Signs and symptoms are generally expected to persist despite medical attention, although they may wax and wane over the six month period and thereafter.

Diagnostic standard

Diagnosis

A diagnosis from a qualified physician (ear, nose and throat [ENT] specialist/otolaryngologist, neurologist, or family physician), nurse practitioner, or an audiologist is required.

In the case of objective and/or unilateral tinnitus, a diagnosis from a physician, as listed above, is required.

Chronic tinnitus is of at least six months duration. A single indication or complaint of tinnitus is not sufficient for diagnostic purposes.

Hyperacusis is an increased sensitivity to sound resulting in everyday sounds being perceived as intense, unpleasant, and/or overwhelmingly loud. Hyperacusis and tinnitus are often present at the same time. For VAC entitlement purposes, entitlement for tinnitus includes hyperacusis.

Diagnostic considerations

An audiogram is required along with a clinical diagnosis. The cause of the tinnitus cannot be determined from an audiogram alone.

It is preferred that audiograms submitted to VAC for entitlement or assessment purposes be performed by a clinical/licensed/certified/registered audiologist or physician. The standards for these audiograms are listed below. Audiograms submitted from other sources such as hearing instrument specialists (HIS), may be considered by VAC if they meet these standards, and are co-signed by an audiologist or physician:

- the hearing should be tested in both ears at 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, 6000 and 8000 Hz

- air and bone conduction values in both ears should be recorded

- speech reception thresholds (SRTs) for each ear should be recorded

- an indication of reliability of the audiogram should be indicated

- narrative description of the test results may also be provided.

Audiograms that do not meet the above standards may be considered by the adjudicator on a case-by-case basis. The determination of reliability is based on the interpretation of information provided on the audiogram, the age of the audiogram, and its consistency with previous audiograms.

When the measured threshold of hearing on an audiogram is decreased, this decrease may be temporary or permanent. The shift is referred to as either a temporary threshold shift (TTS), or a permanent threshold shift (PTS). Immediately after an exposure, there may be a TTS which can often be expected to recover over time.

Note:

- Older audiograms may use Acoustical Society of America (ASA) Standard values. To convert ASA hearing losses to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) or American National Standards Institute (ANSI) levels, refer to Appendix A: ASA to ISO-ANSI conversion.

- If an audiogram is unavailable, refer to the hearing loss and tinnitus policy for instructions.

Anatomy and physiology

There are two types of tinnitus: subjective tinnitus and objective tinnitus.

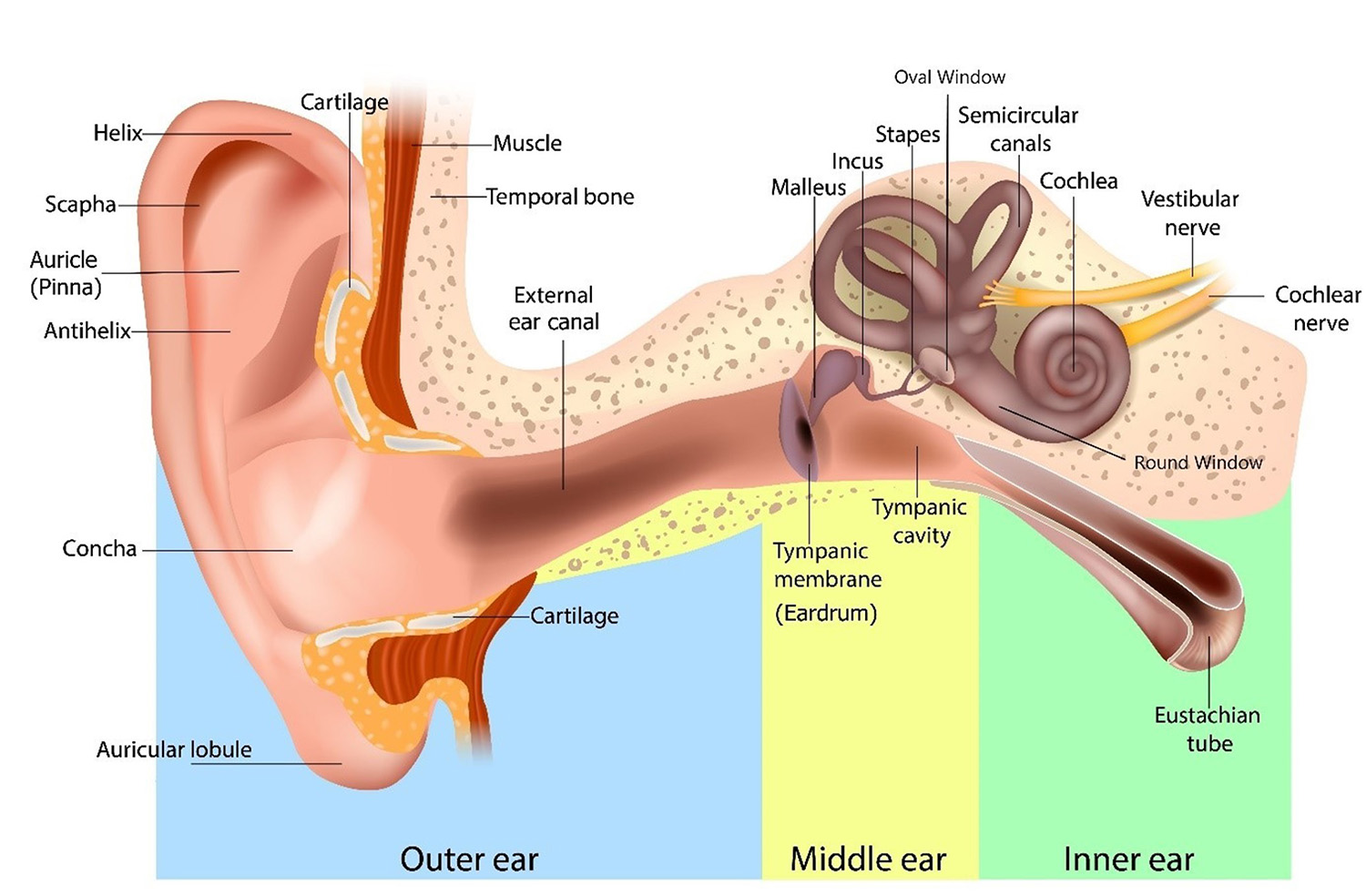

Subjective tinnitus is perceived by the individual only, and cannot be heard by anyone else. The mechanism and pathophysiology of this type of tinnitus remains obscure and is likely multifactorial, occurring at any point along the auditory pathway (Figure 1: Ear anatomy). This is by far the most common type of tinnitus and is the type associated with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL).

Objective tinnitus is not only heard by the individual, but may also be heard by others. The quality of the tinnitus can reflect the cause; for example, vascular causes may be pulsatile, clicking may be caused by spasm of muscles in the palate or ear.

Figure 1: Ear anatomy

Clinical features

Tinnitus occurs in 10-15% of adults and is disabling for 1-3% of the adult population. Tinnitus can be constant, intermittent, or occasional; it may also wax and wane. Tinnitus is associated with multiple causes, and the type of tinnitus helps to determine the cause of the tinnitus. The most common type of tinnitus is subjective, non-pulsatile and bilateral; this is the type most often associated with SNHL.

Tinnitus is considered to be chronic when it has persisted for at least six months. New onset tinnitus may resolve within that time period.

Tinnitus can be classified in several ways:

- Subjective versus objective

- Subjective tinnitus: perceived by the individual only, and cannot be heard by anyone else. This is by far the most common type of tinnitus.

- Objective tinnitus: not only heard by the individual, but may also be detected by others, usually requiring the use of a stethoscope. There usually are no other ear problems (HL, vertigo). This type occurs much less often (1.5%), and in most cases, the underlying cause can be determined.

- Etiology - primary versus secondary

- Primary/idiopathic tinnitus with no diagnosed underlying cause; may be associated with SNHL.

- Secondary tinnitus which is determined to be associated with a specific source and not associated with SNHL.

- Pulsatile versus non-pulsatile

- Pulsatile tinnitus is perceived as a rhythmic thumping or whooshing sound.

- Non-pulsatile tinnitus is generally continuous and while it may wax and wane, there is no rhythm to the perceived.

- Unilateral versus bilateral

- Unilateral tinnitus which only ever occurs in one ear.

- Bilateral tinnitus which can occur in both ears, but may occur occasionally in one ear only.

Individuals who experience tinnitus have provided many different descriptions of what the tinnitus sounds like to them. Descriptions include:

- high-pitched sound

- ringing sound

- whistle

- squealing sound

- steam

- wind

- rushing water

- roaring

- hum

- transformer hum

- television hum

- breathing sound (respiration)

- pulse-like sound.

Nocturnal tinnitus may result in symptoms of sleep disturbance or insomnia which are generally included in the entitlement and assessment of tinnitus. If a consequential entitlement for insomnia disorder is considered, consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

In the overall population, when comparing males and females, there are no differences in rates of occurrence of tinnitus.

Entitlement considerations

In this section

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment

Section A: Causes and/or aggravation

For VAC entitlement purposes, the following factors are accepted to cause or aggravate the conditions included in the Definition section of this entitlement eligibility guideline (EEG), and may be considered along with the evidence to assist in establishing a relationship to service. The factors have been determined based on a review of up-to-date scientific and medical literature, as well as evidence-based medical best practices. Factors other than those listed may be considered, however consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

The timelines cited below are for guidance purposes. Each case should be adjudicated on the evidence provided and its own merits.

Factors

- Being exposed to intermittent or continuous noise, other than acoustic trauma, that is of sufficient intensity and duration to cause HL greater than 25 decibels at 3000, 4000 or 6000 frequency (in the ear(s) with tinnitus), prior to clinical onset or aggravation.

- Exposure to at least one episode of acoustic trauma sufficient to have caused some decibel loss of sensorineural hearing (permanent or temporary) just prior to clinical onset or aggravation. The following exposures may result in acoustic trauma:

- fireworks

- loud music

- heavy machinery

- gunfire

- blast injury (i.e. exploding grenades, mines, or bombs).

Acoustic trauma is caused by short-term intense exposure to loud noise resulting in sudden damage to the hair cells of the organ of Corti, usually producing immediate symptoms of SNHL, pain (especially with loud noises) or tinnitus in the affected ear(s). The immediate symptoms, including sensorineural deafness, may abate over a few days.

- Exposure to at least one episode of aural trauma caused by noise just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus. Aural trauma caused by noise is caused by exposure to a blast resulting in sudden physical damage to any portion of the middle or inner ear. Aural trauma caused by noise can result in physical damage to the organ of Corti and this may cause tinnitus, usually associated with SNHL.

- Sustaining damage to the middle ear from inequalities in the barometric pressure (other than due to noise) on each side of the tympanic membrane (TM), known as otic (ear) barotrauma, within approximately 30 days prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus.

Ear barotrauma can occur when there is a difference in the air pressure between the middle ear and the external environment. It can present with ear pressure, pain, tinnitus and HL. Ear barotrauma is generally associated with eustachian tube dysfunction. Normally the air in the middle ear is absorbed into the mucosal lining and is continually replaced via the eustachian tube.

When the eustachian tube is blocked, the pressure in the middle ear decreases and the TM is retracted. The stretching of the TM can lead to bleeding or bruising in the TM, fluid in the middle ear, and occasionally TM rupture.

Less severe injuries, including most TM rupture, generally heal with time.

More severe injuries can involve the structures of the middle ear and may lead to a perilymphatic fistula. A perilymphatic fistula occurs most commonly when the thin membranes at either the oval or round windows are disturbed by trauma, resulting in a leak of fluid from the labyrinth into the middle ear. Perilymphatic fistulas can cause symptoms of dizziness, SNHL and tinnitus.

The following exposures may result in ear barotrauma:

- flying

- sky diving

- underwater diving

- working in a submarine

- being treated in a hyperbaric or hypobaric oxygen chamber

- slap to the outer ear.

- Having a moderate or severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus. It is important for timelines to be established.

Note: If considering entitlement for chronic tinnitus due to mild TBI, consultation with a disability consultant or a medical advisor is recommended.

- Having a head injury with temporal bone fracture within a few weeks of clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus. Transverse fractures of the temporal bone may cause injury to the cochleovestibular nerve resulting in tinnitus.

Fractures of the temporal bone may also result in tinnitus as a result of ossicular chain injuries.

- Using medication from the specified list of medications below during or just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus. In the majority of cases, some SNHL of greater than 25 decibels at 3000, 4000 or 6000 frequency occurs at the same time.

- parenteral aminoglycoside antibiotic:

- gentamicin

- streptomycin

- kanamycin

- amikacin

- netilmicin

- tobramycin

- intravenous administration of:

- ethacrynic acid

- furosemide

- bumetanide

- vancomycin

- erythromycin

- chemotherapeutic agents:

- nitrogen mustard

- bleomycin

- cisplatin

- a-difluoromethylornithine

- vincristine

- vinblastine

- misonidazole

- 6-amino nicotinamide

- carboplatin

- salicylates

- quinine.

Note:

- Individual medications may belong to a class of medications. The effects of a specific medication may vary from the class. The effects of the specific medication should be considered.

- If it is claimed a medication resulted in the clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus, the following must be established:

- The medication was prescribed to treat an entitled condition.

- The individual was receiving the medication at the time of the clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus.

- The current medical literature supports the medication can result in the clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus.

- The medication use is long-term, ongoing, and cannot reasonably be replaced with another medication or the medication is known to have enduring effects after discontinuation.

- parenteral aminoglycoside antibiotic:

- Having otosclerosis at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus. Otosclerosis is a primary disorder of the labyrinthine capsule characterized by new bone formation and often involving the footplate of the stapes. Otosclerosis itself, or surgery for the condition, can cause tinnitus.

- Having tuberculosis involving the temporal bone on the affected side of the head prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus

- Having Paget’s disease of bone affecting the skull at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus. Also known as osteitis deformans, it is a disease of bone marked by repeated episodes of bone resorption and new bone formation resulting in weakened deformed bones of increased mass.

- Having chronic eustachian tube disorder during or just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus.

Eustachian tube disorder causes include, but are not limited to:

- eustachian tube obstruction from any cause

- chronic rhinosinusitis with obstruction

- adenoid pathology

- chronic allergic disorders.

- Having chronic tympanic membrane disease during or just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus. TM diseases would include, but are not limited to TM perforation with or without surgery.

- Having chronic middle ear disease during or just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus. Middle ear disease would include, but is not limited to:

- chronic otitis media

- cholesteatoma, a cyst like growth originating in the middle ear, with erosion into the semicircular canal

- ossicular chain discontinuity due to infection, surgery, or trauma

- TM surgery with complications.

- Having an acute infection from a virus listed below within approximately 30 days prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus associated with SNHL. This is generally sudden SNHL (SSNHL), with HL developing rapidly in less than 72 hours.

The viruses include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Lassa virus

- mumps virus

- measles virus

- pertussis virus

- varicella-zoster virus.

- Having perilymphatic leaks from head injury, head trauma or barotrauma during or just prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus.

- Having at least one source of vascular sound, an abnormal sound generated by the turbulent flow of blood in an artery due to either an area of partial obstruction or a high rate of blood flow, in and around the affected ear prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus.

- Having an autoimmune disease with associated SNHL of greater than 25 decibels at 3000, 4000 or 6000 frequency in the ear(s) with tinnitus, prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus.

An immune disease would include, but is not limited to:

- systemic lupus erythematosis

- rheumatoid disease

- polyarteritis nodosa

- systemic sclerosis/scleroderma

- dermatomyositis

- Cogan’s syndrome.

- Having an intracranial neoplasm prior to clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus.

- Having specific complications of neurological disease at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus; this would include, but is not limited to:

- trigeminal neuralgia with associated stapedius muscle spasm

- myoclonus of the middle ear or palatal muscles

- multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases, usually with SNHL

- cerebral anoxia - due to ischemic changes in the auditory cortex

- raised intracranial pressure

- pseudotumor Cerebri – can cause pulsatile tinnitus.

- Having Meniere’s disease (MD) at the time of clinical onset or aggravation of tinnitus.

Note: Where entitlement is granted for MD, tinnitus is included in the entitlement and assessment of this condition.

- Inability to obtain appropriate clinical management of tinnitus.

Section B: Medical conditions which are to be included in entitlement/assessment

Section B provides a list of diagnosed medical conditions which are considered for VAC purposes to be included in the entitlement and assessment of tinnitus.

- Hyperacusis

Section C: Common medical conditions which may result, in whole or in part, from tinnitus and/or its treatment

No consequential medical conditions were identified at the time of the publication of this EEG. If the merits of the case and medical evidence indicate that a possible consequential relationship may exist, consultation with a disability consultant or medical advisor is recommended.

Appendix A: ASA to ISO-ANSI conversion

It is important to note the literature indicates American audiometric data collected prior to 1969/1970 may be based on the ASA standard. As late as 1977 it was recommended audiogram blanks be labelled as ISO or ANSI to ensure all hearing levels in a report were actually ISO or ANSI (Hearing and Deafness, 4th ed., p. 287).

Links

Related VAC guidance and policy:

- Chronic Otitis Media – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Hearing Loss - Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Meniere’s disease – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Otosclerosis - Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Paget's Disease of Bone (Osteitis Deformans) - Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Rheumatoid Arthritis – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Traumatic Brain Injury – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Vertiginous Disorders – Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

- Hearing Loss and Tinnitus - Policies

- Pain and Suffering Compensation – Policies

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police Disability Pension Claims – Policies

- Dual Entitlement – Disability Benefits – Policies

- Establishing the Existence of a Disability – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Peacetime Military Service – The Compensation Principle – Policies

- Disability Benefits in Respect of Wartime and Special Duty Service – The Insurance Principle – Policies

- Disability Resulting from a Non-Service Related Injury or Disease – Policies

- Consequential Disability – Policies

- Benefit of Doubt – Policies

References as of 22 January 2025

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2001). Statement of Principles concerning tinnitus (Reasonable Hypothesis) (No. 25 of 2001). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2001). Statement of Principles concerning tinnitus (Balance of Probabilities) (No.26 of 2001). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2020). Statement of Principles concerning tinnitus (Balance of Probabilities) (No. 85 of 2020). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Australian Government, Repatriation Medical Authority. (2020). Statement of Principles concerning tinnitus (Reasonable Hypothesis) (No. 84 of 2020). SOPs - Repatriation Medical Authority

Baguley, D. M. (2003). Hyperacusis. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96(12), 582–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680309601203

Bhagrat, V., & Hogan, D. (2024). Clinical Overview—Tinnitus. Clinical Key.

Biswas, R., Genitsaridi, E., Trpchevska, N., Lugo, A., Schlee, W., Cederroth, C. R., Gallus, S., & Hall, D. A. (2023). Low Evidence for Tinnitus Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology: JARO, 24(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-022-00874-y

Blevins, N. (2022). Presbycusis. UpToDate, Inc.

Bousema, E. J., Koops, E. A., van Dijk, P., & Dijkstra, P. U. (2018). Association Between Subjective Tinnitus and Cervical Spine or Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review. Trends in Hearing, 22, 233121651880064. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216518800640

Buergers, R., Kleinjung, T., Behr, M., & Vielsmeier, V. (2014). Is there a link between tinnitus and temporomandibular disorders? The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 111(3), 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.10.001

Canale, S. T., & Campbell, W. C. (1998). Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. Mosby.

Choi, J., Lee, C. H., & Kim, S. Y. (2021). Association of Tinnitus with Depression in a Normal Hearing Population. Medicina, 57(2), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57020114

Dalrymple, S. N., Lewis, S. H., & Philman, S. (2021). Tinnitus: Diagnosis and management. American Family Physician, 103(11), 663–671.

Davis, H., & Silverman, S. R. (Eds.). (1978). Hearing and Deafness (4th edition). Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Dee, R., Mango, E., & Hurst, L. C. (1988). Principles of Orthopaedic Practice. McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Dinces, E. (2023). Etiology and diagnosis of tinnitus. UpToDate, Inc.

Doege, T. (1993). Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment (4th ed.). American Medical Association: Chicago.

Fauci, A., Braunwald, E., Isselbacher, K., Wilson, J., Martin, J., Kasper, D., Hauser, S., & Longo, D. (1998). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 14th Edition. 36(9), 665–665.

Hanna, B. (2022). Tinnitus. DynaMed. EBSCO Information Services.

Hanna, B. (2023). Hyperacusis. DynaMed. EBSCO Information Services.

Hanna, B. (2024). Presbycusis. DynaMed. EBSCO Information Services.

Henry, J. A., Hollingsworth, D., Khan, F. A., Mitchell, S., Monfared, A., Newman, C. W., Omole, F. S., Phillips, C. D., Robinson, S. K., … Whamond, E. J. (2014). Clinical Practice Guideline: Tinnitus. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 151(S2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599814545325

Jafari, Z., Kolb, B. E., & Mohajerani, M. H. (2022). Hearing Loss, Tinnitus, and Dizziness in COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques, 49(2), 184–195. https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2021.63

Jarach, C. M., Lugo, A., Scala, M., van den Brandt, P. A., Cederroth, C. R., Odone, A., Garavello, W., Schlee, W., Langguth, B., & Gallus, S. (2022). Global Prevalence and Incidence of Tinnitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurology, 79(9), 888. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2189

Karacay, B. C., & Korkmaz, M. D. (2023). Investigation of Factors Associated with Dizziness, Tinnitus, and Ear Fullness in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders. Journal of Oral & Facial Pain and Headache, 37(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.11607/ofph.3286

Matheson, E. M., Fermo, J. D., & Blackwelder, R. S. (2023). Temporomandibular Disorders: Rapid Evidence Review. American Family Physician, 107(1), 52–58.

McCormack, A., Edmondson-Jones, M., Somerset, S., & Hall, D. (2016). A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hearing Research, 337, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2016.05.009

Moring, J. C., Resick, P. A., Peterson, A. L., Husain, F. T., Esquivel, C., Young-McCaughan, S., Granato, E., Fox, P. T., & for the STRONG STAR Consortium. (2022). Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Alleviates Tinnitus-Related Distress Among Veterans: A Pilot Study. American Journal of Audiology, 31(4), 1293–1298. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_AJA-21-00241

Ozdemir, O. (2022). Long-term effects of metal-on-metal Cobalt-Chromium-containing prostheses used in total knee arthroplasty on hearing and tinnitus. SiSli Etfal Hastanesi Tip Bulteni / The Medical Bulletin of Sisli Hospital. https://doi.org/10.14744/SEMB.2022.22587

Paparella, M. M., da Costa, S. S., & Fagan, J. (1991). Paparella’s Otolaryngology: Head & Neck Surgery: Two Volume Set (3rd ed.). Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers.

Reisinger, L., Schmidt, F., Benz, K., Vignali, L., Roesch, S., Kronbichler, M., & Weisz, N. (2023). Ageing as risk factor for tinnitus and its complex interplay with hearing loss—Evidence from online and NHANES data. BMC Medicine, 21(1), 283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02998-1

Ren, Y. F., & Isberg, A. (1995). Tinnitus in patients with temporomandibular joint internal derangement. Cranio: The Journal of Craniomandibular Practice, 13(2), 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/08869634.1995.11678048

Senior, S. L. (2019). Health needs of ex-military personnel in the UK: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 165(6), 410–415. https://doi.org/10.1136/jramc-2018-001101

Sereda, M., Xia, J., El Refaie, A., Hall, D. A., & Hoare, D. J. (2018). Sound therapy (using amplification devices and/or sound generators) for tinnitus. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12(12), CD013094. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013094.pub2

Tunkel, D. E., Bauer, C. A., Sun, G. H., Rosenfeld, R. M., Chandrasekhar, S. S., Cunningham, E. R., Archer, S. M., Blakley, B. W., Carter, J. M., Granieri, E. C., Henry, J. A., Hollingsworth, D., Khan, F. A., Mitchell, S., Monfared, A., Newman, C. W., Omole, F. S., Phillips, C. D., Robinson, S. K., … Whamond, E. J. (2014). Clinical Practice Guideline: Tinnitus. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 151(S2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599814545325

Veterans Affairs Canada (2024). Ear Anatomy [Image]. License purchased for use from Human Ear Anatomy. Ear Structure Diagram. The Human Ear Consists Of The Outer, Middle And Inner Ear. Royalty Free SVG, Cliparts, Vectors, and Stock Illustration. Image 180301021. (123rf.com)

World Health Organization. (2022). ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision). https://icd.who.int/

Zanon, A., Sorrentino, F., Franz, L., & Brotto, D. (2019). Gender-related hearing, balance and speech disorders: A review. Hearing, Balance and Communication, 17(3), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/21695717.2019.1615812